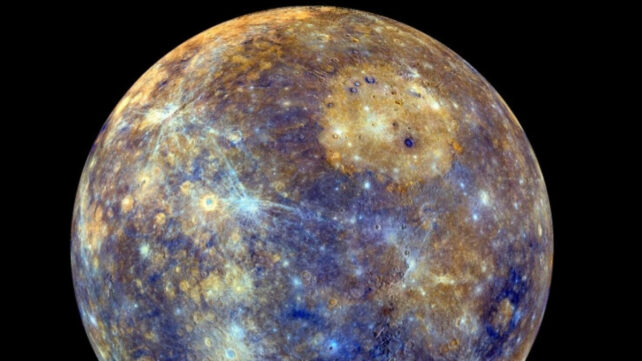

The smallest planet in our Solar System may be hiding a big secret.

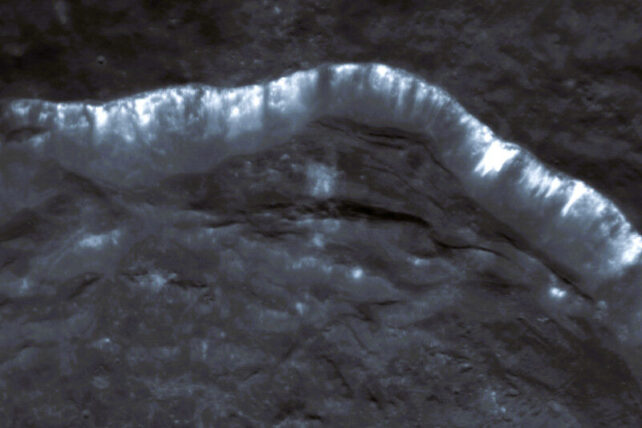

Curious bright streaks on Mercury's surface, doodled on its craters and slopes, are probably a sign of very recent geological activity, according to new models.

The findings suggest that Mercury is far from being 'dead' or dull, as astronomers once supposed.

Instead, our neighbor's 'hellscape' of a surface seems to be alive and kicking – geologically speaking, that is.

Related: A Fortune of Hidden Diamonds Could Be Concealed Inside Mercury

Until recently, scientists had catalogued only a handful of Mercury's bright streaks, known formally as lineae.

Now, astronomer Valentin Bickel from the University of Bern in Germany and his colleagues at the Astronomical Observatory of Padova in Italy have put together a survey covering 402 of them.

Reading between the bright lines, the team has painted a whole new portrait of Mercury – one that is surprisingly volatile for a little planet with no atmosphere that has had 4.5 billion years to cool off.

The researchers used machine learning to analyze 100,000 high-resolution images of the planet taken between 2011 and 2015.

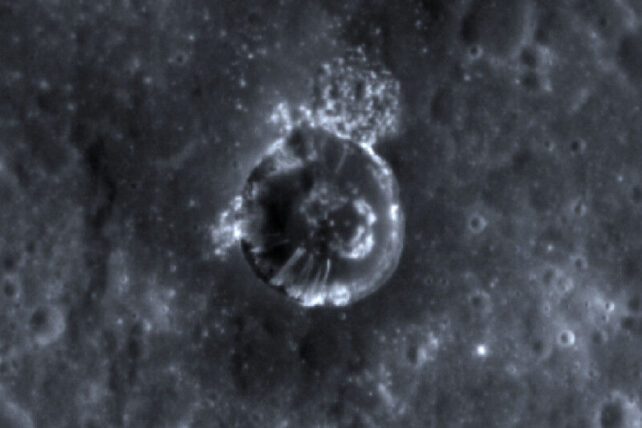

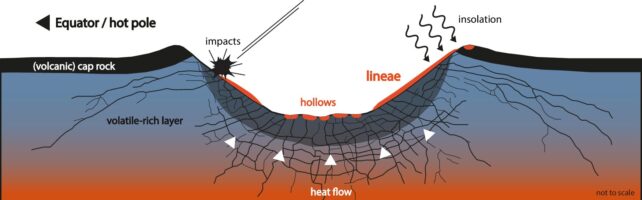

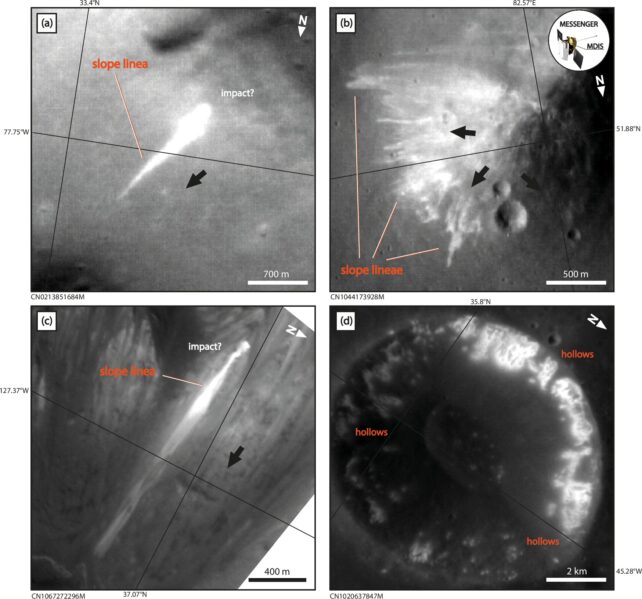

Their findings reveal that the long bright lines on Mercury's surface tend to cluster on the sun-facing slopes of its craters, although they don't always appear to emanate from hollows.

Lineae on other planets are thought to erode quickly, so the study authors suspect that the streaks are still forming and evolving on Mercury today. In other words, these aren't signs of a turbulent past but of a mercurial present, based on the flow of heat and volatile materials, like sulfur, from below the planet's surface.

"Volatile material could reach the surface from deeper layers through networks of cracks in the rock caused by the preceding impact," explains Bickel.

"Most of the streaks appear to originate from bright depressions, so-called 'hollows.' These hollows are probably also formed by the outgassing of volatile material and are usually located in the shallow interior or along the edges of large impact craters."

The team hopes to prove their hypothesis right using new images of Mercury from missions at the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA).

If Mercury's surface is still active, we should get a closer glimpse soon.

The study was published in Nature Communications Earth & Environment.