The effects of exercise would not be nearly as powerful without the input of the brain, according to new research.

A study on mice has found a critical signal in the central nervous system that helps build physical endurance in the wider body after repeated exercise.

Traditionally, scientists thought that our body's extensive response to frequent exercise occurred mainly in the periphery, such as the bones and muscles, and the heart.

But researchers in the US, led by experts at the University of Pennsylvania, think that the brain is key to remodeling our bodies for great physical activity.

Their evidence among mice suggests that specific signals in the central nervous system are "enhancing exercise endurance and coordinating peripheral metabolic adaptations."

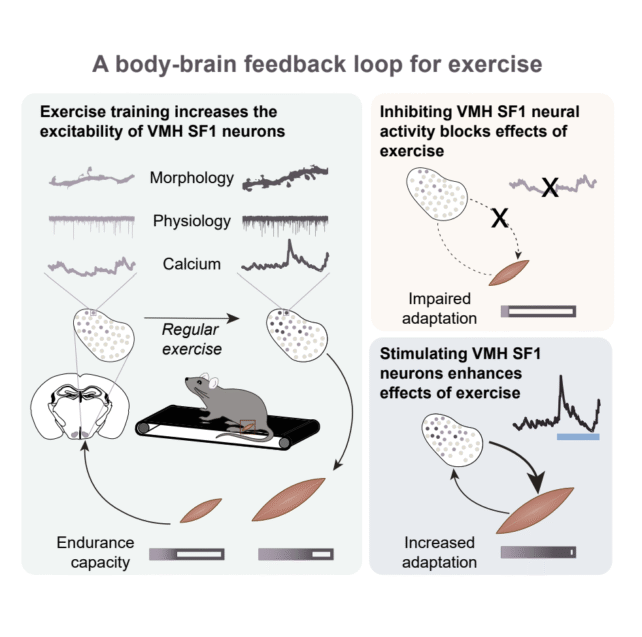

In their experiments, mice that had run on a treadmill showed increased activity within neurons located in their ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH). This part of the brain is involved in balancing the body's energy expenditure against its needs.

The neurons that were most active following exercise, called steroidogenic factor-1 (SF1) neurons, remained so for at least an hour after the mice had finished running.

After 3 weeks of training, running 5 days a week, mice could exercise longer and faster without getting as exhausted. Signals from their SF1 neurons were also elevated compared to the beginning of the trial.

Importantly, when SF1 neuron activity was blocked in some mice, it prevented the same endurance gains. But when the SF1 neurons were artificially activated, it enhanced endurance performance.

Taken together, these results suggest a potent role for SF1 neuron activity in controlling the body's response to repeated exercise and increasing endurance capacity.

"When we lift weights, we think we are just building muscle," says biologist J. Nicholas Betley of the University of Pennsylvania.

"It turns out we might be building up our brain when we exercise."

Emerging evidence suggests that exercise can do far more than just build muscle and burn fat. Short bouts of regular physical activity may boost brain function and may even make your central nervous system look younger.

The effects of exercise on the brain are often considered separately from the effects on the body, but in reality, they are not so easily disentangled.

The new research from Betley and colleagues adds to the idea that exercise bridges the body and the brain, providing potentially powerful treatment for mental health issues like depression.

"A lot of people say they feel sharper and their minds are clearer after exercise," says Betley of the University of Pennsylvania.

"So we wanted to understand what happens in the brain after exercise and how those changes influence the effects of exercise."

Related: Brain Boost Linked to Exercise Can Last Several Years, Scientists Find

Neurons in the brain's VMH are known to integrate signals from the body, such as insulin and glucose levels, to regulate energy expenditure. Without these neurons, mice cannot engage the appropriate energy stores or properly remodel their skeletal-muscular systems during exercise.

After repeated physical activity, the VMH neurons in mice showed nearly double the density of dendritic spines. These finger-like projections allow messages to be received from other brain cells. Perhaps the more information they have, the better they are at controlling the body's energy balance.

Further research in humans is now needed to determine whether VMH neurons in our own species show similar changes after exercise.

The study was published in Neuron.