Don't you just hate it when you're just minding your own business, and a star suddenly decides to go supernova? Well, good news: Scientists have figured out what these stars look like right before they die.

According to new simulations, the massive stars that are the progenitors of neutron stars dim dramatically in the last few months before they explode. So, if a massive star fades into complete obscurity without fanfare, the odds are good that there's a supernova on the horizon.

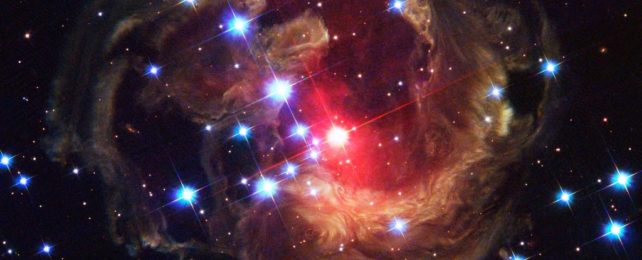

Red supergiant stars clocking in at around 8 to 20 times the mass of the Sun are some of the most interesting to watch. These beasts are at the end of their lifespan, running dangerously low on the fuel they need to support nuclear fusion in their cores.

That fusion provides outward pressure against the inward pressure of gravity. Take the fusion away, and things get violent. The star goes kaboom, star guts explode into space, and the stellar core collapses (for most stars).

For the red supergiants in question here, that core turns into an ultradense neutron star, something between around 1.1 and 2.3 times the mass of the Sun, packed into a sphere just 20 kilometers (12 miles) across.

However, before the big show kicks off, the star loses a lot of mass. We don't really understand red supergiant mass loss very well on a theoretical level.

By looking at the light and dust that results from the death of a red supergiant after the fact, scientists have ascertained that the red supergiants shed a lot of gas and dust in the lead-up to the supernova, but the timescale on which this happens is unclear.

Could it be over decades, as past research suggests, or in less than a year, as some other modeling studies predict?

Led by astrophysicist Benjamin Davies of Liverpool John Moores University in the UK, a team of researchers used observational evidence and simulations to reconstruct how a dying red supergiant evolves.

They conducted simulations and found that the immense cloud of material around the star blocks optical light by a factor of 100 and near-infrared light by a factor of 10 just before the star goes supernova.

"The dense material almost completely obscures the star, making it 100 times fainter in the visible part of the spectrum," Davies explains. "This means that, the day before the star explodes, you likely wouldn't be able to see it was there."

To gauge how long the mass loss takes, the researchers went hunting for observational clues. They found several archival images of red supergiant stars that later went supernova, around a year after the image was taken. They say this is evidence that the large-scale, obscuring mass loss occurs at least within a year.

That rules out the imminent demise of Betelgeuse (although we did already know that). The mass loss episode that dimmed Betelgeuse in 2019 seems to be part of a slower process; the latest estimates put the star 1.5 million years away from supernova.

When that day comes, now we'll know what to be alert for … if we're still around.

"Until now, we've only been able to get detailed observations of supernovae hours after they've already happened," Davies says.

"With this early-warning system, we can get ready to observe them real-time, to point the world's best telescopes at the precursor stars, and watch them getting literally ripped apart in front of our eyes."

The research has been published in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.