A recent study points to a key bone-strengthening mechanism at work in the body, which could be targeted to treat the bone-weakening disease, osteoporosis.

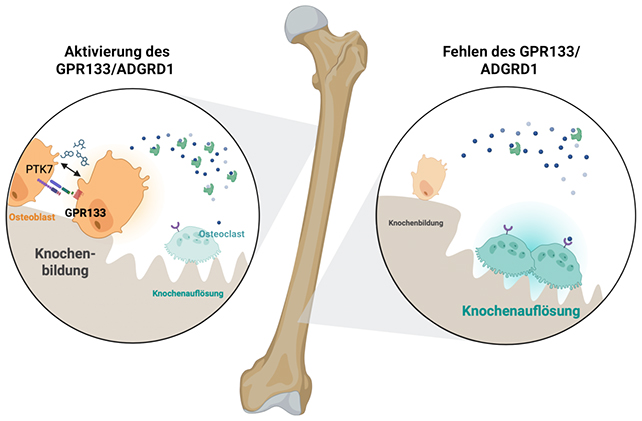

Led by researchers from the University of Leipzig in Germany and Shandong University in China, the study identified the cell receptor GPR133 (also known as ADGRD1) as being crucial to bone density, via bone-building cells called osteoblasts.

Variations in the GPR133 gene had previously been linked to bone density, leading scientists to turn their attention to the protein it encoded.

Related: Microplastics Found Deep Inside Human Bones, Scientists Warn

The team ran tests on mice in which the gene was either absent or could be activated using a chemical called AP503.

In the absence of the GPR133 gene, the mice grew up with weak bones, resembling the symptoms of osteoporosis. However, when the receptor was present and activated by AP503, bone production and strength improved.

Watch the video below for a summary of the findings:

"Using the substance AP503, which was only recently identified via a computer-assisted screen as a stimulator of GPR133, we were able to significantly increase bone strength in both healthy and osteoporotic mice," says University of Leipzig biochemist Ines Liebscher.

In these experiments, AP503 serves as a biological button that gets the osteoblasts working harder. The researchers were also able to show that it could work in tandem with exercise to strengthen bones even further.

Knowing that the GPR133 cell receptor is a crucial link in keeping mice bones strong is an important finding. While the results are based on an animal model, the underlying processes are likely similar in humans.

"If this receptor is impaired by genetic changes, mice show signs of loss of bone density at an early age – similar to osteoporosis in humans," says Liebscher.

Osteoporosis is a serious condition affecting millions worldwide. While available treatments can slow the condition's progress, there's no way to reverse or cure the condition.

Current treatments also tend to come with risky side effects (like an increased risk of other diseases) or become less effective over time.

There are actually numerous factors that have an influence on bone strength, and that gives scientists plenty of scope for finding methods that ward off issues like osteoporosis and promote a healthier old age.

In 2024, scientists developed a blood-based implant that supercharges this mechanism for bigger repair projects: broken bones. When skin tissue is wounded, our blood starts clotting as part of the healing process.

The international team of researchers behind the implant called it a "biocooperative regenerative" material: it uses synthetic peptides to improve the structure and function of the barrier naturally formed by blood when it clots.

In tests on rats, the gel-like substance – which can be 3D-printed – was effective in repairing bone damage. If this can be adapted and scaled up for human use, it has huge potential as a way of boosting the body's natural healing processes.

"The possibility to easily and safely turn people's blood into highly regenerative implants is really exciting," biomedical engineer Cosimo Ligorio, from the University of Nottingham in the UK, said when the 2024 study was published.

"Blood is practically free and can be easily obtained from patients in relatively high volumes."

Related: Back Pain Impacts 60% of Us – Here's How Your Curvy Spine Might Cause It

Scientists have long been interested in harnessing the body's natural repair processes to improve medical treatments – whether it's boosting the immune system, or enhancing natural materials with synthetic components.

Our bodies are actually incredibly clever when it comes to being able to patch up injuries and damage – but these repair processes can sometimes be overwhelmed, and they tend to become less effective as the wear and tear of aging takes its toll.

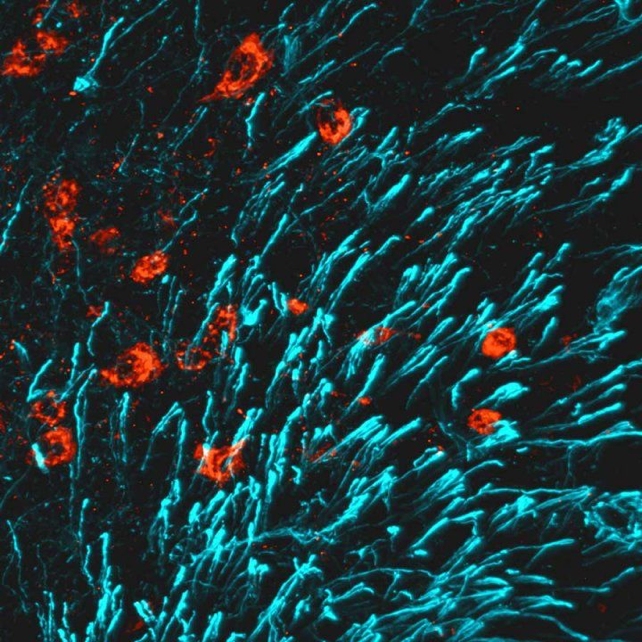

Another recent finding in this area of research was the discovery of a new hormone in female mice that promotes the growth of astonishingly strong and dense bones.

In a study published last year, a team led by researchers from the University of California, San Francisco identified a hormone called maternal brain hormone (MBH), which appears to boost bone density, mass, and strength in tests on both male and female mice.

"When we tested these bones, they turned out to be much stronger than usual," stem cell biologist Thomas Ambrosi from University of California Davis explained at the time the results were published.

"We've never been able to achieve this kind of mineralization and healing outcome with any other strategy."

While many of these breakthroughs have so far been demonstrated only in animals, and are yet to be tested in humans, the potential for future bone-strengthening medications looks very promising.

The authors of the 2025 study say future treatments could be used to strengthen bones that are already healthy, and build degraded bone back up to full strength, as in cases of osteoporosis in women who are going through menopause.

"The newly demonstrated parallel strengthening of bone once again highlights the great potential this receptor holds for medical applications in an aging population," says molecular biologist Juliane Lehmann, from the University of Leipzig.

The research has been published in Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy.

An earlier version of this article was published in September 2025.