A surprising new study has found that blocking reproduction in some mammals may increase their life expectancy by an average of 10 percent.

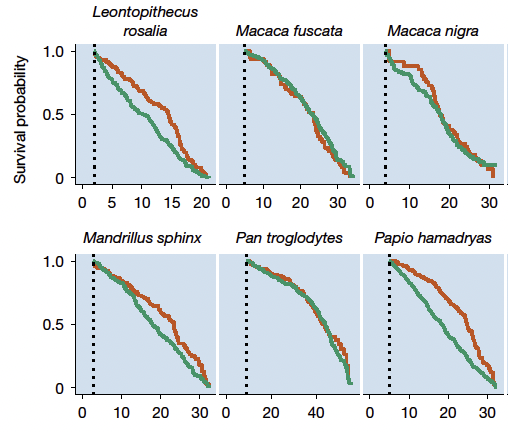

The research is primarily based on captive creatures kept in zoos and aquariums around the world, but it found that many animal groups, such as primates, marsupials, and rodents, experience a longevity boost when surgically sterilized or administered contraceptives.

Some species experienced a greater effect than others, and it depends on the sex of the animal, their environment, timing, and the procedure used.

Related: There's an Evolutionary Reason Why Female Mammals Live Longer

For instance, female hamadryas baboons (Papio hamadryas) on hormonal contraception lived 29 percent longer than their untreated counterparts, the study found. What's more, male hamadryas baboons that were castrated lived 19 percent longer.

"This study shows that the energetic costs of reproduction have measurable and sometimes considerable consequences for survival across mammals," says statistical and mathematical ecologist Fernando Colchero from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

"Reducing reproductive investment may allow more energy to be directed toward longevity."

The findings support a broad evolutionary theory of aging that pits reproduction against DNA repair and growth.

An animal can expend only so much energy in a lifetime, the theory goes, and offspring are a significant investment, diverting a large share of that limited resource away from growth and healing.

If an animal cannot reproduce because it lacks the necessary hormones or anatomical parts, it may theoretically become a healthier and stronger individual.

To test that idea, Colchero and colleagues analyzed the records of 117 mammal species with well-documented birth and death dates held in captivity worldwide.

The international team of researchers also conducted a meta-analysis of 71 published studies on sterilized animals, ranging from highly controlled lab experiments to studies in the wild. These studies were published between 1930 and 2021.

"The analysis of zoo records provides unparalleled insight into the taxonomic breadth of the lifespan response, with male castration, female surgical sterilization, and ongoing female hormonal contraception linked to increased life expectancy across a broad range of species within the mammalian kingdom," the study authors conclude.

Interestingly, the life-prolonging effects of sterilization were similar for both males and females. For male mammals housed in zoos, castration and similar forms of permanent surgical sterilization improved survival, but not vasectomies.

This suggests that lowering androgen levels may improve survival in some male animal groups, such as rodents, possibly because of reduced risky or aggressive behaviors.

In fact, the greatest longevity gains were observed among male mammals that underwent surgical sterilization early in life, even before puberty.

"This indicates that the effect stems from eliminating testosterone and its influence on core ageing pathways, particularly during early-life development. The largest benefits occur when castration happens early in life," says lead author Mike Garratt of the University of Otago in New Zealand.

In female mammals, meanwhile, several forms of sterilization were linked to longer lifespans and fewer infections. That is possibly because these methods reduce the physiological costs of pregnancy, lactation, and reproductive cycling – all of which can have an impact on how much energy is devoted to growth, repair, or immune defense.

Unlike captive male mammals, sterilization age didn't appear to affect longevity in females (though the data for this relationship were much weaker than for males).

"This supports arguments for the evolutionary benefits of menopause, where reduced later-life reproductive investment contributes to improved longevity, and this provides fitness benefits via kin selection," argue the study authors.

Whales, for instance, are one of the few animals like ourselves that go through menopause, and they live astonishingly long lives.

But living longer does not necessarily mean more healthy years.

While female rodents may live longer if they are sterilized, the authors of the current study found that later health may be impaired – a "health-survival paradox" also observed in post-menopausal women who "outlive men on average but suffer increased frailty and poorer overall health."

Extending the implications of these results to humans, however, is difficult because data are limited. Studies of historical records suggest that castrated men live, on average, 18 percent longer, though the accuracy of those records is debated.

Related: Human Penis Size Evolved For 2 Purposes, New Study Finds

For women, modern data on hysterectomies (the surgical removal of the uterus) and oophorectomies (the surgical removal of one or both ovaries) point to a very small effect size in the opposite direction.

The meta-analysis found a one percent reduction in survival among women who had undergone these procedures for benign conditions.

"Reproduction is inherently costly," Colchero, Garratt, and colleagues explain. "However, human environments – through healthcare, nutrition, and social support – can buffer or reshape these costs".

The zoo is a much more restricted and controlled setting that gives us an unprecedented glimpse into the wild ways of evolution.

The study was published in Nature.