Astronomers have detected 72 incredibly bright and quick events flashing across a recent sky survey - and they're struggling to understand where they came from.

The mysterious explosions are similar in brightness to supernovae - the final, gigantic explosions that extinguish stars.

But supernovae can be seen lighting up the sky for several months or more.

In contrast, these 72 mysterious explosions were visible from a week to a month - which is incredibly brief on a cosmological timeframe.

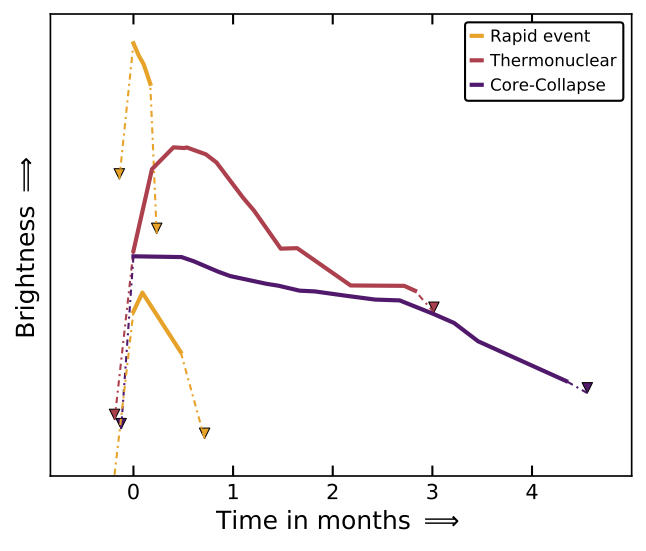

You can see two examples of the newly detected rapid events in yellow on the graph below, compared to two typical supernovae types (red and purple).

(M. Pursiainen/University of Southampton)

(M. Pursiainen/University of Southampton)

The rapid events are so far known only as transients, and were detected in data from the Dark Energy Survey Supernova Programme (DES-SN).

The DES-SN is an international effort that's hunting down supernovae to better understand dark energy, the hypothetical force thought to be driving the expansion of our Universe.

By tracking these bright flashes of exploding stars, researchers hope to get a better understanding of exactly how fast the Universe is spreading out.

But within that data, the international team of astronomers also noticed a number of other, more rapid explosive events - and they're not sure what's causing them.

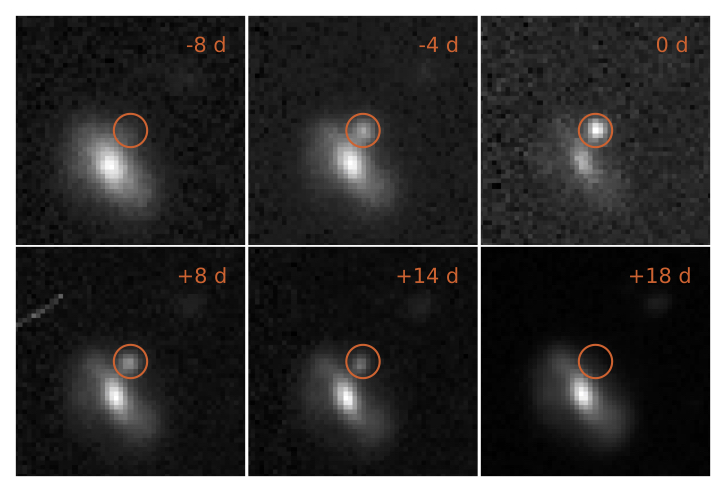

Here's one of the transient events photographed from eight days before maximum brightness to 18 days afterwards:

(M. Pursiainen/University of Southampton)

(M. Pursiainen/University of Southampton)

This transient event took place 4 billion light years away.

"The DES-SN survey is there to help us understand dark energy, itself entirely unexplained. That survey then also reveals many more unexplained transients than seen before," says one of the astronomers, Miika Pursiainen from the University of Southampton.

"If nothing else, our work confirms that astrophysics and cosmology are still sciences with a lot of unanswered questions!"

So far there's a lot we don't know. But what's clear is that the events are both incredibly hot in temperature, and large in scale - with temperatures ranging from 10,000 to 30,000 degrees Celsius (18,000 to 54,000 degrees Fahrenheit).

The explosions also range in size, stretching from several to up to a hundred times the distance from Earth to the Sun (Earth is 150 million kilometres or 93 million miles from the Sun).

Even stranger, the explosions seem to be expanding and cooling as they evolve in time.

It's still early days, but there are already a few ideas circulating on what they could be.

One option is that this is a strange, never-before-seen type of supernova where the star sheds a lot of material before it explodes.

In this scenario, the star could become completely enveloped by a shroud of matter, which becomes incredibly hot. It's this hot cloud of matter that the astronomers are detecting rather than the star itself.

There's also the possibility that we're seeing a newly discovered supernova in action.

Just last week, researchers discovered a brand new explosive type of star death. The newly discovered supernova, KSN 2015K, peaked in brightness and then faded completely in under a month - 10 times faster than other supernovae of similar brightness.

In the case of KSN 2015K, researchers think the star was shrouded by a cocoon of dust it had already ejected - only becoming visible after the dust was blasted away by the supernova's shockwave.

It's unclear if these fast transients could be further evidence of this newfound star death in action, or represent an entirely new astronomical phenomenon.

To test these hypotheses - or come up with other options - the team needs a lot more data.

They're going to continue to use a telescope in the Chilean Andes to monitor the night sky for traces of these explosions, and get a sense of why they occur, and how often.

One important thing they'll be looking for is if these events are more or less common, compared to 'standard' supernovae.

The team also hasn't published their detections in a peer-reviewed journal as yet, so there's still the opportunity for other researchers to add insights and alternative explanations.

We still have a lot to learn, but we'll make one prediction - this won't be the last you'll hear about these 72 explosions.

The results were presented on Tuesday 3 April at the European Week of Astronomy and Space Science in Liverpool, UK.