Experiments inside a fusion reactor in China have demonstrated a new way to circumvent one of the caps on the density of the superheated plasma swirling inside.

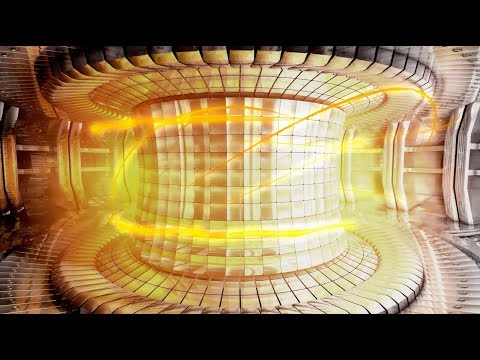

At the Experimental Advanced Superconducting Tokamak (EAST), physicists successfully exceeded what is known as the Greenwald limit, a practical density boundary beyond which plasmas tend to violently destabilize, often damaging reactor components.

For a long time, the Greenwald limit was accepted as a given and incorporated into fusion reactor engineering. The new work shows that precise control over how the plasma is created and interacts with the reactor walls can push it beyond this limit into what physicists call a 'density-free' regime.

Related: Korean Fusion Reactor Sets New Record For Sustaining 100 Million Degree Plasma

Fusion reactors are designed to replicate the intense nuclear fusion that occurs in the heart of the Sun, generating vast amounts of energy. There are a number of significant barriers to overcome – one of which is plasma density.

The rationale is that the more atoms you pack into the plasma, the more they interact, and the more fusion reactions take place, thus increasing the energy output. At the superheated plasma temperatures inside tokamaks – magnet-lined toroidal 'racetracks' along which the plasma is contained and channeled – the energy output generally scales with the plasma density.

This is where the Greenwald limit curtails the fun. It's not a hard law of physics, per se, but rather an observed phenomenon that can be described mathematically to predict how far plasma density can go within a tokamak before it is likely to destabilize and abruptly collapse.

This is because, as the plasma density increases, the plasma radiates more energy, cooling faster at its boundary, especially when atoms from the reactor wall enter the plasma. Energetic plasma particles knock atoms loose from the wall; once inside the plasma, these impurities increase the rate at which energy is radiated away, which further cools the plasma and promotes the release of even more impurities, creating a feedback loop.

The resultant cooling can then degrade the magnetic confinement that keeps the plasma contained, allowing the plasma to escape and rapidly shut down. Because of this, physicists usually operate magnetic fusion reactors below the Greenwald limit, except in experiments designed to test it.

Recently, however, a theoretical study suggested that self-organization in plasma-wall interactions could allow tokamaks to escape the usual Greenwald density constraint, instead operating in what the authors describe as a separate "density-free" regime.

A team led by physicists Ping Zhu of Huazhong University of Science and Technology and Ning Yan of the Chinese Academy of Sciences designed an experiment to take this theory further, based on a simple premise: that the density limit is strongly influenced by the initial plasma-wall interactions as the reactor starts up.

In their experiment, the researchers wanted to see if they could deliberately steer the outcome of this interaction. They carefully controlled the pressure of the fuel gas during tokamak startup and added a burst of heating called electron cyclotron resonance heating.

These changes altered how the plasma interacts with the tokamak walls through a cooler plasma boundary, which dramatically reduced the degree to which wall impurities entered the plasma.

Under this regime, the researchers were able to reach densities up to about 65 percent higher than the tokamak's Greenwald limit.

This doesn't mean that magnetically confined plasmas can now operate with no density limits whatsoever. However, it does show that the Greenwald limit is not a fundamental barrier and that tweaking operational processes could lead to more effective fusion reactors.

The team will be experimenting further with their findings to see how EAST operates under high-performance conditions in the newly described density-free regime.

"The findings suggest a practical and scalable pathway for extending density limits in tokamaks and next-generation burning plasma fusion devices," Zhu says.

The results have been published in Science Advances.