We're all a little obsessed about aliens. Lonely little Earthlings that we are, science and philosophy are bent on knowing why we're here and whether we're alone.

Until we're the ones doing the probing on something from beyond Proxima Centauri, we have to make do with our imaginations. But with the help of experts in evolutionary biology, we can make some fascinating guesses at what could be out there.

Researchers from the University of Oxford have decided to use their skills in this field to outline an argument for applying natural selection to predicting the morphologies and functions of extra-terrestrial organisms.

"Past approaches in the field of astrobiology have been largely mechanistic, taking what we see on Earth, and what we know about chemistry, geology, and physics to make predictions about aliens," says researcher Sam Levin.

Instead of assuming life forms from other worlds are bound by similar chemical attributes, we should be more focused on naturally selective processes, claims Levin.

"This is a useful approach, because theoretical predictions will apply to aliens that are silicon based, do not have DNA, and breathe nitrogen, for example."

To sketch out the kinds of biology we'd expect to find out there on the kinds of oddball worlds we're discovering, the researchers argue we should gather evidence on any critical planetary moments that could act as an evolutionary trigger.

Evidence is mounting for massive global events on our own planet kickstarting new evolutionary pathways, such as releasing bursts of nutrients.

On Earth, these events have been defining moments on the path of life – the merging of cells to form significant symbiotic partnerships, or the diversification of cells in colonies to represent something more multicellular.

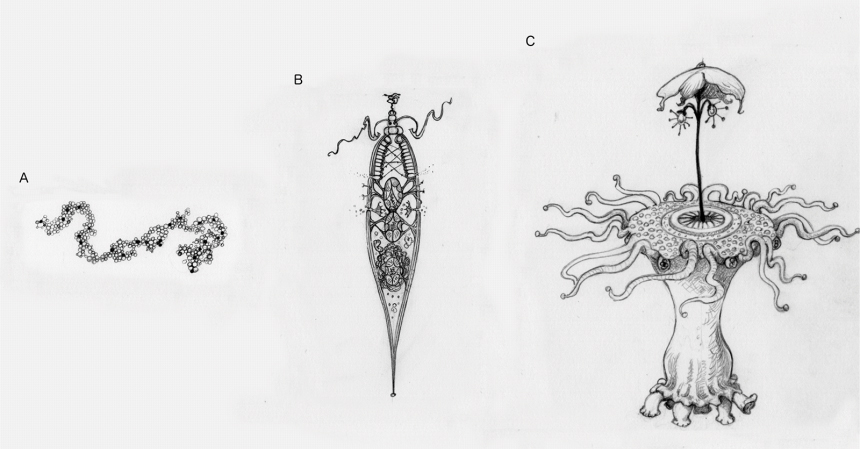

The researchers sketched out some back-of-the-envelope concepts of how complexity might proceed in another biosphere.

Researchers sketch a concept for a very alien evolutionary path in an alien environment. (Helen.S.Cooper)

Researchers sketch a concept for a very alien evolutionary path in an alien environment. (Helen.S.Cooper)

Predicting these steps in complexity might not tell us much about the fine details, but they could still help us flesh out on which worlds we should expect slime and on which we could hope for something more communicative.

"We still can't say whether aliens will walk on two legs or have big green eyes," says Levin. "But we believe evolutionary theory offers a unique additional tool for trying to understand what aliens will be like, and we have shown some examples of the kinds of strong predictions we can make with it."

To be fair, proposing we apply evolution to astrobiology isn't exactly ground-breaking. Or even remotely novel.

But it's clearly a useful exercise in exploring what's possible. Nothing in what we've learned about evolution on Earth suggests it wouldn't work on any type of imperfectly replicating system, after all.

It can even be argued that this feature should form the very basis of how we identify life, meaning if we did discover biology elsewhere it would by definition be a "self-sustained chemical system capable of undergoing Darwinian evolution".

Thinking of it this way, the very concept of discrete alien species might be a red herring. On Earth, the boundaries between individual organisms and our biosphere are often hazy. Likewise, first contact might be less like a handshake with ET and more like dipping a finger into a planet-wide primordial soup.

"At each level of the organism there will be mechanisms in place to eliminate conflict, maintain cooperation, and keep the organism functioning," says Levin. "We can even offer some examples of what these mechanisms will be."

The research paper might not be revolutionary, but acts as a useful reminder of evolution as a defining quality of life. It serves as an interesting touchstone for what we could reasonably expect from biology that evolved on an exoplanet.

Perhaps we could even begin to create some kind of preliminary categories without setting foot on any of these far-flung worlds.

At the very least, it's added fuel for one of humanity's favourite pastimes – dreaming that we're not alone.

This research was published in the International Journal of Astrobiology.