Scientists are finding microplastics unnervingly close to developing fetuses during pregnancy.

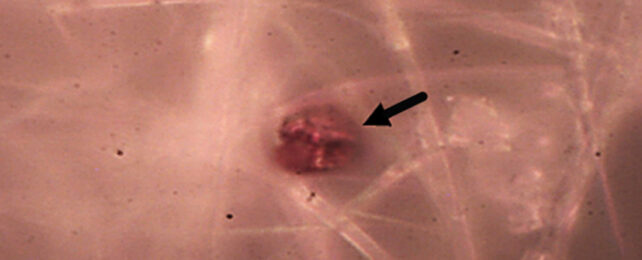

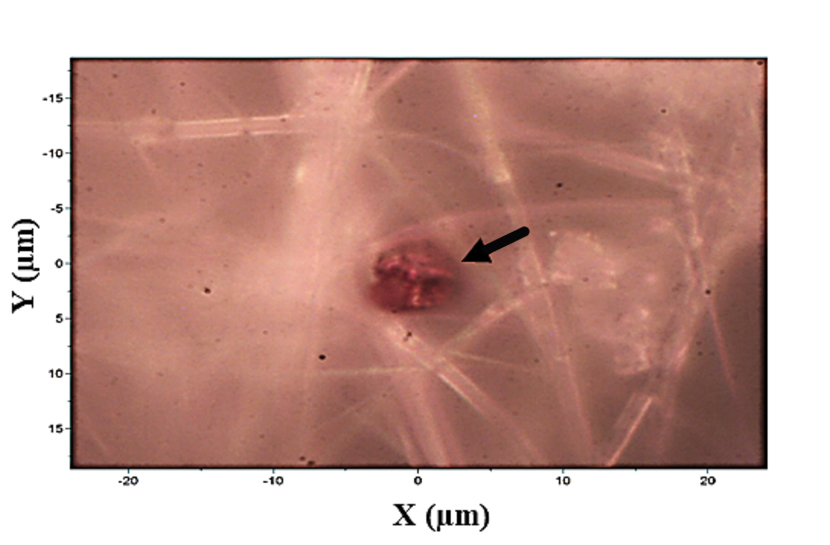

In just the past few years, preliminary research has turned up microscopic bits of plastic floating in a few dozen samples of human placenta – the organ that provides oxygen and nutrients to a growing fetus.

A new analysis on donated placental tissues now expands on those results and hints at an alarming trend.

When researchers at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, the Kapiʻolani Medical Center for Women & Children, and Federal University of Alagoas, Brazil, analyzed 30 placentas donated between 2006 and 2021, they found plastic contamination had increased significantly over time.

In 2006, only six of the the ten donated placentas contained microplastics. By 2013, nine out of ten placentas were found to be contaminated. In 2021, each of the ten placentas anayzed showed plastic pollution, and the sizes of the microplastic particles were bigger than ever.

"We believe that the plastics may be floating around in food or being inhaled. It's coming through our digestive fluids or lungs, and the particles are getting absorbed through the gut and traveling through the bloodstream, and then somehow collecting in the placenta during pregnancy," explains obstetrician and researcher Men Jean Lee from Kapiʻolani Medical Center.

"The big question is, as it's traveling through the placenta, can it get through the umbilical cord and then to the baby? We don't know that right now."

The study is the largest of its kind, and yet the sample size is still too small and regionally limited to draw any firm conclusions about the cause or effect of microplastic pollution on a developing fetus or the mother.

The results do, however, track the relentless growth of ongoing plastic production, consumption, and pollution, globally.

Exposure to microplastics now seems all but impossible to avoid, and the effect on human health remains largely unknown.

By some estimates, the average person inhales about a credit card's worth of plastic a week, some pieces of which can get stuck deep into your lungs. And that's just the plastic that you breathe.

Tiny fragments are also present in drinking water and food, and in preliminary research on mice, it looks as though these pollutants can infiltrate every organ of the rodent's body.

Other recent studies on humans have found microplastics floating in breastmilk and the first poop of newborns.

In 2020, scientists discovered the first evidence of microplastics, smaller than five millimeters, in the human placenta. These results, however, were only based on roughly a handful of specimens.

Later, another team evaluated the presence of microplastics in 17 placentas and found similar results.

While the health effects of plastic in the placenta are unknown, early experiments on mice suggest that micro- and nanoplastics have the "potential to disrupt fetal brain development, which in turn may cause suboptimal neurodevelopmental outcomes."

The high rate of placental contamination recently found in Hawaiʻi may not apply elsewhere in the world. People on islands, for instance, tend to eat more seafood, which is heavily exposed to ocean plastic, and remote locations tend to be more reliant on single-use plastics as a whole. The Hawaiʻian islands are also relatively close to the Great Pacific Garbage Patch.

"The findings of this study, based on placental samples collected in Hawaiʻi, provide insight into the vulnerability and sensitivity of Pacific Island communities to plastic pollution due to our remote location in the Pacific Ocean," Lee and colleagues write in their paper.

"Since the entire State of Hawaiʻi State is designated as a coastal community, pregnant women who live there appear to be particularly vulnerable to marine plastic pollution, with yet unclear effects on maternal and fetal health."

The study was published in Environment International.