Phage therapy, where viruses are used to kill bacteria, became common in the 1920s, before antibiotics arrived to offer easier and more effective ways of treating infections. However, with antibiotic resistance now a growing problem, phage therapy might be set for a dramatic comeback.

We know that bacteria are continually evolving to put up better defenses against the drugs we're throwing at them, so treatments that were once very effective can sometimes end up being useless. It's a major problem for public health.

In a new study, led by researchers from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in Israel and the University of Melbourne in Australia, phage therapy shows promise in the fight against antibiotic resistance.

Still, there are challenges to overcome. Bacteria can also develop tricks to outsmart the bacteriophages behind phage therapy, so understanding how that occurs will be important, moving forward.

Related: Your Own Mouth Bacteria Could Give You a Heart Attack, New Study Suggests

"Understanding the arms race between phages and bacteria not only deepens our knowledge of how bacteria defend themselves but also opens the door to next-generation treatments," writes molecular biologist Debnath Ghosal, from the University of Melbourne.

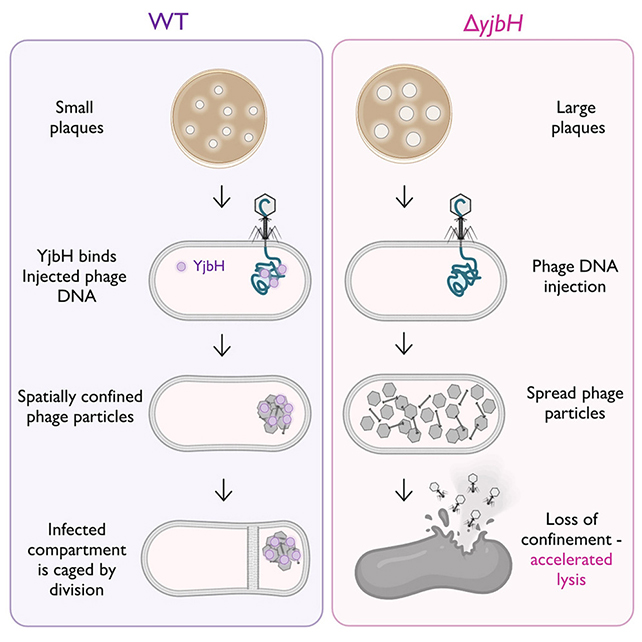

The researchers took a close look at the bacterium Bacillus subtilis and a variety of phages used to tackle it. Watching B. subtilis work through its blocking tactics, researchers found the protein YjbH – seen in many bacteria – played a significant role.

Bacteriophages work by attaching themselves to bacteria cells, essentially hijacking these cells to duplicate and spread. That's done with an injection of bacteriophage DNA, and eventually the bacterial cell bursts, releasing more phages.

What YjbH does is sense this invasion and take steps to limit the damage, effectively roping off the spot where the bacteriophage has attached itself. The cell then divides, in an attempt discard the roped off area and hopefully survive destruction.

"This 'exclude and survive' defense mechanism may represent a prevalent strategy employed by the host to contain viral spread," write the researchers in their published paper.

It's an impressive escape strategy, and it's the first time scientists have seen it used to defend against bacteriophage attack. Before now, it was thought to be something only more complex, multicellular organisms could do.

Now we're aware of it, of course, we might be able to develop phage therapy approaches that get around it too – making phage therapy a more viable alternative or complementary treatment to antibiotics.

That's still a long way off, because bacteria defense mechanisms are just one of several issues with phage therapy. Recent studies have found this strategy to be limited in its effectiveness, in part because the body's immune system sees the bacteriophages as threats, and works to try to wipe them out.

However, plenty of groups think there's enough potential here – and enough of a crisis in terms of antibiotic treatments – for further investigation into phage therapies to be worthwhile, which is the plan for the researchers behind this study.

"We hope that by reactivating phage therapy, we can contribute to non-antibiotic treatments for infections," writes Ghosal.

"With so many antibiotic-resistant infections emerging, after 100 years, it's time to reconsider the benefits of phage therapy."

The research has been published in Cell Reports.