Scientists have taken a major step toward treating spinal cord injuries that cause paralysis.

In lab dishes, researchers at Northwestern University grew tiny organoids of the human spinal cord. Then, they injured the samples and administered a treatment that helped the tissue repair and regenerate.

"We decided to develop two different injury models in a human spinal cord organoid and test our therapy to see if the results resembled what we previously saw in the animal model," biomedical engineer Samuel Stupp says.

"After applying our therapy, the glial scar faded significantly to become barely detectable, and we saw neurites growing, resembling the axon regeneration we saw in animals. This is validation that our therapy has a good chance of working in humans."

Spinal cord injuries often lead to paralysis because damaged nerve cells in the central nervous system regenerate poorly. This is partly due to suppression mechanisms that impede the growth of new axons and the emergence of scar tissue that is difficult for nerve fibers to penetrate.

In previous work, Stupp and his team developed a material called IKVAV-PA that they used to reverse paralysis in mice with severe spinal cord injury. The key to this treatment is supramolecular therapeutic peptides – nicknamed 'dancing' molecules – that can match the motion of the receptors on nerve cells to coax axon regrowth.

"Given that cells themselves and their receptors are in constant motion, you can imagine that molecules moving more rapidly would encounter these receptors more often," Stupp explained in 2021. "If the molecules are sluggish and not as 'social,' they may never come into contact with the cells."

Mouse models are important, but they are only an early step. Although these tiny animals can offer a reasonable laboratory to explore a potential treatment, the next logical move is to test it in human tissue – not in living people, where something could go wrong, but in cultured blobs grown from stem cells.

"One of the most exciting aspects of organoids is that we can use them to test new therapies in human tissue," Stupp says. "Short of a clinical trial, it's the only way you can achieve this objective."

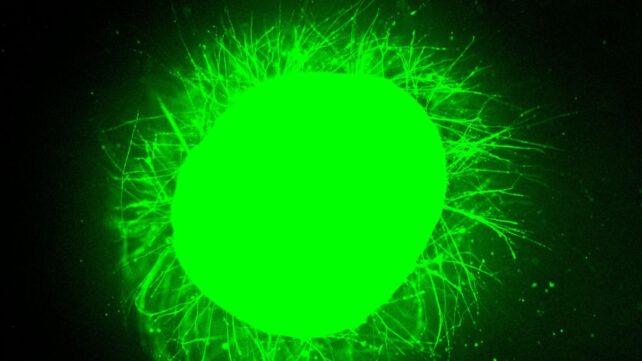

So, this is what the researchers did. Using induced pluripotent stem cells from an adult donor, they grew 3-millimeter-wide spinal cord organoids and cultured them for several months. During this time, the organoids developed much of the cellular architecture of a human spinal cord, including neurons, astrocytes, and organized tissue layers.

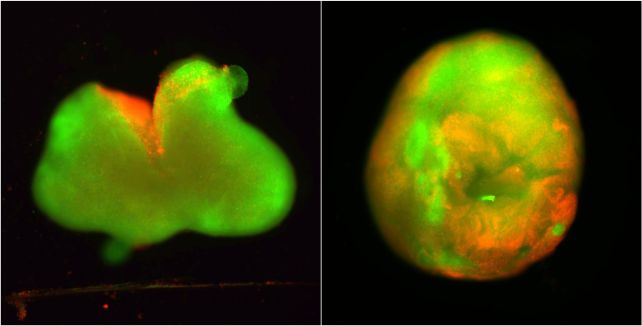

Once the organoids were mature enough, some were cut with a scalpel, while others received a compression injury similar to the crushing trauma that can occur in a car crash. Both types of injury can result in paralysis.

In every case, the organoids underwent immediate nerve cell death, the growth of glial scars that form around damage in the central nervous system, and inflammation, similar to the response seen in real spinal cord injuries.

"We could distinguish between the astrocytes that are a part of normal tissue and the astrocytes in the glial scar, which are large and very densely packed," Stupp says. "We also detected the production of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans, which are molecules in the nervous system that respond to injury and disease."

Related: Scientists Grew Stem Cell 'Mini Brains' And Then The Brains Sort-of Developed Eyes

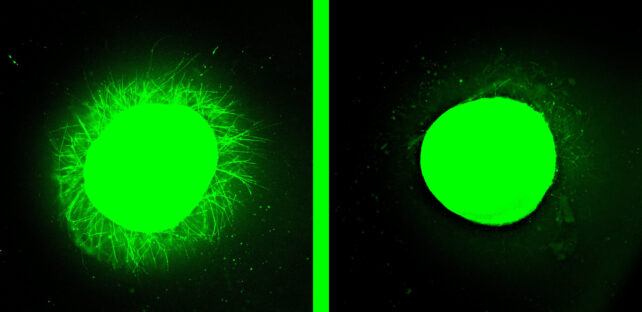

Next, the IKVAV-PA liquid was applied to some injuries, while others were treated with a control that did not contain the dancing molecules. For the injuries receiving treatment, the liquid immediately gelled into a scaffold, while the active molecules chemically and physically encouraged nerve cells to regrow.

The difference was striking. The treated organoids showed significantly less inflammation and scarring than the control group, and significantly more nerve cell regrowth.

It's still likely years away from being ready for testing in humans, but the consistent results across both mouse and human tissue models are highly promising for the development of future therapeutics.

The research has been published in Nature Biomedical Engineering.