In an ancient rock shelter in the heart of Malawi, archaeologists have found the world's oldest evidence of a funeral pyre for an adult.

The charred remains, 9,500 years old, reveal that the deceased was a woman aged between 18 and 60 years old when she died, and that her body was carefully prepared for cremation on a large pyre that burned for many hours. This took place as part of a deliberate funerary ritual at a site that had already served as a place for death rites for at least 8,000 years.

It's "the earliest evidence for intentional cremation in Africa, the oldest in situ adult pyre in the world," writes a team led by anthropologist Jessica Cerezo-Román of the University of Oklahoma.

Related: Oldest Human Mummies Discovered, And They're Not What We Expected

The discovery deepens our understanding of hunter-gatherer funerals, showing that their rites could be far more complex than previously assumed.

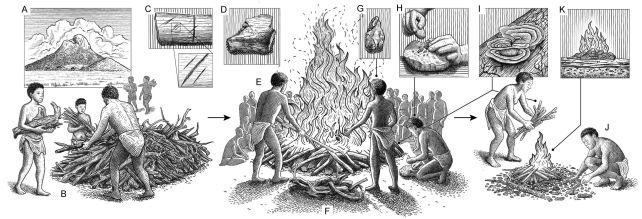

This ceremony involved planning and construction, as well as significant resource investment to gather and tend the large quantity of wood needed to keep the pyre burning for hours or longer.

The continuous use of the site also implies a shared social memory, and possibly even forms of ancestor veneration once thought minimal among mobile foragers.

The gravitas with which humans approach death has been present for many millennia, with the earliest known intentional burial dating back 78,000 years. Earlier evidence of intentional burials, possibly by other hominin species, is still hotly contested.

As for cremation, evidence is scarce before about 7,000 years ago, especially among hunter-gatherer cultures. The earliest cremated human remains, found buried at Lake Mungo in Australia, date back to around 40,000 years ago, yet no pyre was found.

The earliest confirmed in situ pyre (where remains are found where the cremation took place, on a specially built fire) dates back to 11,500 years ago in what is now Alaska, a funerary rite for a small child.

After that, no evidence of pyre cremation appears until about 7,000 years ago at Beisamoun in the southern Levant.

At the base of Mount Hora in Malawi is an archaeological site known as HOR-1 where humans were active for an estimated 21,000 years. Between 16,000 and 8,000 years ago, it was used for mortuary practices. Archaeologists have identified the remains of at least 11 individuals there.

Only one individual shows evidence of cremation before burial. Her official designation is Hora 3, and although only parts of her skeleton were recovered – limb bones, parts of her vertebrae and pelvis, and some phalanges – those parts, and the large deposit of ashy residue in which they were found, paint a vivid picture of her funerary rites.

The burning and cracking of the bones indicate they were exposed to high temperatures for a long time. Moreover, cut marks on the bones show that some parts of Hora 3's body were disarticulated before the cremation.

Color patterns on the bones also show that they were moved during cremation, perhaps as the fire was stoked and stirred.

No part of the woman's skull or any teeth were found, suggesting that her head may have been removed before the burning. This practice, evidence of which has been found at other archaeological sites in the region, is likely "related to mortuary practices associated with remembrance, social memory, and ancestral veneration, which involved the posthumous manipulation and curation of body parts," the researchers write in their published paper.

Meanwhile, the extent and contents of the ash deposit are consistent with a pyre consisting of at least 30 kilograms (66 pounds) of deadwood, grass, and leaves – a considerable amount of gathered resources that would have created a long-lasting fire.

Ash deposits layered over the remains also suggest the same spot was used for fires for several hundred years after the cremation.

The researchers take this to mean the site was likely what archaeologists call a "persistent place" that may have been tied to territory and reflects ancestral connections in what remains to this day a monumental landscape.

"The history of large fire construction at that location in the site, the maintenance associated with the cremation event, and the subsequent large burning events reflect a deep-rooted tradition of repeatedly using and revisiting the site, intricately linked to memory-making and the establishment of a 'persistent place'," they write.

"These practices emphasize complex mortuary and ritual activities with origins predating the advent of food production, and challenge traditional assumptions about community-scale cooperation and place-making in tropical hunter-gatherer societies."

The research has been published in Science Advances.