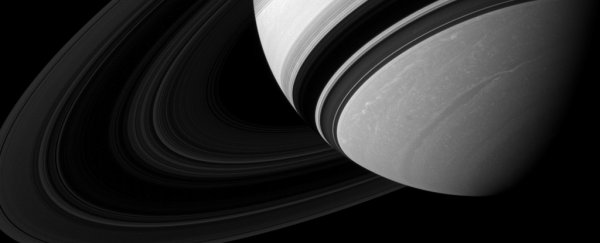

Although Cassini's demise was the end of an era for unprecedented Saturn observation, it also went out on a high note.

As it swooped between Saturn and its rings in preparation for its final plunge, the spacecraft captured as much information as it could - and beamed it back to scientists on Earth.

Now astronomers have announced that as Cassini passed through Saturn's ionosphere, at altitudes between 2,600 and 4,000 kilometres (1,615 and 2,485 miles), it found something curious: the shadows cast by the rings block the Sun's ultraviolet radiation, reducing ionisation in those regions.

Effectively, the rings significantly change the gas giant's atmosphere in a way we didn't know about before.

That Saturn's rings are more than just a pretty face has been known for a while. In the 1980s, NASA scientists theorised that bands on Saturn could have been caused by rain of charged water particles from the planet's rings - and in 2013, they announced that they'd found evidence for it.

Cassini's data from its 11 orbits reveals a different effect though - a clear difference in the planet's cold, dense ionosphere - a layer in the planet's upper atmosphere between 300 and 5000 kilometres (186 and 3,107 miles) in altitude, ionised by ultraviolet radiation.

Of course, Saturn doesn't actually have a solid surface, but for research purposes the zero altitude mark has been set at the point of one bar of pressure, around the pressure at sea level here on Earth. That's 60,268 kilometres (37,449 miles) from the planet's centre.

Researchers from the Swedish Institute of Space Physics and NASA Goddard have found that there is less ionisation and a noticeable drop in plasma in places where the ring shadows fall.

They concluded that the B-ring and most of the A-ring must be opaque to extreme ultraviolet radiation. Meanwhile, the effect was not observed for the C and D rings, which therefore must allow ultraviolet radiation to pass through.

The scientists also found that the ionosphere was a lot more varied than they expected, with electron density sometimes changing drastically between one orbit and the next. This variation could not be explained by the shadows alone.

The team suggests that the variation could possibly be caused by the "ring rain" - even though the phenomenon has never actually been observed. Another possibility is that strong longitudinal winds are having an effect on electron density.

"I think the jury is out on ring rain," co-author William Kurth of the University of Iowa told Newsweek. "Radio and plasma wave observations - coupled with others - will ultimately shed light on this."

Cassini made its first swoop of its final mission between Saturn and its rings on 26 April, 2017. It made 22 such orbits in total before plunging into the planet's mysterious depths. The research team only studied half of these orbits, and used no data from the final plunge.

This is just a small portion of the information Cassini still has yet to reveal.

The research was presented at the Fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union, and published in the journal Science.