A cave straddling the border of Greece and Albania has just yielded an absolute treasure trove of spiders.

There, in the depths of Sulfur Cave, a team of scientists has discovered what they think might be the largest known spider web in the world – a shimmering silken sheet spanning a surface area more than 100 square meters (1,077 square feet).

Within that pearlescent palace reside more than 100,000 spiders of two different species: 69,000 individuals of Tegenaria domestica, the barn funnel weaver, and 42,000 individuals of Prinerigone vagans, the sheetweb spider.

It's the first documented case of true colonial web formation in both of these species, says a team led by arachnologist István Urák of Sapientia Hungarian University of Transylvania.

Not only do they have unique behaviors, the cave-dwelling spiders have genetic differences from their surface-dwelling kin, suggesting they are adapting to their isolated habitat.

Related: Scientists Translated a Spiderweb Into Music, And It's Eerily Captivating

"Our findings," the researchers write, "unveil a unique case of facultative coloniality in this cosmopolitan spider, likely driven by resource abundance in a chemoautotrophic cave, and provide new insights into the adaptation and trophic integration of surface species in sulfidic subterranean habitats."

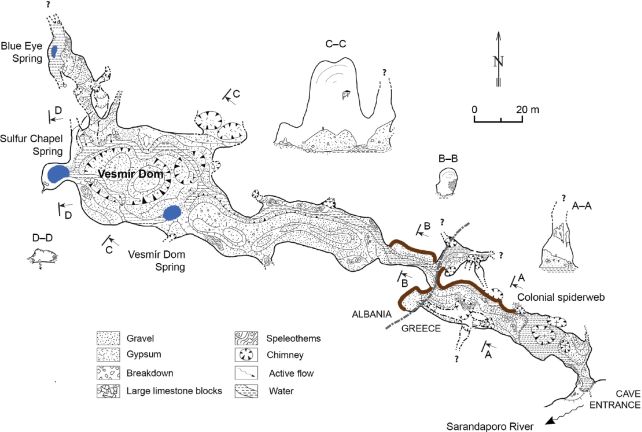

Sulfur Cave is a subterranean network of interconnected limestone chambers, with the entrance in Greece, and the body of the cave crossing the border into Albania. The spider megacity was first spotted in 2022 by recreational cavers, who alerted scientists after stumbling across the strange silken expanse.

Subsequently, scientists made several visits to the cave to understand its highly unusual habitat. It's not just the size – massive cave walls coated with webs – but the cohabitation: Although both spiders are quite common, neither had ever been seen living colonially, let alone peacefully alongside each other.

The vast sheet, the researchers ascertained, consists of thousands of individual funnel-shaped webs, overlapping and interconnected.

Genetic, microbiome, and isotope analyses revealed distinct cave-dwelling lineages isolated from their surface relatives and showing no signs of population exchange. Generations of isolation have reshaped both their genes and gut microbes. The colony appears to be completely cut off from the surface world.

Then the isotope analysis got to the meat of the matter – quite literally. The spiders were not eating insects that had somehow blundered into the cave, but insects that had been born there.

As the name suggests, Sulfur Cave is rich in sulfur, an element that supports an ecosystem based on sulfur-metabolizing microbes, out of reach of the life-giving light of the Sun that supports food webs based on photosynthesis.

In the cave, chemoautotrophic microbes congregate to feast upon the available chemicals, forming microbial mats. These microbial mats then attract predators such as centipedes, midges, isopods, beetles, springtails, and various arachnids.

The isopods and springtails eat the microbes; midges and spiders eat the isopods and springtails; and the spiders also feast, mightily, upon the abundant midge population. The most densely webbed sections of cave wall were those where midges were most numerous.

Spiders may not be everyone's idea of treasure, but scientifically, the cave is an utter marvel. It's a unique example of surface-dwelling spiders not only adapting to a chemoautotrophic cave ecosystem, but changing their social behavior to do so – and absolutely thriving.

Even in the darkest, most toxic corners of the planet, life finds a way. Sometimes, it even weaves a web.

The discovery has been published in Subterranean Biology.