Advances in the development of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 are prompting medical systems around the world to prepare to roll out local immunisation programmes to build herd immunity against the pandemic.

The unprecedented scale of the endeavour makes it hard to predict precisely when we might all expect to get a shot against COVID-19. Not only will it depend on where you live, some members of the population will be prioritised over others.

With two front runners in the race for a vaccine being based in the US, UK and American citizens will be among the first to receive the benefits of new vaccine technology.

UK citizens received the first of 800,000 vaccines produced by Pfizer on December 8, 2020, with vulnerable citizens targeted in the initial wave. Frontline and healthcare workers, those over 65, and anybody with a condition that puts them at greater risk of life-changing complications will be administered the approved vaccine through GPs and approved medical centres.

Pending any issues in production and distribution, other nations could see their first public injections as soon as March 2021.

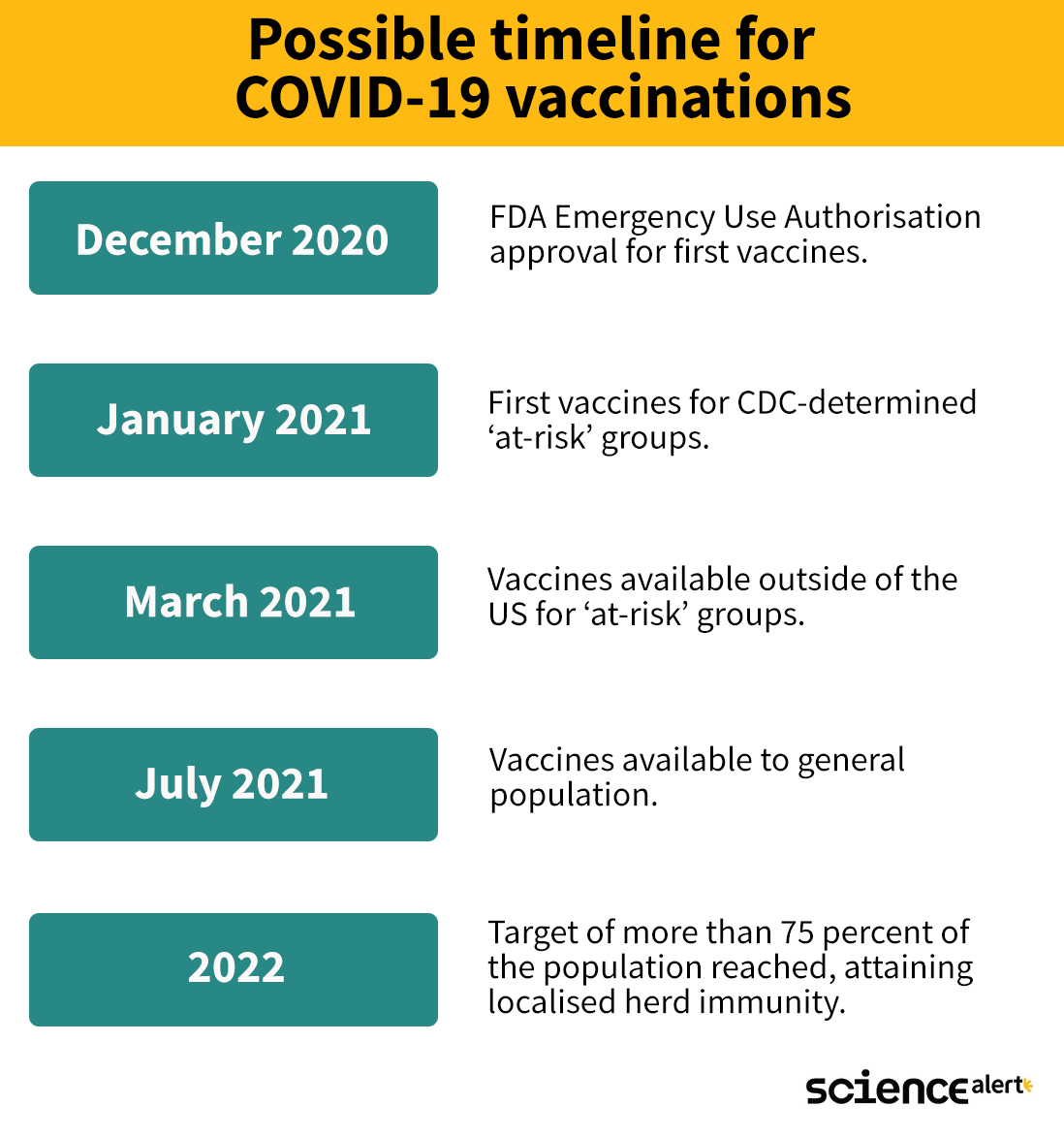

Here is an approximate timeline for what we might expect in coming months:

As promising as it looks, hold onto those masks - this is only what we might expect if everything goes perfectly.

What determines a 'best case scenario'?

The first step in any new medical intervention or treatment is for local authorities to give approval. In the US, this is the responsibility of the Food and Drug Administration. In the UK, it is the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). In Australia it is the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA).

While the process for approving a new vaccine or drug can take months, FDA emergency authorisation can allow for a more immediate resolution in the US. This reduces years of red tape to as little as a couple of weeks, but could still fail to provide approval.

If all goes well, the US federal government's Operation Warp Speed is preparing to have the first doses administered within 24 hours of FDA approval, with a goal to be able to start to deliver 300 million by January 2021.

Unfortunately there are another two major hurdles to overcome - safe and efficient distribution of the vaccine in high enough quantities, and trained staff to administer and track each dose.

The pharmaceutical giant Pfizer is one of two US companies with a promising vaccine in the pipeline. Its mRNA-based vaccine must be kept at -70 degrees Celsius (-94 Fahrenheit) to remain effective, demanding a 'cold chain' from the point of manufacture to the clinic. Not all locations will have the means to keep ample numbers of vaccines this cold for so long.

Moderna is making the other current frontrunner and their vaccine fortunately does not need to remain in deep freeze - the company has announced that the vaccine can last up to a month in a regular fridge.

Even among centres with the means to store the vaccine, resources and doses need to be allocated to where they will do the most good. A Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) advisory group in the US is yet to ethically determine who will receive immunisations from the initial stockpile.

These will most likely be individuals at high risk of catching the illness, who will suffer its effects the most, or who will raise the risk of suffering among others should they become infected. This could include frontline medical workers, the elderly, and those with certain pre-existing conditions.

Both frontrunner vaccines also require two doses to be taken to have the best chances of working. Pfizer's vaccine needs two doses separated by three weeks, and Moderna's vaccine doses are given a month apart.

This means twice the vials, as well as twice the amount of distribution and storage space required, and there's also the issue that not 100 percent of those who get vaccinated will come back in a timely fashion for their second dose.

There's also the likelihood that people could need to continue to take the vaccine at periodic intervals, which puts further pressure on manufacturers.

Pfizer is aiming to have 50 million for distribution in the US by the end of the year, which means roughly 25 million people at risk of COVID-19 could have a chance at protection. By February, around a quarter of the US population could be vaccinated.

By March, Pfizer is expecting to have up to 1.3 billion doses rolling out for global distribution.

When will enough people around the globe be vaccinated for the pandemic to end?

With production ramping up as expected in coming months, healthy members of the US community could expect to have a vaccine available to them by April.

"By the time we get through December, January, February, March, April, we hopefully will have been able to get to the people who are listed as priority people," says the federal government's infectious disease expert, Anthony Fauci.

"I would say starting in April, May, June, July, as we get into the late spring and early summer, that people in the so-called general population, who do not have underlying conditions or other designations that would make them priority, could get them."

Having a vaccine available is one thing. Having enough people receive them is another.

While it's feasible that most developed nations around the world could have access to a vaccine by the second quarter of 2021, delivering it to where it will do most good will become an increasingly difficult task once more accessible parts of the global community are covered.

Current estimates suggest roughly 7 out of 10 people would need to be immune within a community for the virus to be locally eradicated. This is assuming immunity against the novel coronavirus sticks around long enough to be effective, which is still yet to be shown.

So don't get too excited just yet. There's now a plan for hope, but we're still a long way from seeing it through.

All Explainers are determined by fact checkers to be correct and relevant at the time of publishing. Text and images may be altered, removed, or added to as an editorial decision to keep information current.