HIV is infamous for its ability to hide in the human body for decades, typically requiring long-term treatment to prevent a rebound from dormancy.

In a new study, researchers shed light on where and how HIV lurks in these latent reservoirs, a key step in the quest to rid patients of the virus.

In its latent stage, HIV can persist in certain host cells as a dormant "provirus" – a viral genome that inserts itself into a host cell's DNA.

Related: HIV Cases Reach Lowest Point Since Rise of Disease in 1980s

That's a big reason why it's so hard to eradicate, even when tamed by modern treatments like antiretroviral drugs. These can suppress viral replication, reduce viral load, and stop disease progression, but they can't target hidden proviruses.

That means antiretroviral therapy can subdue but not eliminate HIV, forcing many patients to continue treatment indefinitely or risk a viral rebound.

Previous research shows HIV can linger in a variety of body tissues, including the brain, kidneys, liver, lungs, and gastrointestinal tract, among others.

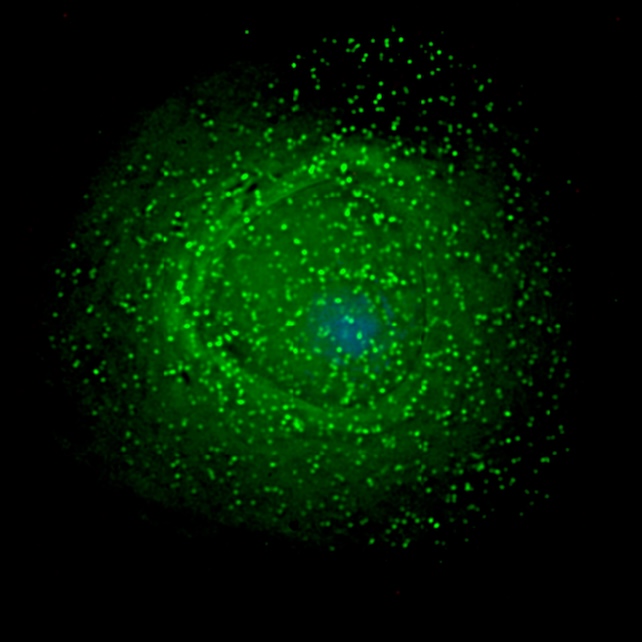

The immune system's T helper cells are the main latent reservoir, but not the only one. HIV also hides in skin cells, white blood cells, and organ-specific cells such as podocytes from the kidneys and support cells for neurons.

Many details of HIV latency remain poorly understood, including not just where the virus hides but also how it infiltrates diverse tissues and cell types and then settles in.

According to the new study, HIV achieves this with a tissue-specific approach, cloaking itself in a host cell's DNA by adjusting its behavior to fit the setting. In the brain, for example, it avoids genes and hides in less active regions of DNA.

"We found that HIV doesn't integrate randomly. Instead, it follows unique patterns in different tissues, possibly shaped by the local environment and immune responses," says microbiologist Stephen Barr from Western University in Ontario.

"This helps explain how HIV manages to persist in the body for decades, and why certain tissues may act as reservoirs of infection."

The study examined tissue samples from participants' blood, colon, esophagus, small intestine, and stomach, along with unmatched brain tissue.

The authors analyzed how often HIV integrated itself into specific parts of the host genome, then compared the patterns they observed across different body tissues from different people.

"Knowing where the virus hides in our genomes will help us identify ways to target those cells and tissues with targeted therapeutic approaches – either by eliminating these cells or 'silencing' the virus," says molecular virologist Guido van Marle from the University of Calgary.

The researchers discovered this using rare tissue samples collected from patients during the early years of the HIV/ AIDS pandemic, before modern treatments were available.

That allowed them to observe the virus in its natural state across multiple organs from the same individuals, revealing not only new details about HIV but also the scientific value of preserving historic samples.

"Our study is a powerful example of how we can learn from historic samples to better understand a virus that continues to affect tens of millions of people worldwide," Barr says.

These samples exist thanks to people who volunteered for HIV research early in the pandemic.

"Their willingness to contribute samples, at a time of stigma, fear, and with limited treatment options, was an act of bravery, foresight, and generosity that continues to advance scientific understanding of HIV and save lives today," van Marle says.

The study was published in Communications Medicine.