Find yourself prone to anxiety? The roots of the condition could stretch back to before you were even born, according to a new study in mice.

Researchers from Weill Cornell Medicine in the US have found that infection or stress in a mother during pregnancy could increase the risk of the offspring developing anxiety as an adult.

Studies have previously shown links between prenatal health problems and mental health issues later in life, including anxiety. In this latest investigation, researchers took a close look at potential neurological mechanisms that could be responsible.

Related: The Secret to Anxiety in Young Women's Brains May Have Been Found

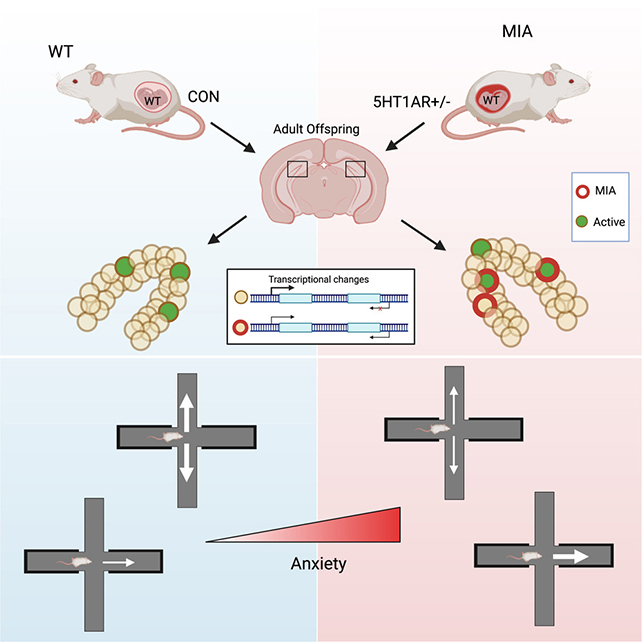

The research team genetically engineered mice in a way that simulates extra inflammation that a pregnant mother might experience under stressful conditions. Then, they carefully monitored the offspring produced.

The team focused on male offspring, who have more pronounced anxiety behaviors than females. These offspring were also genetically "normal", meaning they didn't inherit the predisposition for stress and inflammation from their mothers.

And yet, as adults, these offspring still showed telltale signs of anxiety, such as avoiding open spaces. What's more, scans indicated that a small number of brain cells in the ventral dentate gyrus (vDG), which helps assess potential threats in the surrounding environment, were working overtime when the animals felt threatened.

"Our data reveal prenatal adversity left lasting imprints on the neurons of the vDG, linking gestational environment to anxiety-like behavior," says neuropharmacologist Miklos Toth.

"This mechanism may help explain the persistent stress sensitivity and avoidance seen in some individuals with innate anxiety."

The researchers were also able to look at DNA methylation in the brains of the mice, a chemical tagging system that controls whether specific genes are turned on or off. These on-off switches were modified at thousands of sites along DNA strands collected from the vDG, especially in gene regions that control neuron communication.

When the mice felt they were under threat, it was in these reprogrammed areas where the neurons were working the hardest. It seems as though the mouse brains are coded to be more anxious about potential threats, and more eager to avoid them, even before the threat has actually appeared.

"Overall, these epigenetic changes are instructing certain neurons in the vDG to respond differently in adulthood when faced with unsafe environments," says neuropharmacologist Kristen Pleil.

"The neurons show too much activity, ultimately contributing to the mice perceiving the environment as more threatening than it actually is."

Anxiety is one of the more common mental health problems, and is thought to affect almost a third of us at some point during our lifetimes. Scientists are consistently making new discoveries about the different factors that increase the risk of anxiety, and how we might be able to better treat it.

Although only shown in mice so far, this new study hints at how the earliest stages of life could influence anxiety risk in adults, and may even feed into the development of diagnostic tests for the condition and perhaps even treatments.

It's also a reminder of how vital a healthy pregnancy is. The researchers are keen to continue their work by looking more closely at the mechanism they've uncovered, and why only a subset of neurons are affected by stresses in the womb.

"A mouse may have almost 400,000 cells in the vDG, but only a few thousand are impacted during pregnancy," says Toth. "Next, we really want to understand why these certain cells are epigenetically programmed."

The research has been published in Cell Reports.