Blazing colors and enticing scents may be showy, but they're just one part of the toolkit plants use to lure in pollinators.

Some plants produce heat, and a new study reveals for the first time that this warmth attracts insects, which in turn aid pollination. In fact, this may have been among the first pollinator-attracting strategies to emerge in the plant kingdom, hundreds of millions of years ago.

These plants are cycads, a botanical group that has evolved comparatively little since the Jurassic. The particulars of their heat-producing ability elucidate the fascinating co-evolution of plants and the pollinators on which they rely for reproduction.

"Long before petals and perfume," says Harvard University evolutionary biologist Wendy Valencia-Montoya, "plants and beetles found each other by feeling the warmth."

Related: Plants Really Do 'Scream'. We've Simply Never Heard Them Until Now.

For decades, scientists have known that plants – including cycads – have thermogenic capabilities, or an ability to produce heat. Some are even able to generate temperatures up to 35 degrees Celsius higher than the ambient temperature.

Valencia-Montoya and her colleagues thought that, in the case of cycads, the sheer cost of heat production implied benefits. What if, they reasoned, the heat generated by cycads was a reproductive strategy?

Cycads look a bit like tree ferns, a group to which they are unrelated. They have cylindrical trunks and stiff, feather-shaped leaves that sprout from the top, and cones that serve as reproductive structures.

They're also dioecious, meaning that individual trees produce only male or female gametes. Male trees grow pollen-producing cones, and female trees grow cones that produce ovules that, when pollinated, develop into seeds.

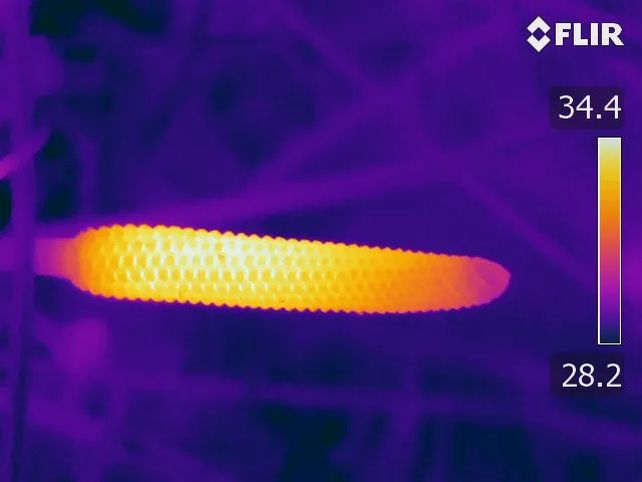

Heat generation is confined to the cones, so a reproductive strategy for thermogenesis seemed like a reasonable hypothesis. The hard part, however, was proving it.

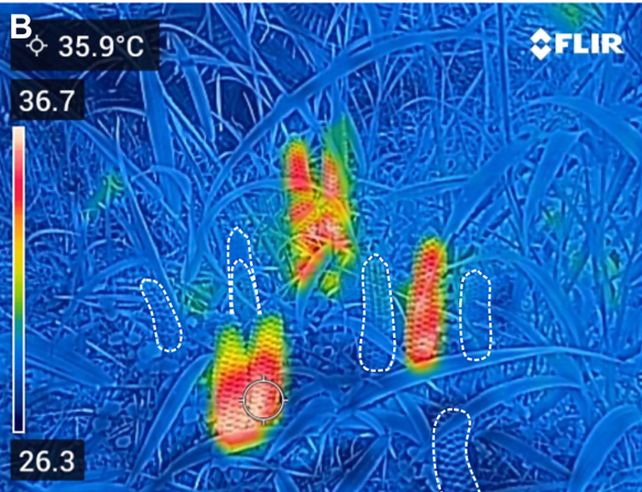

The researchers focused their efforts on a species called Zamia furfuracea, which is found in Mexico. It relies exclusively on a beetle species called Rhopalotria furfuracea for pollination.

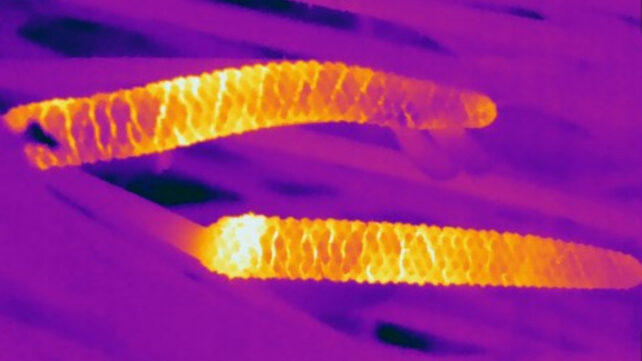

The researchers took thermal images of the plants and discovered that the cones heat up on a strict circadian rhythm, at the same time every day. Starting about mid-afternoon, the temperature in the male cones rises and peaks before subsiding. The female cones heat up three hours later.

This cycle repeats every 24 hours, suggesting an internal genetic clock drives the process, rather than cues from light, moisture, or temperature.

The behavior of the beetles is where it gets really interesting. As the male cones heat up, the beetles flock to them. Then, as the temperature rises in the female cones, the beetles move to them accordingly – bringing a dusting of pollen.

"This was one of the early compelling pieces of evidence that this is probably related to pollination," says cellular biologist Nicholas Bellono of Harvard University. "Male and female plants were actually heating in a circadian-controlled manner – and we could see it locks with the beetle movement."

A closer examination of both plants and beetles revealed the biological mechanisms driving this fascinating symbiosis.

For the plants, a gene called AOX1 kicks into overdrive, bypassing the mitochondria's normal ATP production and causing these engines to convert fuel directly into heat, producing the steady, sustained elevations in temperature that attract the beetles.

Meanwhile, the beetles possess sensors at the tips of their antennae called coeloconic sensilla that directly respond to thermal infrared radiation using the TRPA1 ion channel – the mechanism behind heat sensing in other animals such as snakes.

By eliminating other environmental cues that the beetles could react to, the researchers confirmed that the beetles do indeed home in on radiant heat. Disabling the ion channel prevented the beetles from responding to the same stimulus, providing the first direct link ever observed between TRPA1 heat sensing and pollination.

Today, there are just 300 cycad species left in the world, most of them considered endangered. This could be partly due to the emergence of flowering plants, which rose to dominance between 112 and 93 million years ago.

Infrared offers only a single-channel signal – intensity – whereas color offers nearly infinite combinations. As flowering plants diversified and insects evolved richer color vision, cycads' simpler thermal signals may have become a disadvantage.

In addition, as flowering plants proliferated, insects may have changed in response, developing more complex color vision and sensory capabilities, while the cycad-pollinating beetles remained specialized for nighttime infrared cues.

Interactions between plants, their symbionts, their pollinators, their predators, and in some cases their prey, are difficult for humans to discern. This finding suggests that we have barely begun scratching the surface.

"This is basically adding a new dimension of information that plants and animals are using to communicate that we didn't know about before," Valencia-Montoya says. "We knew of scent, and we knew of color, but we didn't know that infrared could act as a pollination signal."

The research has been published in Science.