Modifications to a type of immune cell programmed to recognize and kill cancerous tumors could make them even more effective assassins.

Researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Harvard Medical School have found a novel way to engineer chimeric antigen receptor natural killer (CAR-NK) cells to ensure they're not rejected by the body's immune system as foes rather than friends.

While the treatment is yet to be tested in humans, initial experiments in mice and human tissues in the lab suggest these new CAR-NK cells are well tolerated and effective at fighting cancer – a promising start for these next-gen upgrades.

Related: Cancer Vaccine Blocks Multiple Tumors in Mice For 250 Days

Natural killer cells are produced in the body as a first-line defense against cancers or tissues infected with viruses. They don't need priming, reacting to suspect cells that don't seem to belong. By engineering chimeric antigen receptors onto NK cells taken from a patient's own blood, the tiny killers can better target specific proteins known to identify cancerous cells.

The process of engineering enough CAR-NK cells to return to a patient takes several weeks, prompting scientists to consider using blood from healthy donors instead. While it means an army of CAR-NK cells can be ready to go at all times, the process increases the risk of immune system rejection.

Identifying specific immune cells that could potentially attack the treatment, researchers have made precise molecular changes that alter CAR-NK's surface proteins, effectively hiding the transplanted cells.

These modifications, together with carefully engineered boosts to the cancer-fighting capabilities of the cells, can be included on a single DNA piece called a construct, simplifying the process.

"This enables us to do one-step engineering of CAR-NK cells that can avoid rejection by host T cells and other immune cells," says biologist Jianzhu Chen, from MIT.

"And, they kill cancer cells better and they're safer."

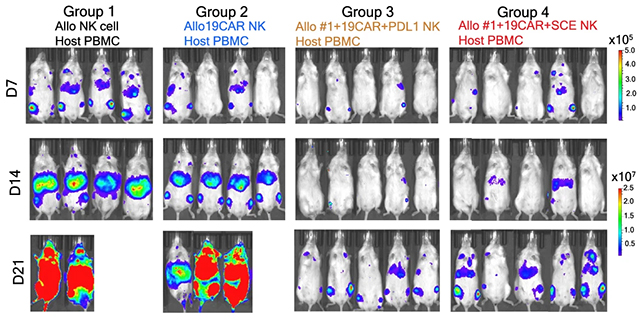

In mouse experiments, the differences between the tweaked CAR-NK cells and the standard versions were stark. The enhanced versions lasted at least three weeks, whereas the standard CAR-NK and NK cells were rejected by the immune systems of the mice, leaving the cancer to grow.

There was another benefit of the upgraded CAR-NK cells: a reduced likelihood of cytokine release syndrome – a potentially fatal side effect where the immune system triggers severe inflammation.

The study team thinks their approach may also improve CAR-T cell therapies, which use 'T' immune cells instead of natural killer cells. These therapies work well in some patients, but not in others.

One of the key next steps here will be clinical trials, so the researchers can see if these positive effects are seen in people as well. If those trials go well, there's plenty of potential for these allogeneic therapies (using immune cell fighters from healthy donors).

"We believe our approach could also be applied to other allogeneic cell-based products and can aid the design of 'off-the-shelf' allogeneic therapies," write the researchers in their published paper.

The research has been published in Nature Communications.