A research team led by Caltech may have just discovered the first-ever superkilonova, a cosmic phenomenon in which a star explodes twice in violently different ways.

Their analysis of a series of observations that began with a gravitational wave detected earlier this year may have delivered evidence of the first known supernova to be followed by a kilonova.

Supernovas occur when rapidly spinning stars far more massive than the Sun collapse and explode, typically leaving behind a neutron star.

Related: Scientists Capture The Moment a Supernova Rips Open Its Star, in Stunning First

Kilonovas, on the other hand, are produced by incredibly energetic mergers of two neutron stars, which often start their existence as a binary system. These powerful events send gravitational waves rippling through spacetime, ringing the very fabric of the Universe like a bell.

So when gravitational waves like these were detected by the LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA collaboration on August 18, 2025, astronomers went on the hunt for signs of a cataclysmic collision.

Within hours, the astronomical community scoured the skies for its exact source and spotted an intriguing and rapidly fading object 1.3 billion light-years away.

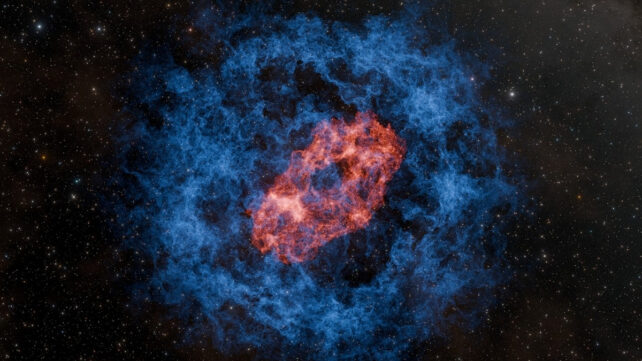

In some ways, this specific event – now known as AT2025ulz – resembled the only other "unambiguously confirmed" kilonova discovered in 2017. Named GW170817, it had been a milestone breakthrough in which scientists first pinpointed the source of gravitational waves and their origin.

As with GWI70817, the glowing embers found at AT2025ulz's location glowed red with the creation of heavy elements like gold, indicating an energetic collision had occurred. Yet after its red glow faded a few days later, AT2025ulz brightened once again, only this time showing hydrogen in its spectra; typical of a supernova rather than a kilonova.

So what was it, a supernova or a kilonova? Both, the researchers suggest.

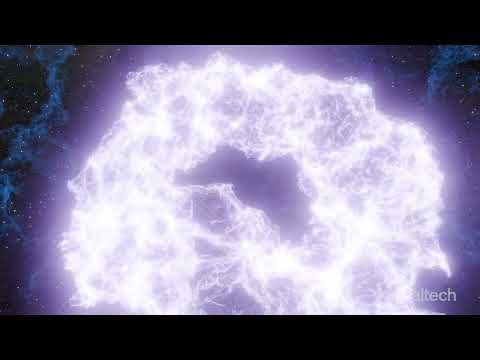

Past studies have hypothesized supernovae may – on rare occasions – deliver two neutron stars from their rapidly spinning disc of debris, rather than just the one. Were they to immediately collide and merge, they might generate the gravitational-wave signal of a kilonova.

Normally, these mergers usually occur in open space, allowing an unobstructed view of their emissions.

Brian Metzger, an astronomer at Columbia University and a study co-author, explained to ScienceAlert via email that this time the merger occurred "within the exploding star, so any kilonova signal would be blocked by the much greater mass ejected from the exploding star."

Equally importantly, the two colliding objects that produced the kilonova included a surprisingly small body – "at least one of the colliding objects is less massive than a typical neutron star," says David Reitze, laser physicist at LIGO and one of the study's co-authors.

That in itself is a rare find, because the formation mechanisms behind such (as-yet undiscovered) sub-stellar neutron stars remain a "major challenge to stellar evolution."

Neutron stars are predicted to have a size limit that's generally between 2.2 and around three solar masses, though in principle they can go as low as 0.1 solar masses.

Theoretically, there are just two ways to make sub-stellar neutron stars from a supernova. Either via fission, as a rapidly spinning massive star goes supernova and splits into two neutron stars instead of one, or by a process called fragmentation.

In the latter scenario, the rapidly spinning massive star (of at least 20 solar masses) collapses to form a large spinning gas disk weighing several solar masses.

Within seconds after forming, the disk fragments under its own gravity into "a swarm of smaller clumps that themselves go on to collapse into low-mass neutron stars, again within seconds," explains Metzger.

The process is similar to how planets form in the disks that surround proto-stars, Metzger told ScienceAlert.

Either way, this still indefinite result is a reminder that the Universe will constantly surprise and confound us with its endless mysteries. It also highlights that such fascinating phenomena may have multiple interpretations hidden in the data.

More research is necessary to confirm the superkilonova and similar events.

"Future kilonovae events may not look like GW170817 and may be mistaken for supernovae," concludes Mansi Kasliwal, astronomer at Caltech and the study's first author.

This research is published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.