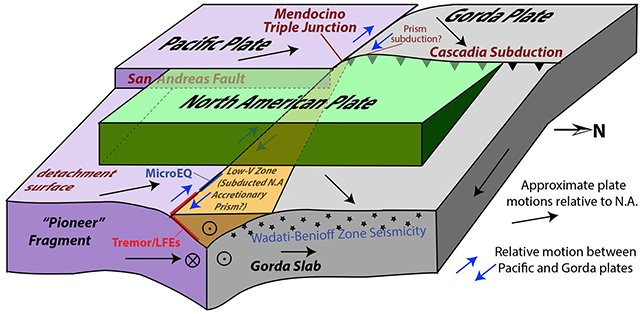

Three huge tectonic plates meet at the Mendocino triple junction off the coast of northern California, and a new study reveals that the underlying geology is significantly more complex than current models show.

US researchers have run a new analysis of small, low-frequency earthquakes recorded by seismometers across the Pacific Northwest, uncovering previously hidden faults.

Their findings show that the triple junction is not composed solely of three plates, but effectively consists of five moving pieces.

Related: Earthquake Sensors Detect Sonic Booms From Incoming Space Junk

That means earthquake prediction models may need to be updated to give experts a better chance of estimating when the next big quake will hit. The discovery is analogous to analyzing the submerged portion of an iceberg, the researchers say.

"You can see a bit at the surface, but you have to figure out what is the configuration underneath," says seismologist David Shelly, from the Geologic Hazards Center run by the United States Geological Survey.

As well as studying data from seismometers – which pick up subtle ground vibrations from very small earthquakes that aren't felt at the surface – the team also verified their field recordings using tidal-sensitivity models.

The push and pull of the tides each day cause small stresses on the underlying rock. By modeling these stresses to test how rocks respond, scientists can check that their interpretation of small, low-frequency earthquakes is correct, which in this case it was.

A chunk of the North American plate has broken off and is being pulled down with the Gorda (Juan de Fuca) plate, the researchers determined. The team also confirmed the previously theorized existence of the Pioneer fragment – a section of older rock being dragged underneath the North American plate.

The North American plate, the Gorda plate, and the Pacific plate make up the Mendocino triple junction, with the Gorda plate being subducted (pushed under) the North American plate, and absorbed into Earth's mantle. Crucially, the subducting surface is not as deep as previously thought.

This research shifts the most likely location of the plate boundary. The model is supported by a 7.2-magnitude earthquake that occurred in California in 1992, which had an origin point at a much shallower depth than contemporary models would have predicted.

"It had been assumed that faults follow the leading edge of the subducting slab, but this example deviates from that," says tectonic geodesist Kathryn Materna, from the University of Colorado Boulder.

"The plate boundary seems not to be where we thought it was."

Related: 'Megathrust' Earthquake Could Trigger San Andreas Fault, Scientists Warn

Accuracy is crucial for predicting earthquakes, and that's where this study will be most useful. Both the San Andreas fault (where the North American and Pacific plates meet) and the Cascadia subduction zone (where the Gorda and North American plates meet) can produce devastating earthquakes.

There are a lot of moving parts to consider with the tectonic faults and earthquake zones of California and the western US seaboard, and scientists are working to get the most comprehensive picture of them – so we can be as prepared as possible for what the ground is likely to do next.

"If we don't understand the underlying tectonic processes, it's hard to predict the seismic hazard," says geophysicist Amanda Thomas, from the University of California, Davis.

The research has been published in Science.