Every now and again, a stellar object is caught zooming across space like a white rabbit, extremely late for a very important date.

Now, for the first time, astronomers have confirmed a supermassive black hole at least 10 million times the mass of the Sun, somehow yeeted from its host galaxy at a jaw-dropping 954 kilometers (593 miles) per second – that's 0.32 percent of the speed of light.

It's not the fastest runaway stellar object ever observed, but the sheer power behind the gravitational kick required to send a black hole of that mass tearing away that fast through the circumgalactic medium just absolutely boggles the mind.

Related: We Have a New Record For The Fastest Star Zooming Around a Supermassive Black Hole

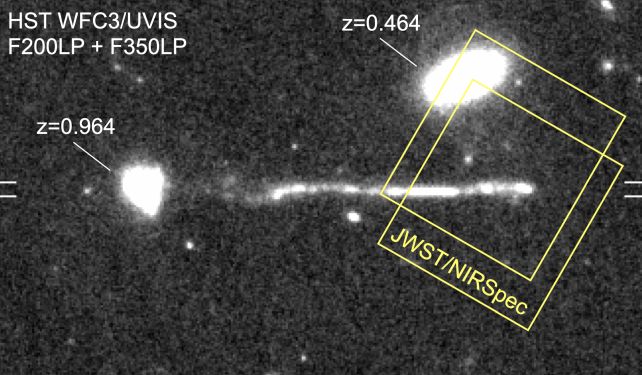

The black hole, now named RBH-1, was first reported in 2023 – a massive object at a light travel time of 7.5 billion years, screaming across space, with an enormous bow shock in front of it and a trail of star formation extending for 200,000 light-years behind it.

At the time, the clues seemed to paint a clear picture of a runaway. Now it's been confirmed in follow-up observations, led by astrophysicist Pieter van Dokkum of Yale University and using JWST's near-infrared NIRSpec instrument. RBH-1 is indeed rocketing through the very outer edges of its galaxy, towards intergalactic space.

How it happened is possibly even more exciting. The researchers believe that the event that gave RBH-1 its kick across spacetime was most likely the gravitational recoil from a supermassive black hole merger.

"These results," they write in a preprint uploaded to arXiv, "confirm that the wake is powered by a supersonic runaway supermassive black hole, a long-predicted consequence of gravitational-wave recoil or multi-body ejection from galactic nuclei."

Supermassive black holes tend to go together like spiders and their webs. Galaxies assemble and grow around black holes, their evolutions shaped by the gravity and behavior of the giant nuclear black holes at their centers.

That doesn't mean that the black hole has to stay put. According to theory, a large enough disruption can dislodge the black hole and send it out to wander the Universe, accompanied only by the small cloud of material within its immediate, inexorable grasp.

Astronomers have gathered plenty of evidence of this mechanism over the years. That includes multiple candidate runaway supermassive black holes ejected from the centers of their galaxies, a galaxy with a second supermassive black hole at its outskirts, and even one galaxy that appears to be missing its supermassive black hole altogether.

Simulations also suggest that there should be quite a large number of rogue supermassive black holes out there, invisibly lurking in the darkness of intergalactic space.

To confirm whether RBH-1 is indeed what it appeared to be in the initial observations, van Dokkum and his colleagues used JWST to map the velocity distribution across the bow shock in front of the black hole as it punches into, and compresses, the circumgalactic medium – the tenuous gas and dust surrounding the host galaxy.

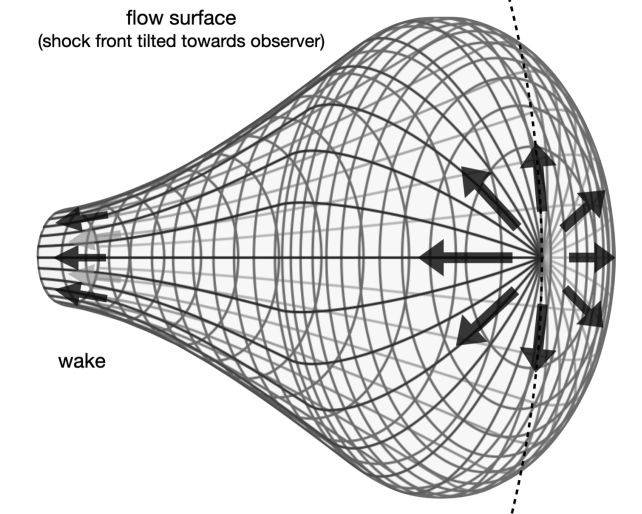

Basically, the entire structure – the bow shock, the black hole, and the star-forming trail behind – is slightly tilted towards us, with the black hole closer and the trail more distant. This coincidence of orientation allowed the researchers to measure light from the shock-heated gas in the bow shock.

When something is moving towards us, the wavelength of its light is slightly compressed towards the bluer end of the spectrum – a phenomenon known as blueshift. The researchers measured the blueshift in front of and behind the bow shock and found a dramatic, abrupt velocity difference.

The material behind the shock front is moving 600 kilometers per second faster than the material in front of it, with only a thin distance between them. They also found that the gas around the outside edges of the bow shock is redshifted as it streams away from us.

This overall structure, the researchers found, can only be created by a high-speed, massive object surging ahead at around 954 kilometers per second.

The next question is: How the heck does this happen? In their discovery paper, the researchers proposed that the mechanism was likely a three-body gravitational interaction between three supermassive black holes, brought together by galaxy mergers.

Related: Black Hole 'UFO' Caught at Critical Moment in Scientific First

With more accurate measurements in hand, they now believe that the most likely explanation is a merger between two supermassive black holes that came together after their host galaxies merged. As they mooshed together to form one supermassive black hole, the asymmetrical release of gravitational energy would have imparted a recoil kick that sent the newly formed black hole flying.

The measured velocity of RBH-1 and the mass of the galaxy it left behind are entirely consistent with models of this process.

"We dub the object RBH-1, recognizing that it is the first confirmed runaway supermassive black hole," the researchers write.

"RBH-1 is empirical validation of the 50-year-old prediction that SMBHs can escape from their host galaxies, through gravitational wave recoil or a three-body interaction."

The paper is available on preprint server arXiv.