We've been gazing out at the Solar System for a very long time, and by now we know, more or less, where things go. Sun, planets, asteroid belt, more planets, then millions more asteroids (we're not really sure how many). Maybe another planet. OK, so it's a little tricky.

But a new discovery has hinted that maybe there could be more asteroids in the "Sun, planets" section. Perhaps even loads more.

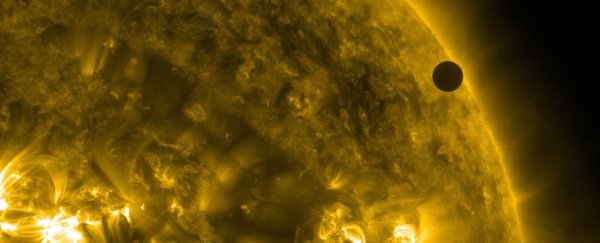

It's called 2019 AQ3 - an asteroid whose tight elliptical orbit is nearly always closer to the Sun than Venus, and even dips closer than Mercury. It takes just 165 days to orbit the Sun - the shortest year ever seen in a Solar System asteroid. (A Venusian year is 225 days; a Mercurian year is 88.)

"We have found an extraordinary object whose orbit barely strays beyond Venus's orbit - that's a big deal," said astronomer Quanzhi Ye of the Infrared Processing and Analysis Center (IPAC) at Caltech.

"There might be many more undiscovered asteroids out there like it."

Ye first spotted the object on 4 January 2019 in data from the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF), an automated sky survey project run out of Caltech's Palomar Observatory. It wasn't long before its unusual nature became clear to other astronomers, and multiple telescopes were deployed to study it on January 6 and 7.

In addition, the archives of the Pan-STARRS 1 telescope at the Haleakalā Observatory in Hawai'i turned out to contain previously unnoticed evidence of the asteroid, dating back to 2015.

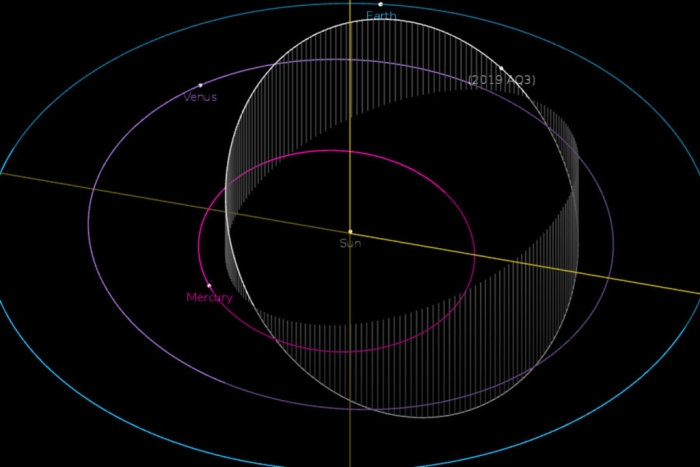

Based on the archival data and the new observations, the researchers were able to make an accurate calculation of 2019 AQ3's orbit. It travels in a strange loop that takes it above and below the Solar System's orbital plane - strange because most things in the Solar System within the Oort Cloud follow that plane pretty neatly.

(NASA/JPL-Caltech)

(NASA/JPL-Caltech)

And, as mentioned, its closeness to the Sun is also strange. Of all the asteroids in the Solar System - and there are a lot - we've found only 19 (including 2019 AQ3) whose orbits are completely contained within Earth's orbit.

These asteroids are known as Atira asteroids, Apohele asteroids, or Interior-Earth Objects (IEOs), and, while they don't represent a current threat, this could change in the future if their orbits are perturbed by Venus or Mercury.

And 2019 AQ3 seems to be quite sizeable. We don't know of many asteroids that are of the size 2019 AQ3 appears to be; although it's impossible to give exact dimensions based on the limited observations to date, current estimates put it at up to 1.6 kilometres (1 mile) across.

"This is one of the largest asteroids with an orbit entirely within the orbit of Earth - a very rare species," Ye said. "In so many ways, 2019 AQ3 really is an oddball asteroid."

Looking for Atira asteroids and near-Earth asteroids and comets that are potentially hazardous to Earth is just one of ZTF's goals. With its wide field-of-view and fast readout electronics, it's designed to catch objects that move or occur quickly, called transient events.

These include asteroids, supernovae and even black holes - and since first light in March 2018, less than a year ago, ZTF has helped identify more than 1,100 transients.

"ZTF is surveying the whole northern sky every three nights," said Shri Kulkarni, principal investigator of the facility. "It's already discovering a few supernovae a night, and we expect that rate to go up."

Overall, the project has identified 50 near-Earth asteroids, including 2018 NX and 2018 NW, that skimmed Earth at distances of only 115,800 and 112,300 kilometres (72,000 miles and 76,000 miles), respectively.

It also identified two black holes spotted as they shredded stars, nicknamed Ned Stark and Jon Snow.

Papers describing these discoveries will be published in a special ZTF issue of the journal Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific.