Microplastics are everywhere. Even what should be untouched wildernesses – the icy plains of Antarctica, the crushing depths of the deepest ocean chasms – has been polluted by our garbage.

So it's no surprise that we ingest plastic, too; it's been found in our feces, probably as a result of eating from plastic containers. But a new pilot study has found something borderline shocking: Babies have greater concentrations of microplastics in their guts than adults living in the same area.

Specifically, on average, more microplastics were found in the feces of six one-year-old babies in New York City than in the feces of 10 adults. The meconium (earliest stool) of three New York newborns, meanwhile, had concentrations closer to those of adults.

The finding suggests that infants have a higher exposure to microplastics than adults do, possibly due to factors such as child-safe plastic feeding utensils, pacifiers, sippy cups and plastic toys that babies like to chew on while teething.

The results demonstrate that this phenomenon requires further investigation, especially since any health impacts on babies could be a lot more severe.

"Our data provide baseline evidence for microplastic exposure doses in infants and adults and support the need for further studies with a larger sample size to corroborate and extend our findings," the researchers wrote in their paper.

The health impacts of ingesting microplastics are currently unknown, but it may not be as harmless as we once thought. Recent studies suggest that microplastics below a certain size threshold can cross cell membranes and enter the circulatory system, and can negatively impact cell function.

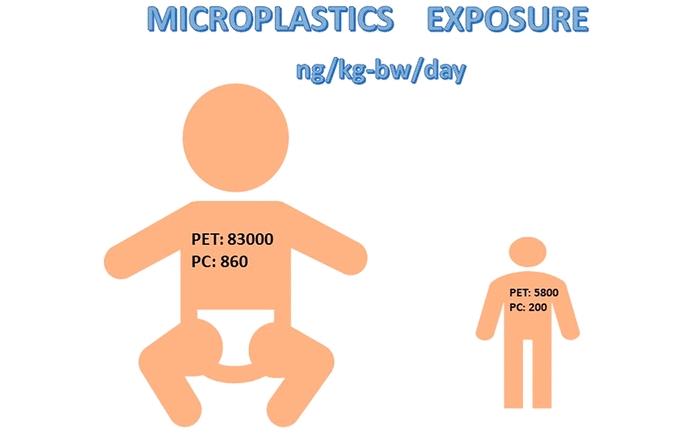

A team of researchers led by pediatrician Kurunthachalam Kannan of New York University wanted to assess human exposure to two common types of microplastic – polyethylene terephthalate (PET), used to make food packaging and clothing, and polycarbonate (PC), used in toys and bottles.

The researchers collected samples of feces from 6 one-year-old infants and 10 adults, as well as meconium from 3 newborn babies. They subjected these samples to mass spectrometry, after scanning samples of plastic to get an accurate signature to look for in the fecal samples. Every fecal sample contained at least one type of plastic, but the difference between adults and one-year-olds was striking.

"We found significant differences in the patterns of two types of microplastics between infant and adult feces," the researchers wrote in their paper.

"PET concentrations were significantly higher in infant feces than in adult feces, whereas concentrations of PC microplastics were not significantly different between the two age groups. The microplastics measured in infant and adult feces were thought to be primarily derived from dietary sources."

(Zhang et. al., Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett., 2021)

(Zhang et. al., Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett., 2021)

On average, the infant feces contained over 10 times more PET than adult feces. Although the sample size was too small to conclusively rule what the reasons might be for this huge discrepancy, there are a range of possibilities.

Plastic feeding utensils, cups and bowls are considered safer for babies, since they are more difficult to break and therefore less likely to produce sharp shards, as glass and ceramic can do. There are also plastic teething products designed for babies to chew, and plastic toys not necessarily designed for chewing, but that end up munched anyway, because that's what babies do.

"One-year-old infants are known to frequently mouth plastic products and clothing. In addition, studies have shown that infant formula prepared in PP bottles can release millions of microplastics, and many processed baby foods are packaged in plastic containers that constitute another source of exposure in one-year-old infants," the researchers wrote.

"Furthermore, textiles are a source of PET microplastics. Infants often chew and suck cloths, and therefore, exposure of this age group to microplastics present in textiles is a greater concern."

These findings demonstrate, the researchers said, a need to conduct deeper investigation into this phenomenon.

The research has been published in Environmental Science & Technology Letters.