Ever experienced a moment of flow when working with another human to achieve a common goal, almost as if you and your collaborator are tuned in to each other's brains? You may have literally been 'in sync' on a neurological level, new research shows.

Humans are highly social creatures. We rely on collaboration for so many aspects of our lives, from communicating through speech and keeping a beat, to raising children and working. Teamwork, as they say, makes the dream work.

Collaboration requires following the same instructions and, to a certain extent, shared modes of thinking. And it turns out this is actually visible – within milliseconds – in measures of brain activity when a pair of people collaborate on a shared task.

Related: People's Brains Sync Up When Gaming Together, Even When Nobody's There

But it's difficult to tell if that synchronicity comes from the simple fact that they're both working on the same task, or if it's specifically because they're working together.

Cognitive neuroscientist Denise Moerel, of Western Sydney University in Australia, led a study that cleverly controls these entangled variables to see what's really going on.

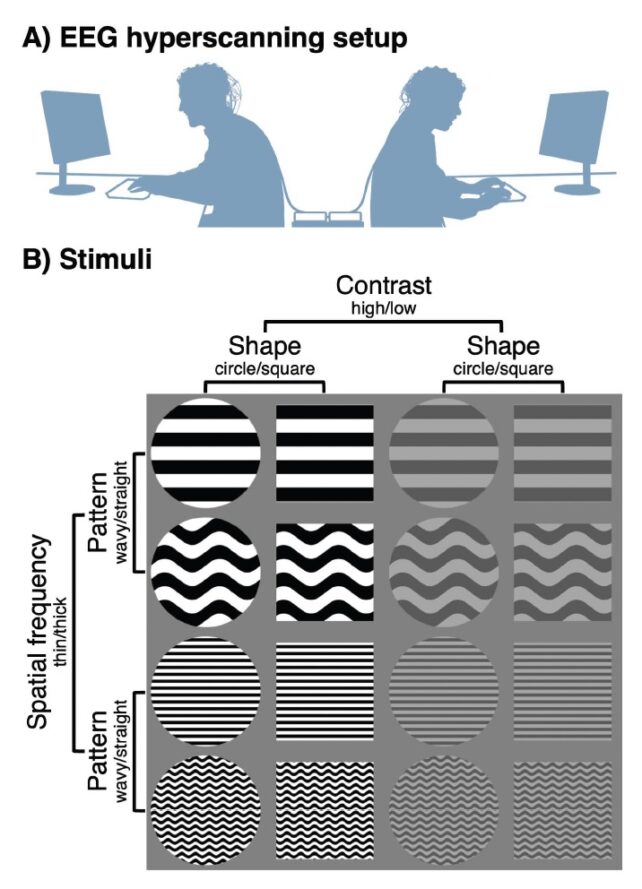

Participants were paired to form 24 teams. Each pair had to decide together how they would sort shapes with black-and-white patterns of varying contrast and pattern size that appeared on a computer screen.

They had to sort these shapes into four groups of four, which meant choosing two features (round or square shape, wavy or straight pattern, high or low contrast, and small or big pattern) as the basis for categorization.

The two teammates were allowed to talk and work together during this phase, but once they had agreed on the 'rules', they proceeded back-to-back, with no talking allowed, each looking at a computer screen showing a shared workspace for sorting shapes. Occasionally, they were allowed to take breaks and chat.

During the back-to-back collaboration phase, electroencephalograms (EEGs) recorded their brain activity to track how much it aligned. But the researchers also compared EEG data between pairs, which is where things got really interesting.

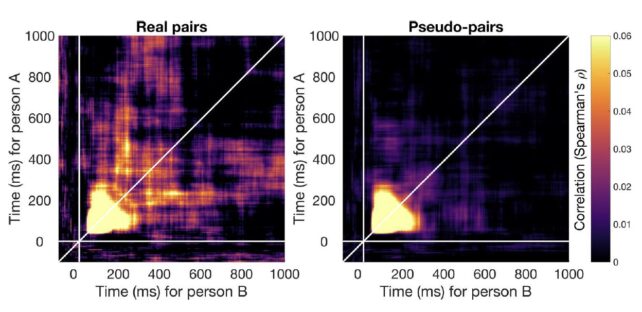

Within the first 45-180 milliseconds after a shape appeared, everyone in the experiment showed similar brain activity, all facing the same task.

But by 200 milliseconds, that diverged. Brain activity remained aligned within pairs, but not across the entire group. This alignment grew stronger as the experiment progressed, and pairs became more 'in sync' as teammates, with their shared rules reinforced throughout the experience.

This phenomenon was significantly higher in the data for real pairs, as opposed to randomly-matched pseudo-pairs that had not actually collaborated beforehand, but whose data were paired for the sake of comparison, because they had happened to follow similar rules.

For example, two different pairs might have both chosen to sort the shapes into circles or squares, and wiggly or straight patterns. But when the brain activity of one person from each pair was compared, their strengthening alignment was far weaker than their alignment with their real teammates.

These results mean that the strong alignment between real pairs' brain activity probably isn't due to the particular system they'd agreed to follow during the task alone. There was something about working with your collaborator, the person with whom you had formed the system, that specifically made a difference.

"The results highlight that social interactions play a central role in shaping neural representations in the human brain," the authors report.

"[This method has] promising applications for understanding group collaboration, communication, and decision-making."

This research was published in PLOS Biology.