Across the Milky Way there are vacant spaces where a star once brightly shone. Some left clues in a dramatic death, or faded into retirement. Others simply moved into a new neighbourhood.

Not all vacancies have such convenient explanations, though. Some were there one moment and gone the next, inviting speculation over rare types of star death, extreme astrophysics, and, of course… advanced alien technology.

By comparing star catalogues dating back to the 1950s with more recent datasets, researchers with the Vanishing & Appearing Sources during a Century of Observations project have identified around 100 bright dots that seem to have vanished without a trace.

The search is an ongoing one for lead researcher Beatriz Villarroel and her colleagues, one that started several years ago as part of a hunt for potential signs of alien intelligence.

"Finding an actually vanishing star – or a star that appears out of nowhere! – would be a precious discovery and certainly would include new astrophysics beyond the one we know of today," says Villarroel, a theoretical physicist from Stockholm University.

In an earlier study Villarroel and her team compared the positions of some 10 million objects recorded in the US Naval Observatory Catalogue (USNO) with their counterparts in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS).

They were left with about 290,000 missing objects, most of which could easily be accounted for on closer inspection. Eventually they found a single star that genuinely seemed to have disappeared, and even that discovery came with lingering doubts.

It was an intriguing find, but hardly constituted compelling evidence of new kinds of astrophysics.

In this latest study they compared 600 million objects in the USNO catalogue with a collection put together by the University of Hawaii's Pan-STARR system.

The naval catalogue spans around 50 years of sky surveys, capturing details of the entire sky in five colours down to a visual magnitude of about 21. The cosmic objects in the Pan-STARR data release include slightly dimmer objects, down to a magnitude of roughly 23 as compared to the SDSS's 22.

Having more stars to compare means potentially more 'missing' stars, while capturing objects of a lower magnitude means making extra sure there's nothing sitting in the star's place.

The comparison revealed 151,193 candidates for missing stars. This number was whittled down to 23,667 possibilities by widening the search field, cutting away stars that seemed to have moved farther than expected.

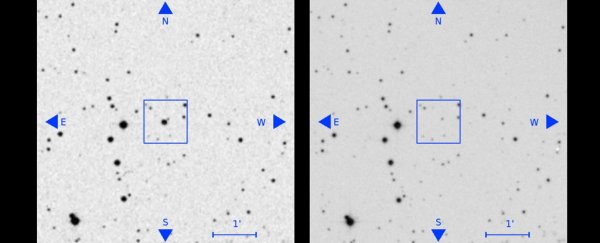

That short list was visually inspected, excluding around 18,000 images that were messed up by flaws or artefacts. Lastly, the team removed images where the missing star was towards the edge of the field, just to reduce risk of any false positives.

One final sweep using yet another method for comparisons removed other possible flaws in data collection, or unclear results. That left 100 dark shadows where a star once shone.

When a star dies, it usually goes out with a bright shout as a super nova, or quietly fades into a softly glowing ember like a white dwarf. They don't tend to just stop shining.

There could be some clues in the fact that the pool of candidates were in general a little redder in colour than the typical USNO catalogue object, and were generally faster moving. Working it out will take further research.

"We are very excited about following up on the 100 red transients we have found," says Villarroel.

There are plenty of explanations that need exploring before we can be confident this represents anything exotic, something the team hopes to accomplish with citizen science projects.

One possibility is that the object occasionally flares enough to be seen before dimming again a few magnitudes. Another explanation – although very unlikely – is they're all just scratches after all, and never existed to begin with. It could also be a dull star we assumed was farther away and has just moved too far to be noticed.

A more exciting thought is that a few might be super-rare failed supernovas, forming black holes without the fireworks display. As cool as that would be, it's a stretch to think this would explain all of the observations.

If the disappeared stars turn out to be none of these things, we may need to entertain new physics.

"We believe that they are natural, if somewhat extreme, astrophysical sources," says Martin López Corredoira from the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias in the Canary Islands.

There is that other explanation. The one we'd all like to be true, but can't take seriously until we have a lot more evidence: Aliens could be covering these stars up to absorb their light, converting it into useful energy before shedding it as low grade radiation. Or the initial flares might be short lived, intense signals from alien technology.

In moments like this, we can all let our imaginations run a little wild, even if the researchers are hesitant.

"But we are clear that none of these events have shown any direct signs of being ETI [extra terrestrial intelligence]," says Corredoira.

Which might just be what the aliens want us to think.

This research was published in the Astronomical Journal.