A predator that swam Earth's oceans more than half a billion years ago is unlike any creature that lives on our planet today.

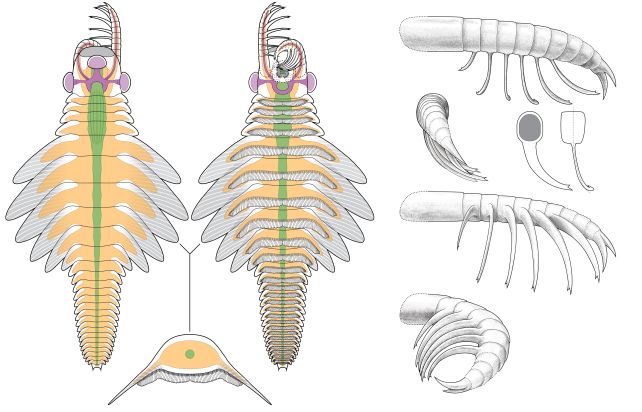

Mosura fentoni possessed three eyes, grasped its prey with spiny claws, ate with a circular, tooth-lined maw, swam with the aid of flippers that lined either side of its body, and had 26 body segments – more than any other radiodont, the extinct group of animals to which it belonged.

Luckily, it would only have been about as long as your finger – most things back then were pretty small. But its segmented tail end has fascinated paleontologists Joe Moysiuk of the Manitoba Museum and Jean-Bernard Caron of the Royal Ontario Museum, who characterized the strange beastie from its fossilized remains in the famous Burgess Shale.

They named Mosura for its resemblance to a moth, even though the relationship is distant and tenuous.

"Mosura has 16 tightly packed segments lined with gills at the rear end of its body," Moysiuk explains. "This is a neat example of evolutionary convergence with modern groups, like horseshoe crabs, woodlice, and insects, which share a batch of segments bearing respiratory organs at the rear of the body."

The oceans of Earth's Cambrian period, between around 539 and 487 million years ago, were a different place than our planet today. That was when life really took off, and the ocean started to thrive.

We don't have many records of that time, but the Burgess Shale is, really, if we're being completely frank, a marvel of fossil preservation. It formed around 508 million years ago, when silty mud flowed across the seafloor, trapping and preserving a large number of organisms as it went.

That mud became a fossil bed known as a Lagerstätte, so exceptional that fine details, soft tissue, and even internal structures were captured in the sediment. It revealed a rich ecosystem filled with mysterious creatures so bizarre that we've often been left baffled and wrong about their anatomy.

In this environment lived the radiodonts, a group of animals that shared a common ancestor with arthropods, but has since gone extinct. This group includes the famous Anomalocaris, a fearsome beast that could have grown up to a meter long. That might not seem very large to us, but back then, when most things were small, it was a giant.

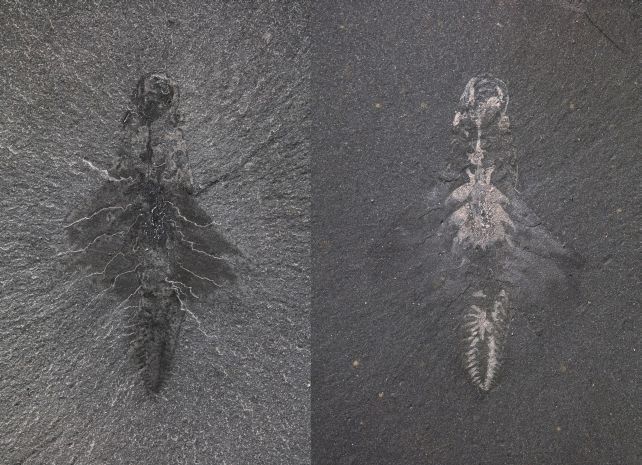

Mosura was not a giant, but it was one-of-a-kind, at least as far as we know. Moysiuk and Caron studied 61 fossilized individuals of the species, and characterized it in detail.

"Very few fossil sites in the world offer this level of insight into soft internal anatomy," Caron says. "We can see traces representing bundles of nerves in the eyes that would have been involved in image processing, just like in living arthropods. The details are astounding."

Of particular interest was the animal's circulatory system. It did not involve veins, as the circulatory systems of vertebrates do, but was instead open, like the circulation of modern arthropods. In crabs, spiders, insects, and other arthropods, the heart simply pumps blood (or hemolymph) into cavities in their bodies, where it swirls around their organs to perform its function.

In Mosura, these cavities are called lacunae. They filled the creature's body, and extended into the swimming flaps that extended from each segment, visible as reflective patches in the fossils.

"The well-preserved lacunae of the circulatory system in Mosura help us to interpret similar, but less clear features that we've seen before in other fossils. Their identity has been controversial," Moysiuk says. "It turns out that preservation of these structures is widespread, confirming the ancient origin of this type of circulatory system."

As for its strange, powerful respiratory system at the rear end of its body, its specialized structure suggests Mosura may have had unique needs. Perhaps its habitat was different from that of other radiodonts, or maybe its hunting methods required enhanced respiratory functions.

This is one of those questions that is impossible to answer without more information. However, Mosura is a beautiful example of the strategies life adopts to thrive according to circumstance.

"Radiodonts were the first group of arthropods to branch out in the evolutionary tree, so they provide key insight into ancestral traits for the entire group," Caron says. "The new species emphasizes that these early arthropods were already surprisingly diverse and were adapting in a comparable way to their distant modern relatives."

The research has been published in Royal Society Open Science.