Neolithic people seem to have enjoyed chewing gum just as much as a bored kid in calculus. Their discarded wads are even revealing surprising details on human life as far back as 6,000 years ago.

Tar brewed from the bark of a birch tree is the world's oldest-known synthetic material. Neolithic communities in the European Alps used this malleable, tacky substance to attach handles to stone blades, repair pottery, and gnaw on while they worked.

"The precise reason for chewing tar remains unclear, but it has been suggested that it was chewed for medicinal purposes as it contains natural compounds with antimicrobial properties," write a team of archeologists led by Anna White from the University of Copenhagen.

Related: Scientists Reconstruct Entire Genome of a Woman From Her 5,700-Year-Old Chewing Gum

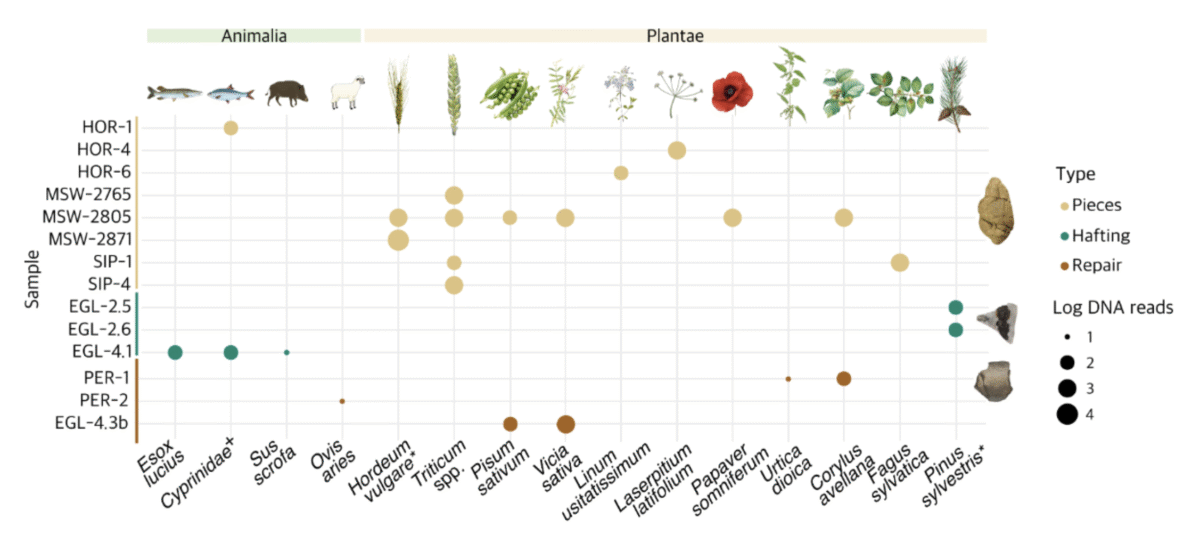

The team analyzed 30 birch tar artifacts from nine sites in the Alps region, most from lake settlements up to 6,300 years old. Twelve of these tar pieces were loose wads, many of which had telltale signs of chewing.

The great thing about adhesives is that they tend to collect all kinds of stuff from the environment, both accidentally and intentionally. Substances found in preserved tar – such as pine resin – may have been added deliberately to change the birch tar's material qualities.

Meanwhile, samples of the human oral microbiome become incidentally embedded in the tar when it is chewed, along with food or other materials from between the chewer's teeth. Some of the pieces contained DNA from linseed (Linum usitatissimum) and poppy seeds (Papaver somniferum), though it's unclear if the latter was eaten as food or for its opioid effects.

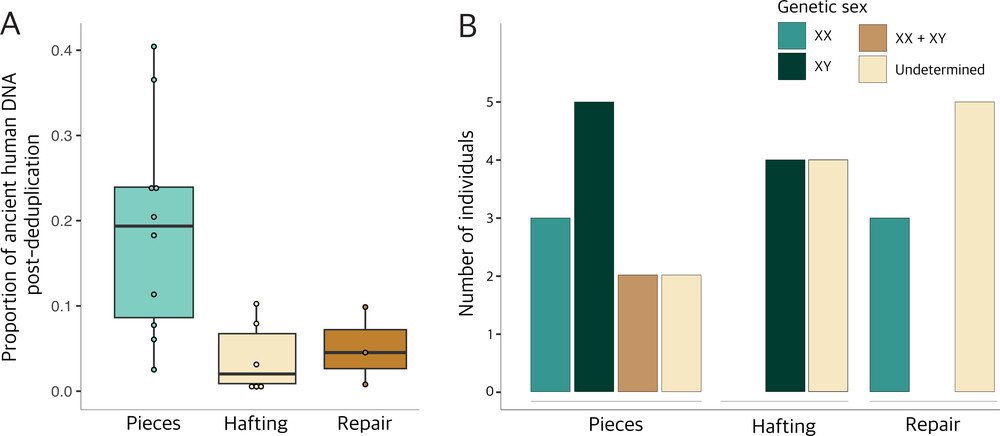

In 19 of the samples, ancient human DNA had been preserved with enough fidelity that, in some cases, the team was able to identify the sex of the person who had chewed it.

"The presence of human and oral microbial DNA in some of the samples suggests the tar was chewed, in some cases by multiple individuals," the authors write.

"The human DNA also enables us to determine the sex of those who chewed the tar, offering insights into gendered practices in the past, while plant and animal DNA shed light on past diets and the possible use of additives."

Analysis of the organic residue and ancient DNA trapped within the tar revealed male DNA in the 10 stone tools where the tar had been used as an adhesive, while female DNA was present in the tar used to repair all three items of pottery examined in the study.

It's possible that chewing was an important part of working with the tar as an adhesive material, since it hardens on cooling, and chewing would soften it.

But the addition of saliva tends to reduce the tar's adhesive properties, which only return after being reheated.

"[This] may explain why we find less oral microbial DNA in the hafted samples and the ceramic tars than in some of the 'chewed' pieces," the authors note.

Given that human remains from this era are scarce, the ancient chewing gum offers an unlikely route to better understanding our prehistory, which would otherwise be lost to time.

And dispose of your next piece of chewing gum wisely: it could end up preserving your DNA (and your dinner) for thousands of years.

This research was published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B.