Researchers have trialled an experimental dengue vaccine on a group of volunteers, and have shown that, six months later, 100 percent of them were protected from the virus, even after having dengue directly injected into their system.

Dengue is similar to Zika in that it's spread by Aedes mosquitoes, and is on the verge of reaching epidemic levels in southeast Asia, the Pacific, and the Americas, with more than 390 million people being infected with one of the four dengue strains every single year. This is the first time a vaccine has been shown to prevent infection, and the results are so promising, it's now been rushed through into large-scale phase 3 clinical trials.

"The results of this work are very straightforward and quite conclusive," one of the researchers involved in the trial, Beth Kirkpatrick from the University of Vermont, told The Washington Post. "The bottom line is that the vaccine appears to be 100 percent efficacious."

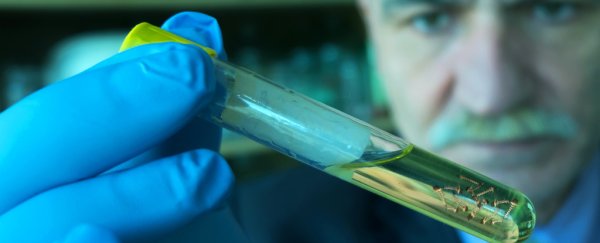

To test the vaccine, researchers led by the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) took a group of 41 volunteers and randomly gave them either a placebo injection, or the experimental dengue vaccine, which contains a harmless live version of the virus.

Six months later, they injected those same participants with a mild form of the dengue virus, and found that all 21 participants who'd received the vaccine were completely protected against infection. Meanwhile, the 20 people in the placebo group had traces of the virus in their blood, and a few developed a rash.

If injecting people with live viruses sounds pretty full-on, that's because it is - challenging participants with live viruses like that is something that fell out of favour centuries ago, and most modern vaccine trials simply look for traces of antibodies the bloodstream to determine immunity.

But scientists have been using that approach unsuccessfully to find a vaccine for dengue for almost 100 years, so this team felt it was time to try something more drastic - all with close medical supervision and in the safest way possible, of course.

Importantly, the strain of dengue they injected volunteers with causes nothing more than a mild rash (and no fever) - something that was important for the patients to be aware of, given the 50/50 chance of becoming infected.

And the risk paid off - the results of the small trial are so exciting that a large-scale phase 3 clinical trial began in Brazil on 22 February, with a target enrolment of 17,000 adults, adolescents, and children. It'll be completed in 2018, so we can expect results some time after that.

But because they've already challenged the vaccine with the live virus, researchers are uncharacteristically optimistic. "Knowing what we know about this new vaccine, we are confident that it is going to work," said lead researcher Anna P. Durbin from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

The science community is also excited about using this same method to improve vaccine research, and weed out which ones are never going to work before spending millions on large trials.

"This is a tremendous step forward, and something that has been desperately needed for 30 years," Duane Gubler, a disease researcher at the Duke NUS Medical School in Singapore, who was not involved in the trial, told Nature. The lack of human challenge studies, he said, has "actually been one of the things that has made the development of dengue vaccines very difficult".

It's important to note that these types of challenge studies "would never be used for certain deadly pathogens, such as Ebola", notes the NIAID.

Excitingly, dengue is in the same family as Zika virus, and the team thinks this research will speed up the development of a Zika vaccine. Challenge trials could also help them better understand how the virus works in humans.

The research has been published in Science Translational Medicine.