Where the heck are all the aliens? According to a pair of psychologists, it might be us, not them - we could be missing obvious signs of non-terrestrial civilisations out there.

Being a human is weird. There's so much information our brains need to process for us to function in the world, sometimes we downright miss what's right in front of us.

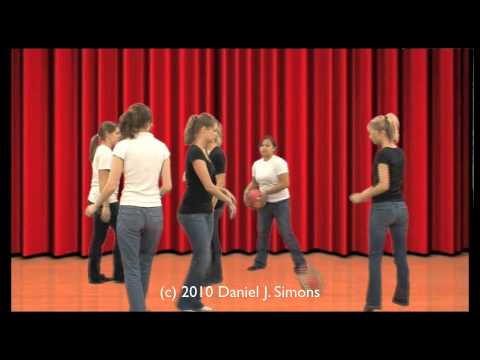

This concept is called 'inattentional blindness', and it's one of the most famous quirks cognitive scientists have ever discovered - not least because it's strikingly easy to demonstrate in a video, as you can watch below:

As Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris from Harvard University poignantly demonstrated in 1999, if your attention is focussed on a task, you can miss pretty dramatic things - even a woman in a gorilla suit casually strolling through a room full of people that you are actively watching.

Inspired by this well-known quirk, a pair of psychologists from the University of Cádiz in Spain used a version of this gorilla test to explore why scientists still haven't found any signs of intelligent alien life.

"What if human factors or biopsychological aspects are biasing this scientific task?" Gabriel de la Torre and Manuel Garcia ask in their new paper.

To test out their idea, the pair tested 137 participants on their cognitive abilities, using a three-question test that helps indicate whether a person is prone to quick answers without reflecting on them (known as 'system 1'), or takes time to consciously think things through ('system 2').

After completing this test along with a questionnaire that measured the subjects' attentiveness, they were asked to visually scan aerial photos of our planet, looking for either artificial structures like buildings, or natural elements, such as rivers and mountain ranges.

(De la Torre & Garcia, 2018)

(De la Torre & Garcia, 2018)

That's where the gorilla comes in - one of pictures had a tiny, 3mm tall gorilla. The researchers predicted that 'system 2' thinkers would be better at spotting the hidden figure, but that didn't turn out to be the case.

Only 32.8 percent of the participants noticed the gorilla at all, and nearly all of them turned out to possess the 'system 1' cognitive style, meaning they were "more impulsive/intuitive individuals", according to the researchers.

"It seems that being centered in a determined search task, eg searching for radio signals of extraterrestrial origin, may blind us from other possibilities," the team concludes.

"We may even miss the gorilla in the task. The question here is how many gorillas we may have already missed in our search for ETI or NTI signs?"

On top of reminding astronomers about inattentional blindness, the psychologists also use their paper to propose a new classification of intelligent alien civilisations.

Derived from the famous expanded Kardashev scale, theirs too ranges from ephemeral, short-lived alien worlds to extremely Star Trekky options that possess "multidimensional travel and dark matter mastery capabilities."

While this study certainly doesn't give us any new methods for detecting non-terrestrial life forms, it's fun to think about the 'space gorilla' preventing us from possibly meeting aliens - although astronomers, rather than psychologists, are still the ones more likely to find life out there.

And, of course, there could be plenty of other explanations for why humanity is still waiting for its first contact. It could just be a matter of time.

The aliens could be too small and microbial to be sending any signals our way, and so far our space probes don't appear to have met any microbes, either.

Or, there could be intelligent aliens out there actively avoiding us.

Or, they could already be dead.

Some scientists even think we should ignore aliens even if they do message us, because they could send some cosmic malware our way. (As if the threat of spam mail ever stopped humans from exploring.)

But either way, keeping on top of our cognitive shortcomings is certainly going to be helpful while we scan the stars for life born elsewhere in the Universe.

The paper was published in Acta Astronautica.