Scientists have produced the first human corneas to be 3D-printed in a lab, showing how we could potentially generate this vital bit of anatomy ourselves – and save millions of people from blindness related to corneal damage along the way.

The cornea, the membrane at the front of the eye, is essential in helping us focus properly, while also protecting our eyes from the outside world. When diseases like trachoma take hold, they can be devastating to our vision.

As a result, human corneas are in demand, with around 10 million people worldwide waiting for a transplant to help fix vision problems. Another 5 million people have gone completely blind due to scarring of the cornea.

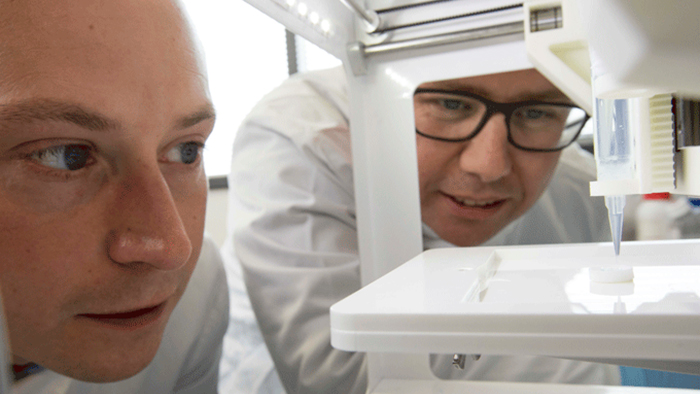

(Newcastle University)

(Newcastle University)

If we can produce usable corneas in the laboratory, then many of these people might be helped, something that the researchers from Newcastle University in the UK explain has been the aim for many scientists for a long time.

"Many teams across the world have been chasing the ideal bio-ink to make this process feasible," says senior researcher Che Connon.

"Now we have a ready to use bio-ink containing stem cells allowing users to start printing tissues without having to worry about growing the cells separately."

The special bio-ink mixes alginate and collagen proteins and has been developed to hit a very specific set of criteria: being stiff enough to hold its shape, and being soft enough to fit through the nozzle of a 3D printer.

The structure also needs to be able to allow the growth of human corneal stromal (connective tissue) cells, taken from a donor.

This proof-of-concept ticked all the boxes: the scientists were able to print out a cornea, as a series of concentric circles, in less than 10 minutes.

Previously, the same team had used a similar hydrogel to keep stem cells alive for weeks at room temperature. Now they've been able to transfer this to a usable cornea, with cells remaining viable at 83 percent after a whole week.

The researchers point out it's likely to be years before this can be perfected and scaled up: as with other attempts to grow human corneas in the lab we've seen in recent years, progress has to be steady and cautious.

That said, it's an amazing first step towards a solution, and could eventually give us an unlimited supply of corneas for transplant, anywhere in the world.

Even better, they can be custom-made to fit each patient, thanks to the 3D printing technology that has also been tested with artificial hearts and other tissue. With a scan of someone's eye, the implant can be designed to the right size and shape.

"Our 3D printed corneas will now have to undergo further testing and it will be several years before we could be in the position where we are using them for transplants," says Connon.

"However, what we have shown is that it is feasible to print corneas using coordinates taken from a patient eye and that this approach has potential to combat the world-wide shortage."

The research has been published in Experimental Eye Research.