A study in mice by researchers from Stanford University has traced the loss of cartilage that comes with aging to a single protein, pointing to treatments that may one day restore mobility and ease discomfort in seniors.

The protein 15-PGDH has previously been extensively linked to aging: it becomes more abundant as we get older, and interferes with the molecules that repair tissue and reduce inflammation.

That led scientists to consider whether 15-PGDH might be involved in osteoarthritis, where stress on joints leads to the breakdown of collagen in cartilage, causing inflammation and pain.

Related: The Best Medicine For Joint Pain Isn't What You Think, Says Expert

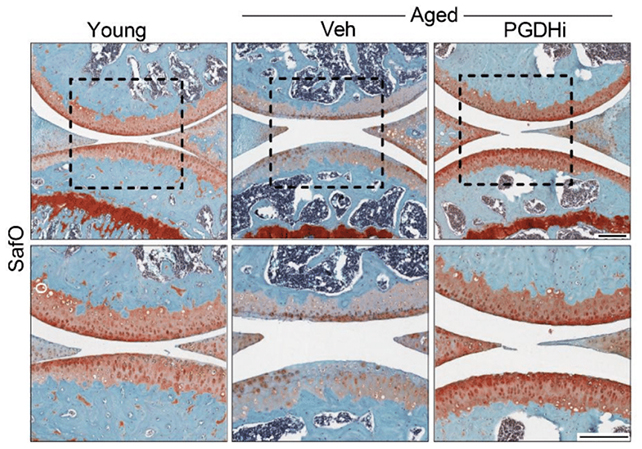

In tests on old mice, knee cartilage that had previously worn down thickened following the introduction of a 15-PGDH inhibitor. In similar tests on young, injured mice, the inhibitor offered protection against the usual effects of injury-induced osteoarthritis.

When the researchers triggered the equivalent of an anterior cruciate ligament injury in mice and subsequently applied the treatment, osteoarthritis didn't develop, as would normally be expected in these kinds of mouse models.

Previous attempts at cartilage regeneration included the use of stem cells, a factor that was no longer necessary when 15-PGDH was inhibited. Instead, the chondrocyte cells that make and maintain cartilage were being transformed into a healthier, more useful state.

"This is a new way of regenerating adult tissue, and it has significant clinical promise for treating arthritis due to aging or injury," says microbiologist Helen Blau. "We were looking for stem cells, but they are clearly not involved. It's very exciting."

Treated mice had a steadier gait, suggesting they were experiencing less pain, and were shown putting more weight on their injured legs – signs that the cartilage restoration equated improved physical health.

The same experiment was also tried on human tissue samples taken from people having knee replacement surgery. Again, there were clear signs of regeneration, with the cartilage getting stiffer and showing fewer signs of inflammation.

"The mechanism is quite striking and really shifted our perspective about how tissue regeneration can occur," says orthopaedic scientist Nidhi Bhutani. "It's clear that a large pool of already existing cells in cartilage are changing their gene expression patterns."

"And by targeting these cells for regeneration, we may have an opportunity to have a bigger overall impact clinically."

While there's still plenty of work to do, this could eventually lead to effective treatments to roll back the damage done by arthritis or aging in general. We could be heading towards a future where hip and knee replacements are no longer needed.

Besides replacing the joints affected, current treatment options for osteoarthritis are limited to pain management. Despite promising research in recent years, we don't have anything yet that tackles the root cause of the condition.

Related: Arthritis Affects Thousands of Kids, And One Piece of Advice Is Crucial

The next steps could include a clinical trial. A previous trial of a 15-PGDH blocker to combat muscle weakness didn't raise any red flags in terms of health and safety, which should speed up the process of trials for similar drugs.

"We are very excited about this potential breakthrough," says Blau. "Imagine regrowing existing cartilage and avoiding joint replacement."

The research has been published in Science.