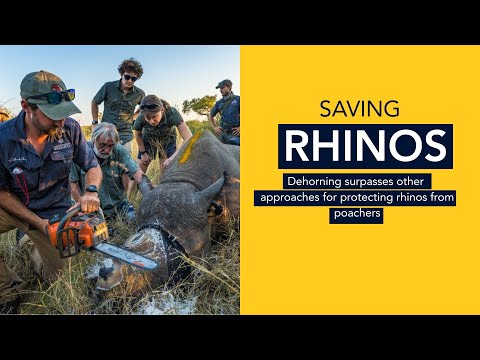

Taking the relatively simple step of trimming the horns of wild rhinoceroses is enough to dramatically reduce the rate at which the animals are killed by poachers.

Across 11 nature reserves in South Africa, scientists found that dehorning black (Diceros bicornis) and white rhino (Ceratotherium simum) populations saw a sudden, sharp reduction in poaching by an average of 78 percent. It was, by far, the most effective method of curtailing the illegal slaughter of these endangered animals, researchers found.

"Dehorning rhinos to reduce incentives for poaching – with 2,284 rhinos dehorned across eight reserves – was found to achieve a 78 percent reduction in poaching, using just 1.2 percent of the overall rhino protection budget," says conservation biologist Tim Kuiper of Nelson Mandela University in South Africa.

The rhino horn trade represents one of the most poignant examples of the destructive influence of human activity.

The horns of these animals are made from keratin, like our own fingernails and hair; yet the perception persists among many cultures that they have medicinal value in spite of a complete lack of scientific evidence. Demand is so high that most rhino species on Earth are now at the brink of extinction due to poaching.

Many different strategies for reducing poaching have been proposed, from 3D printing rhino horns to the death penalty for offenders.

Kuiper and his colleagues conducted their study to determine the efficacy of the measures in place across 11 nature reserves in the Greater Kruger area – a landscape of about 2.4 million hectares wherein roughly 25 percent of all Africa's rhinos currently reside.

The researchers documented the poaching deaths of 1,985 rhinos between 2017 and 2023. That's roughly 6.5 percent of the rhino population of the area.

Most of the investment into anti-poaching measures focuses on reactive strategies – increased ranger presence, cameras, and tracking dogs. In the timeframe the researchers studied, these measures resulted in the arrests of around 700 poachers – but they did not significantly reduce the rate at which rhinos were killed, at least in part because of law enforcement corruption, the researchers say.

However, when dehorning measures were enacted, poaching rates plummeted.

Dehorning does not harm the rhino; it's a bit like having your nails trimmed or your hair cut. The horn's growth plates are left intact, so the keratin gradually regrows over time. Removing the horn removes the incentive to kill the rhino, since the horn is what the poachers want.

When the rhinos were dehorned, not only did the rate of poaching decrease; so too did the rate at which poachers entered the area.

However, dehorning was not a straight prevention measure. Because the horn grows back, 111 rhinos with horn stumps were still killed by poachers. Although the poaching rate of dehorned rhinos was lower, even a horn stump was sufficient incentive at least some of the time for the poaching syndicates.

And while poaching rates were down in the regions where dehorning was active, poachers often moved onto other regions to try their luck elsewhere, evidence suggests.

"It may be best," Kuiper wrote on The Conversation, "to think of dehorning as a very effective but short-term solution that buys us time to address the more ultimate drivers of poaching: horn demand, socio-economic inequality, corruption, and organised criminal networks."

Rhino poaching is such a complex issue that no one solution is likely to fix it. Removing the incentive as a first step, however, seems like it may be an important piece of the broader solution.

"It's important to check that our conservation interventions work as intended, and keep working that way," says ecologist Res Altwegg of the University of Cape Town.

"For me, this project has again highlighted the value of collecting detailed data, both on the interventions that were applied and the outcome. It's such data that makes robust quantitative analyses possible."

The researchers dedicate their work to the late Sharon Haussmann of the Greater Kruger Environmental Protection Foundation, who was instrumental to this collaborative research effort.

The findings have been published in Science Advances.