A giant explosion that lit up the sky didn't just rock the cosmos – it absolutely rattled our understanding of the Universe's most powerful outbursts.

The gamma-ray burst (GRB) recorded on 2 July 2025 is the longest of its kind ever observed, lasting about a day. By comparison, GRBs normally last on the scale of milliseconds to minutes at most.

Moreover, it did something astronomers have never seen a GRB do before: it appears to have repeated. This can't be neatly explained by our current models for what causes them.

Related: Brightest Space Explosion Ever May Hide an Elusive Dark Matter Particle

"This event is unlike any other seen in 50 years of GRB observations," says astrophysicist Antonio Martin-Carrillo of University College Dublin.

"GRBs are catastrophic events so they are expected to go off just once because the source that produced them does not survive the dramatic explosion. This event baffled us not only because it showed repeated powerful activity but also because it seemed to be periodic, which has never been seen before."

GRBs are the Universe's most violent explosions, powerful eruptions that blaze with the most energetic form of radiation – gamma rays. Each burst releases more energy in a few seconds than the Sun will over the entire course of its lifespan.

There are thought to be two main mechanisms behind them: First, a core-collapse supernova of a massive star, wherein the stellar core collapses under gravity to form a black hole. This produces what we call long-duration bursts, lasting more than two seconds.

The second mechanism involves two neutron stars colliding and merging. This produces bursts shorter than two seconds.

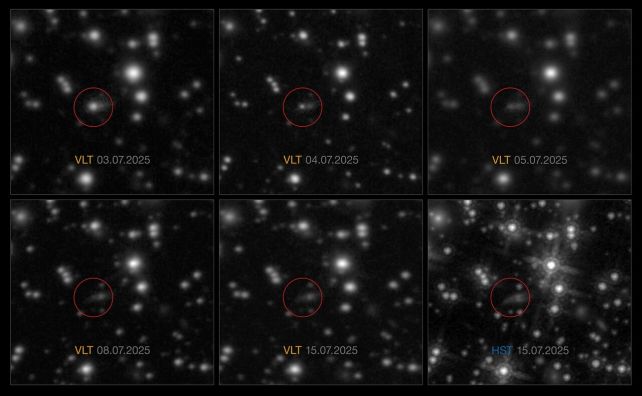

The unusual nature of this new detection, designated GRB 250702B, was obvious immediately. It was discovered from alerts delivered by NASA's space-based Fermi gamma-ray telescope – not just once, but three separate times over the course of several hours as the object seemed to pulsate in multiple repeated bursts of gamma rays.

The research team, co-led by Martin-Carrillo and astrophysicist Andrew Levan of Radboud University in the Netherlands, scurried to get to the bottom of this absolute space oddity.

Checking other telescope data revealed that the Einstein Probe, a space-based X-ray observatory, showed the same source had been sending out X-rays almost a full day before the Fermi observations.

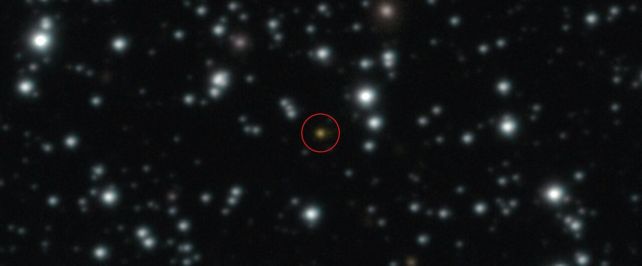

It was so bright that astronomers initially thought that the source was right here in the Milky Way. However, when they trained the Very Large Telescope and the Hubble Space Telescope to the spot in the sky where it came from, they discovered otherwise.

It's unclear exactly how far away it is, but the progenitor of the weird event is also weird: a galaxy with a very strange shape, appearing to be split into two distinct regions. This could be a clue about what produced the explosions, but at the moment it's still one heck of a mystery.

"If a massive star – about 40 times the mass of the Sun – had died, like in typical GRBs, then it had to be a special type of death where some material kept powering the central engine. Alternatively, the periodicity of the flashes of gamma-ray radiation could be caused by a star being ripped apart by a black hole, a phenomenon known as a tidal disruption event (TDE)," Martin-Carrillo explains.

"However, unlike more typical TDEs, to explain the properties of this explosion would require an unusual star being destroyed by an even more unusual black hole, likely the long-sought 'intermediate mass black hole'. Either option would be a first, making this event extremely unique."

To figure out what the heck GRB 250702B was, one of the first steps is to calculate the distance to the galaxy that produced it. Only then will astronomers be able to calculate its exact brightness – a measurement that will help narrow down how much energy it released, and how it may have been produced.

"We are still not sure what produced this or if we can ever really find out," Martin-Carrillo says, "but with this research, we have made a huge step forward towards understanding this extremely unusual and exciting object."

The discovery has been detailed in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.