Babies that are just a few months old will learn more from nursery rhymes and other sing-song talk than standard baby babble chat, according to a new study looking at the foundation of language in infants.

That's because their brains learn to process the rhythm of speech first – which helps them start to differentiate between words – long before they can distinguish between the different sounds that make up words, which appears to kick in at about seven months.

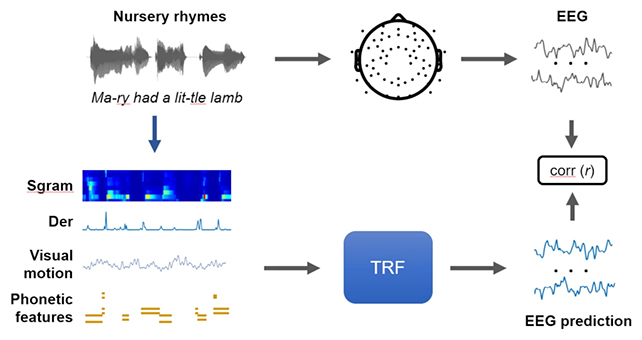

The study used brain imaging to test young babies' reactions to rhythmic information (stressing different syllables and variations in tone) compared to phonetic information (the smallest sound elements of speech, like the sounds 'pa' versus 'ba').

According to the team of researchers from the University of Cambridge in the UK and the University of Dublin in Ireland, the brain scans revealed newborns aren't ready to fully process phonetic information for the first few months of their lives.

"Our research shows that the individual sounds of speech are not processed reliably until around seven months, even though most infants can recognize familiar words like 'bottle' by this point," says neuroscientist Usha Goswami, from the University of Cambridge.

"From then individual speech sounds are still added in very slowly – too slowly to form the basis of language."

Patterns of brain activity were logged in a cohort of 50 babies at four, seven, and eleven months old while they watched a video of a primary school teacher singing nursery rhymes. A custom-made algorithm was then used to analyze the brainwaves to see how these sounds were being interpreted.

The readouts from the brain activity were compared to similar adult scans to see how language understanding was progressing. The researchers found that phonetic encoding emerged gradually, beginning with labial sounds (like the 'b' in baby) and nasal sounds (like the 'm' in mummy).

However, the team observed more consistent responses to the pattern of the nursery rhymes, like melody and the rise and fall of pitch, before the seven month mark. Together with the result of a sister study, this suggests language learning starts with rhythm.

"Infants can use rhythmic information like a scaffold or skeleton to add phonetic information on to," says Goswami.

"For example, they might learn that the rhythm pattern of English words is typically strong-weak, as in 'daddy' or 'mummy', with the stress on the first syllable. They can use this rhythm pattern to guess where one word ends and another begins when listening to natural speech."

Up until now, the general consensus has been that we learn language phonetically, piecing together building blocks to form words, and then sentences, and then carry on from here. But this doesn't fully explain some variations in language development.

This study backs up the idea that rhythm is even more important than phonetics in developing speech, and a particular rhythm – with a strong syllable around two times a second – is something that all languages across the world share.

"Parents should talk and sing to their babies as much as possible or use infant directed speech like nursery rhymes because it will make a difference to language outcome," says Goswami.

The research has been published in Nature Communications.