Whether it's robots working in a disaster area, autonomous cars getting around town, or satellites peering down through space, having machines that can see through clouds, haze and fog is incredibly useful – and scientists may have just made the best system yet.

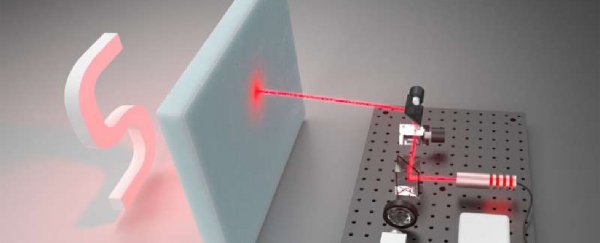

The newly developed system works via an algorithm that measures the movement of individual light particles or photons, as fired in fast pulses from a laser, and uses them to reconstruct objects that are obscured or hidden from the human eye.

What makes the technique extra special is the way that it can reconstruct light that's been scattered and bounced around by the barrier in the way.

In experiments, the laser sight was able to see objects hidden behind a 1-inch layer of foam.

(Stanford Computational Imaging Lab)

(Stanford Computational Imaging Lab)

"A lot of imaging techniques make images look a little bit better, a little bit less noisy, but this is really something where we make the invisible visible," says electrical engineer Gordon Wetzstein, from Stanford University.

"This is really pushing the frontier of what may be possible with any kind of sensing system. It's like superhuman vision."

As the laser light passes through the barrier – the foam, in this study – only a few photons hit the object behind, and even fewer make it back again. However, the algorithm is smart enough to use those little bits of information to reconstruct the hidden object.

Officially, it's known as confocal diffuse tomography, and while it's not the first method of looking through barriers like this, it does offer several improvements – it can work without knowing how far away the hidden object is, for example.

The system is also able to work without relying on ballistic photons, as other approaches do – these are photons that are able to travel to and from the hidden object through a scattering field, but without being distorted themselves.

"We were interested in being able to image through scattering media without these assumptions and to collect all the photons that have been scattered to reconstruct the image," says electrical engineer David Lindell, from Stanford University.

"This makes our system especially useful for large-scale applications, where there would be very few ballistic photons."

Large-scale applications such as navigating a self-driving car in heavy rain, for example, or even capturing images of the surface of Earth (or other planets) through cloud haze – there are a lot of potential uses here. The researchers are keen to keep experimenting with more scenarios and more scattering environments.

Current systems aren't particularly good at dealing with the scattering of light caused by fog and haze.

LiDAR, for example, is brilliant at detecting objects the human eye can't see, but starts to have trouble when rain or fog interferes with its detailed laser scans. Further down the line, this system could fix that problem.

Before we get ahead of ourselves, it's worth noting that scans using this method can take anywhere from a minute to an hour, so there's plenty of optimisation to work on yet.

That said, recreating a hidden object in three dimensions that the human eye can't see is a hugely impressive feat.

"We're excited to push this further with other types of scattering geometries," says Lindell.

"So, not just objects hidden behind a thick slab of material but objects that are embedded in densely scattering material, which would be like seeing an object that's surrounded by fog."

The research has been published in Nature Communications.