A newly identified link between two notorious geologic zones suggests a major earthquake at one site could trigger another huge quake at the other, creating a double-whammy of destruction.

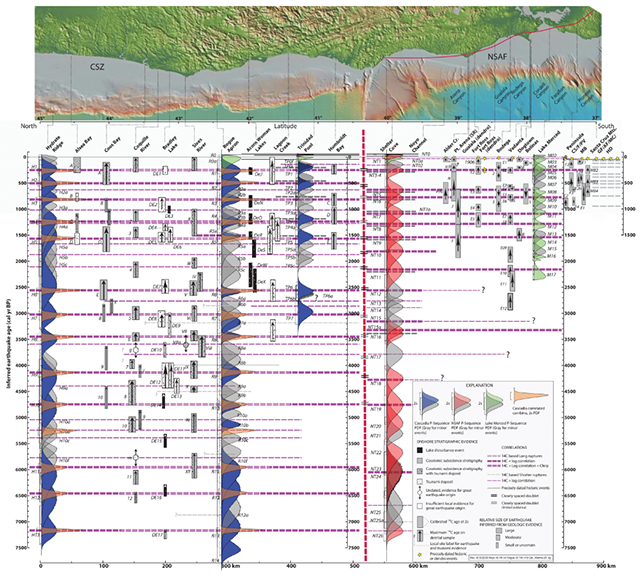

Researchers led by a team from Oregon State University analyzed 137 different sediment cores collected from the Cascadia subduction zone, in the Pacific Northwest, and the northern San Andreas Fault, in California. In those samples, collected on five voyages, they found evidence of synchronized earthquakes at the two sites going back some 3,000 years.

That evidence appeared in the form of turbidites: layered deposits that show up in cores when fast-moving landslides happen underwater, indicated by smaller grains on top and coarser grains underneath. In several cases, the timing of when these turbidites were deposited matched up between Cascadia and San Andreas.

Related: Giant Earthquake Off Russian Coast Triggers Mass Evacuations as Far as Hawaii

Based on these pairings, and the history of earthquakes in both areas, the researchers suggest that a magnitude 9 (M9) earthquake or 'megathrust' along the Cascadia subduction zone could be enough to seriously unsettle the San Andreas Fault too.

"It's kind of hard to exaggerate what a M9 earthquake would be like in the Pacific Northwest," says paleoseismologist Chris Goldfinger, from Oregon State University. "And so the possibility that a San Andreas earthquake would follow, it's movie territory."

At the Cascadia subduction zone, the Juan de Fuca and Gorda plates are sliding underneath the North American plate. The zone is roughly 1,000 kilometers (621 miles) long, and the most recent known megathrust that happened here hit some 325 years ago, at the start of 1700.

Down in California, the San Andreas Fault marks the boundary where the North American and Pacific plates are sliding past each other and building up friction – across a distance of around 1,200 kilometers (nearly 750 miles). The last serious earthquake here was the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake.

Links between earthquakes in the two regions have been suggested before, but that was a hypothesis based on limited data, with a greater margin of error.

Here, the evidence is more conclusive, sparked by the collection of one particular sediment core that was only drilled after a navigation blunder that sent the researchers further south than they had intended.

That core, picked up in the Noyo Canyon off the California coast, on the San Andreas side of the boundary between the two zones, showed signs of a dual earthquake event in both locations, and led the researchers to look for similar patterns more widely.

"A lightbulb went on and we realized that the Noyo channel was probably recording Cascadia earthquakes, and that at a similar distance, Cascadia sites were probably recording San Andreas earthquakes," says Goldfinger.

These are two of the most well-known earthquake zones on the planet, and the idea that they could connect with each other – given a large enough initial event – is vital for modeling and hazard planning. We might be talking about an earthquake shaking the entire US Pacific coast.

While the focus of the study is the Cascadia subduction zone triggering the San Andreas Fault, the researchers do leave open the possibility that the triggering could happen in the other direction too, which is another avenue that future studies can explore.

"I'm from the Bay Area originally," says Goldfinger. "If I were in my hometown of Palo Alto, and Cascadia went off, I think I would drive east. There looks to me like a very high risk [that] the San Andreas would go off next."

The research has been published in Geosphere.