A plague that swept through Eurasia for 2,000 years – millennia before the Black Death of the Middle Ages – has only ever been detected in human remains, until now. For decades, it has been unclear how the Bronze Age plague spread so widely, but now we know which animal was a likely carrier.

A team of archaeologists sifted through scraps of DNA in the bones and teeth of Bronze Age cattle, goats, and sheep, as part of a large, ongoing study to track how these animals migrated, alongside humans, from the Fertile Crescent in the Middle East across Eurasia.

Such ancient samples of animal DNA are never fully intact, usually quite fragmented, and very contaminated with the leftovers of organisms that inhabited the animal's body in life, and long after death.

Related: Black Death's Carnage Traced to a Volcanic Eruption Half a World Away

"When we test livestock DNA in ancient samples, we get a complex genetic soup of contamination," University of Arkansas archaeologist Taylor Hermes explains.

"This is a large barrier to getting a strong signal for the animal, but it also gives us an opportunity to look for pathogens that infected herds and their handlers."

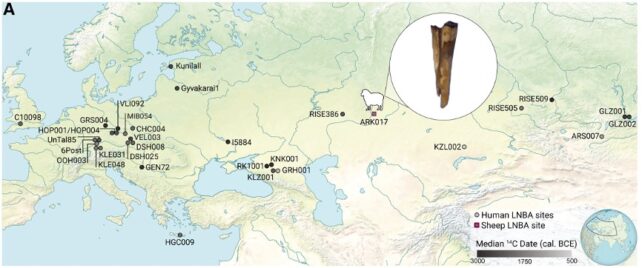

One pathogen Hermes and his colleagues encountered in the remains of a 4,000-year-old domesticated sheep unearthed at Arkaim, an archaeological site in the Southern Ural Mountains of Russia, stopped them in their tracks.

On one tooth was the DNA of the plague bacteria, Yersinia pestis, an ancient strain that was unable to infect fleas, as it did later during the Middle Ages.

Because Y. pestis had yet to figure out how to use fleas as a vector during the Bronze Age, archaeologists have often wondered how the plague spread so widely among humans. We know many humans died from infection, their bodies still containing genetic traces of an identical strain of plague, uncovered at sites thousands of kilometers apart.

This is the first evidence of the Late Neolithic Bronze Age lineage of the bacteria found in a non-human animal, a discovery which the researchers shared in a preprint earlier this year. The research has now been peer reviewed.

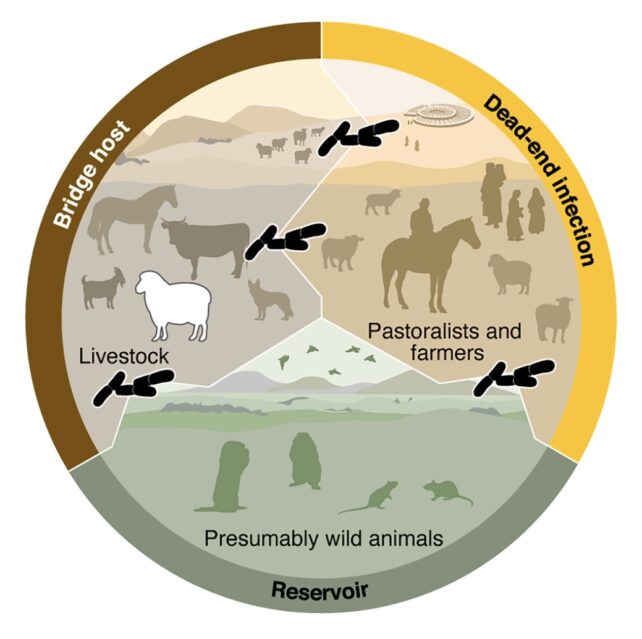

It's easy to imagine how domestic sheep, roaming across the vast grasslands of the Eurasian Steppe, may have encountered a wild animal carrying the bacteria, but not made sick by it, and then spread it between herds and shepherds. However, the team notes they can't rule out human-to-sheep transmission.

"It had to be more than people moving. Our plague sheep gave us a breakthrough," Hermes says.

"We now see it as a dynamic between people, livestock and some still unidentified 'natural reservoir' for it, which could be rodents on the grasslands of the Eurasian steppe or migratory birds."

Tracking down the DNA of ancient pathogens is tricky. People don't bury animals with the same care as they do other humans, so their remains are not usually so well-preserved.

Many specimens of domestic animals that archaeologists find are actually the leftovers of human meals, which means they tend to have been cooked (a sure-fire way to break down the DNA).

Related: The Black Death Shaped Human Evolution, And We're Still in Its Shadow

"Moreover, people tend to avoid consuming visibly sick animals, and therefore faunal assemblages are likely biased toward healthy animals," biologist Ian Light-Maka, of the Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology, Hermes, and their colleagues write in their published paper.

"Even when infected animals are consumed, a single animal may infect many people, and the probability of that specific animal being found and later studied may be low."

This is only the third time that some strain of Y. pestis has ever been found in ancient animals. The first two were a medieval rat and a Neolithic dog; however, those DNA samples were too fragmented to produce reliable results.

The latest find is particularly exciting, Hermes says, because the site where this sheep was found, Arkaim, is a human settlement linked to the Sintashta culture, known for creating impressive bronze weapons, riding horses, and spreading their genes into Central Asia. These people have also been found with traces of the Late Neolithic Bronze Age (LNBA) plague strain.

When this infected sheep lived, the Sintashta were just beginning to expand their livestock herds, since their horse-riding abilities allowed them to cover greater territory quickly, potentially increasing exposure to wild species harboring the plague.

"Nevertheless, it is not possible with a single genome to reconstruct a complete understanding of the ecology of the LNBA lineage across the diverse set of cultures and geographies afflicted by this prehistoric plague lineage, and our results suggest its reservoir remains at large," the authors conclude.

This research is published in Cell.