Potentially harmful DNA mutations can amass in men's sperm as they age, new research has found, which may in turn impact the number of mutations passed on to children – and the risks of disease in the next generation.

Mutations occur in DNA when cells replicate, and arise either by random chance or because of environmental stresses. They can impact how well the body works, or have no observable effect at all. Mutations accumulate as time goes by, just like wear and tear on a car – but it hasn't been clear how much these genetic mishaps affect sperm in older men.

Researchers from the Wellcome Sanger Institute and King's College London in the UK used a new high-resolution analysis technique called NanoSeq to look in detail at mutations in the sperm of men aged 24-75 years, and the genes those mutations affected.

Related: Sperm Could Be a Bigger Factor in Miscarriages Than We've Been Led to Believe

Not only do mutations occur at higher rates in older men, the data showed, but some are 'selfish' – giving the cells that carry them a growth advantage, so they replicate faster than or outlast other cells in the testes and gradually take over. Many of these mutations have previously been linked to developmental disorders and cancers.

"We expected to find some evidence of selection shaping mutations in sperm," says geneticist Matthew Neville, from the Wellcome Sanger Institute.

"What surprised us was just how much it drives up the number of sperm carrying mutations linked to serious diseases."

The researchers analyzed 81 sperm samples from 57 healthy men, some of whom were twins – a factor which helps separate the effects of age on sperm DNA mutations from inherited genetics.

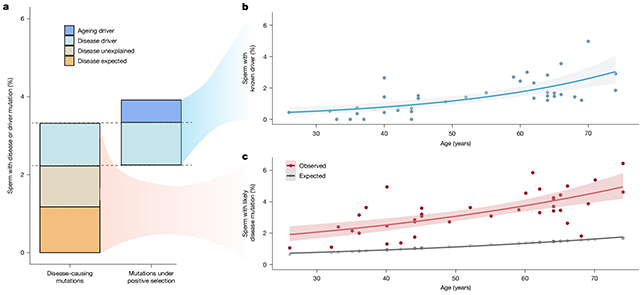

Around 2 percent of sperm from men in their 30s were found to be carrying disease-causing mutations, which jumped up to 3-5 percent for middle-aged and older men (over the age of 43). By age 70, an average of 4.5 percent of sperm had potentially harmful mutations.

The team was also able to identify 40 genes affected by the 'selfish' mutant cells winning out in the positive selection competition in the testes. That will help in future research linking specific mutations to specific disease risks.

"Some changes in DNA not only survive but thrive within the testes, meaning that fathers who conceive later in life may unknowingly have a higher risk of passing on a harmful mutation to their children," says geneticist Matt Hurles, from the Wellcome Sanger Institute.

It's worth bearing in mind that not all of these mutations will necessarily be passed on to the next generation. Some of them may actually reduce the chances of reproduction in some way – by interfering with embryo development, for example.

More work is required to figure out exactly how this steady increase in DNA mutations in men actually affects the health of their kids, but for now, we have a much better idea of the processes involved.

These findings also give scientists a much closer look at the chain of cells that are known as the male germline, cells set aside for the job of passing on genetic material to the next generation – potentially with both positive and negative consequences.

"The male germline is a dynamic environment where natural selection can favor harmful mutations, sometimes with consequences for the next generation," says geneticist Raheleh Rahbari, from the Wellcome Sanger Institute.

The research has been published in Nature.