A new study identifies an extreme but effective way that brain immune cells can prevent the parasite Toxoplasma gondii from spreading: they kill themselves to eliminate the dangerous microbes they carry.

The discovery comes from researchers at the University of Virginia in the US, whose tests on lab mice showed that important brain defenders called T cells would mark themselves for programmed cell death if they became infected with T. gondii.

T. gondii usually sets up shop inside neurons, but the researchers suggest that the parasite may hitch a ride inside T cells to create a kind of Trojan horse – enabling it to spread further. That's when the infected immune cells take drastic action.

"We know that T cells are really important for combating Toxoplasma gondii, and we thought we knew all the reasons why," says neuroscientist Tajie Harris.

"T cells can destroy infected cells or cue other cells to destroy the parasite. We found that these very T cells can get infected, and, if they do, they can opt to die. Toxoplasma parasites need to live inside cells, so the host cell dying is game over for the parasite."

In their studies, the researchers identified a crucial enzyme in the self-destruction process called caspase-8. While caspase-8 was already known to be important to the immune system and cell death, its role here – specifically in cells known as CD8+ T cells – hadn't been seen before.

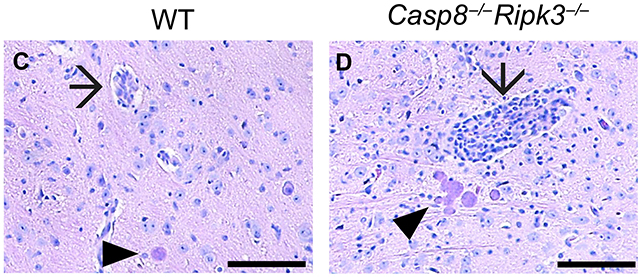

The researchers engineered mice without caspase-8 in various brain and immune cells, and found thatT. gondii infections spread extensively to the brain only when CD8+ T cells lacked caspase-8.

This was despite strong immune system responses from both the mice with caspase-8, and those without it. The bodies of all of the animals were still working hard to fight off the infection, but some lacked a vital defensive mechanism.

The research can tell us more about infection and disease more generally, too. It's rare that T. gondii actually attempts this T cell trick– and that's quite possibly because of the self-destruct mechanism that caspase-8 manages. For pathogens to survive, they need to interfere with caspase-8 somehow.

"Prior to our study, we had no idea that caspase-8 was so important for protecting the brain from Toxoplasma," says Harris.

"Now, we think we know why. Caspase-8 leads to T cell death. The only pathogens that can live in CD8+ T cells have developed ways to mess with Caspase-8 function."

T. gondii can infect all warm-blooded animals and is fatal in some cases. It's often passed on to humans by cats, but we can also get it by eating undercooked meat or other contaminated foodstuffs.

Amazingly, it can sit dormant in our brains without causing any harm or triggering any symptoms – up to 40 million people in the US alone are thought to have toxoplasmosis (which T. gondii causes). If and when signs of infection do appear, they can include aches and pains, and flu-like symptoms such as a high temperature.

Most people won't know they've got toxoplasmosis and will recover on their own, and this study gives us a good idea why. However, the parasite can cause problems for those who are pregnant or who have a weakened immune system – if they're undergoing chemotherapy, for example.

Improved toxoplasmosis treatments could be developed based on this new information, although we've only seen its effects in mice so far. More broadly, scientists now have a better understanding of the function of CD8+ T cells in immune responses, and other related discoveries may follow.

Related: Scientists May Have Discovered a Way to Rejuvenate The Immune System

"Understanding how the immune system fights Toxoplasma is important for several reasons," says Harris.

"People with compromised immune systems are vulnerable to this infection, and now we have a better understanding of why and how we can help patients fight this infection."

The research has been published in Science Advances.