In a controversial study published in April last year, researchers described an astonishing phenomenon: a forest of Norway spruce trees (Picea abies) appeared to 'sync' their electrical signaling ahead of a partial solar eclipse.

Now there's a new theory about what was actually going on.

Having examined the data, ecologists Ariel Novoplansky and Hezi Yizhaq from Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Israel propose an explanation that's not quite as sensational.

Novoplansky and Yizhaq suggest that the electrical activity seen in the trees was caused by a temperature drop, a passing thunderstorm, and several local lightning strikes; factors that previous research has shown can trigger similar signaling responses in plants.

"To me, [the previous study] represents the encroachment of pseudoscience into the heart of biological research," says Novoplansky.

"Instead of considering simpler, well-documented environmental factors, like a heavy rainstorm and a cluster of nearby lightning strikes, the authors leaned into the more seductive idea that the trees were anticipating the impending solar eclipse."

In October 2022, a forest in the Dolomite mountains in northeastern Italy displayed what researchers described as "individual and collective bioelectrical responses to a solar eclipse", with older trees showing stronger signaling before and during the eclipse.

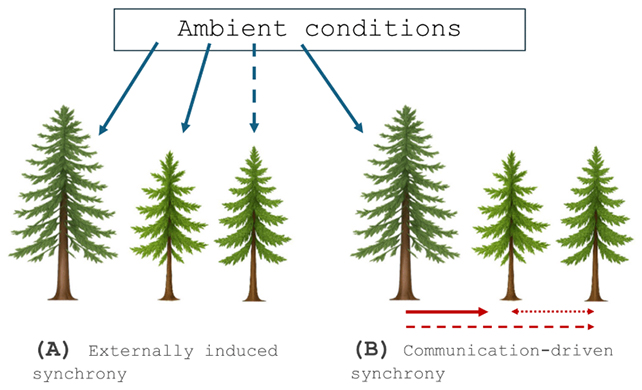

The activity, the researchers claimed, may have been a sign of the older trees' experience of previous events being passed on to the rest of the forest. In line with earlier studies, they proposed that the spruce trees were sensing an impending environmental change and coordinating a response. In this case, to a solar eclipse.

Not so, Novoplansky and Yizhaq argue in their new paper. They suggest the environmental change was far more likely to have been the thunderstorm, offering up several reasons why the original team of researchers reached the wrong conclusion.

First, solar eclipses are unique in their path, magnitude, and duration, so it would've been impossible for older trees to use 'remembered' knowledge to predict the next one.

Second, the gravitational variations that might have provided a heads-up would only have been very slight, roughly comparable to a new Moon.

What's more, there was no real need for the trees to coordinate a response to the solar eclipse. It was only a partial eclipse, with the reduction in light comparable to that on a cloudy day, so there wouldn't have been any major disruptions to photosynthesis or other processes.

"The eclipse only reduced light by about 10.5 percent for two short hours, during which the level of sunlight was approximately twice what the trees could practically use," says Novoplansky.

"Frequent fluctuations in cloud cover at the study location change light quality and quantity by much bigger amplitudes."

The researchers point out that the original study only analyzed three trees and five stumps, so it was hardly a thorough data sweep of the forest. Measurements in the initial study were more likely the result of individual trees responding to lightning rather than the forest collaborating as a collective, argue Novoplansky and Yizhaq.

Plants have been known to 'anticipate' environmental changes in the past, such as bracing for drought if there are early signs of it in the soil, so the idea that a forest could anticipate a solar eclipse isn't completely without precedent.

Related: Giant Stick Insect Found Hiding in Rainforest May Be Australia's Heaviest

However, the idea fails on several levels, as Novoplansky and Yizhaq point out.

The work to investigate tree electromes (the charged molecules passing through their cells) continues, and while there's controversy around this particular patch of forest, there is no doubt that more exciting discoveries are to come in this field.

"The electrical activity of trees is a real phenomenon, but it's still a nascent field of inquiry," says Novoplansky. "The idea that variations in electrical signals, observable even in dead logs, might encode memory, anticipation, or collective responsiveness requires a few extraordinary leaps, none of which were supported in the study."

"The forest is wondrous enough without inventing irrational yet superficially fantastic claims of anticipatory responsiveness or communication based only on correlation."

The research has been published in Trends in Plant Science.