Thousands of meters underground, in the chthonic depths of Earth's crust, scientists have at long last caught solar neutrinos in the act of transforming carbon-13 into nitrogen-13.

It's the first time this rare neutrino-mediated nuclear reaction has ever been seen, revealing how some of the most elusive and intangible particles in the Universe can nevertheless quietly reshape matter, down in the subterranean dark far from the surface.

"This discovery uses the natural abundance of carbon-13 within the experiment's liquid scintillator to measure a specific, rare interaction," says physicist Christine Kraus of SNOLAB, the neutrino observatory in Canada where the detection was made.

"To our knowledge, these results represent the lowest energy observation of neutrino interactions on carbon-13 nuclei to date and provide the first direct cross-section measurement for this specific nuclear reaction to the ground state of the resulting nitrogen-13 nucleus."

Related: It's Official: 'Ghost Particle' That Smashed Into Earth Breaks Records

Neutrinos are among the most abundant particles out there in the big, wide Universe. They form in energetic circumstances, such as supernova explosions and the atomic fusion that takes place in the hearts of stars – so they're pretty much everywhere.

However, they have no electric charge, their mass is almost zero, and they barely interact with other particles they encounter. Hundreds of billions of neutrinos are streaming through your body right now, just passing on through like ghosts. That's the reason they're affectionately known as ghost particles.

But every now and again, a neutrino does actually smack into another particle – a collision that produces an infinitesimally faint glow and a shower of other particles. However, they're hard to spot at Earth's surface, where cosmic rays and background radiation obscure the signal.

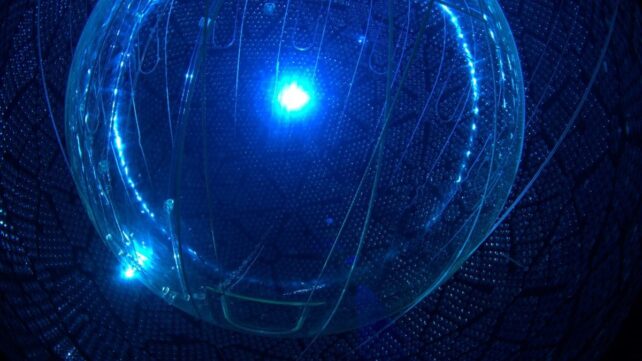

That's why some of the best neutrino detectors are deep underground, where Earth's crust itself serves as a radiation shield. There, giant chambers are lined with photodetectors and filled with a liquid scintillator that amplifies the tiny signals generated by rare neutrino interactions, blooming in the complete, silent darkness.

Neutrinos forged in the heart of the Sun are constantly streaming through Earth. Their energies fall within a well-known range that makes them straightforward to distinguish from atmospheric and astrophysical neutrinos, which are far more energetic and far less common. At the 2-kilometer (1.24-mile) depth of SNOLAB's SNO+ detector, nearly all events in this energy band are solar in origin.

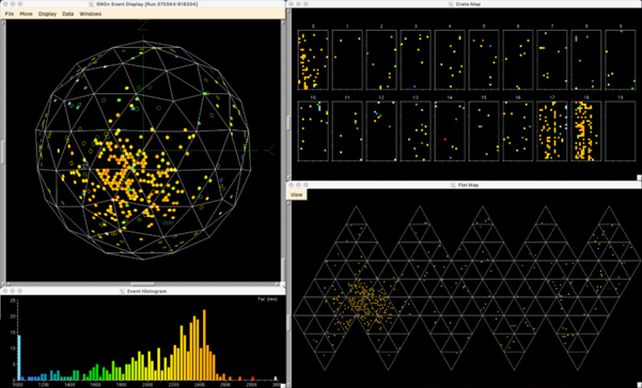

Led by physicist Gulliver Milton of the University of Oxford in the UK, the research team pored over SNO+ data collected between 4 May 2022 and 29 June 2023, looking for a specific signal indicating a neutrino interaction with carbon-13 within the scintillator fluid.

When a solar electron neutrino strikes a carbon-13 nucleus, the collision does two things. The first is the production of an electron, a particle with a negative charge, as the atomic nucleus absorbs the neutrino.

Inside the carbon atom's nucleus are 13 particles: six positively charged protons and seven neutral neutrons. The weak interaction triggered by the neutrino converts one of those neutrons into a proton, emitting an electron.

With its proton count increased from six to seven, the atom is no longer carbon but nitrogen-13, which has seven protons and six neutrons.

About 10 minutes later, the resulting nitrogen-13 – an unstable radioactive isotope of nitrogen with a half-life of, you guessed it, 10 minutes – decays, emitting a telltale anti-electron, or positron.

The result of the interaction from start to finish is a distinctive two-step flash known as a delayed coincidence. Essentially, the researchers can watch for an electron followed by a positron 10 minutes later, as a signature of a neutrino converting carbon-13 to nitrogen-13.

From 231 days of observation data, the researchers identified 60 candidate events. Passing their candidate event data through their statistical model estimated 5.6 neutrino-driven carbon-nitrogen transmutations. That's actually pretty close to the estimated 4.7 events they expected to find.

"Capturing this interaction is an extraordinary achievement," Milton says. "Despite the rarity of the carbon isotope, we were able to observe its interaction with neutrinos, which were born in the Sun's core and travelled vast distances to reach our detector."

The result is exciting. Confirming theoretical predictions is always gratifying, because it means that the science is on the right track.

It also gives a new measurement of the probability of this specific low-energy neutrino-carbon reaction. That means it sets a new benchmark for nuclear physics that will be useful in future studies.

"Solar neutrinos themselves have been an intriguing subject of study for many years, and the measurements of these by our predecessor experiment, SNO, led to the 2015 Nobel Prize in physics," says physicist Steven Biller of the University of Oxford.

"It is remarkable that our understanding of neutrinos from the Sun has advanced so much that we can now use them for the first time as a 'test beam' to study other kinds of rare atomic reactions!"

The research has been published in Physical Review Letters.