Alongside better sleep, improved weight regulation, and extended lifespan – and a range of other physical and mental health benefits – we might be able to add a more youthful brain profile as a reason to exercise.

In a new 12-month clinical trial of 130 healthy adults aged between 26 and 58, researchers from the US found that participants who followed a comprehensive weekly exercise regimen ended up with brains that showed signs of being biologically younger than those of a control group.

When scientists talk about biological aging, in simple terms it means the wear-and-tear associated with getting older. While all of us celebrate one birthday every year, different parts of our bodies can be wearing out faster than others.

Related: Scientists Identify Brain Waves That Define The Limits of 'You'

A younger brain potentially means being able to hang on to our full cognitive faculties for longer, as well as a greater resilience to conditions such as dementia – though long-term effects weren't assessed by this study.

"We found that a simple, guideline-based exercise program can make the brain look measurably younger over just 12 months," says data scientist Lu Wan, from the AdventHealth Research Institute.

"These absolute changes were modest, but even a one-year shift in brain age could matter over the course of decades."

The volunteers in the exercise group were asked to meet the recommended weekly exercise guidelines set by the World Health Organization: around 150 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous exercise, which is anything that significantly raises your heart rate and breathing speed.

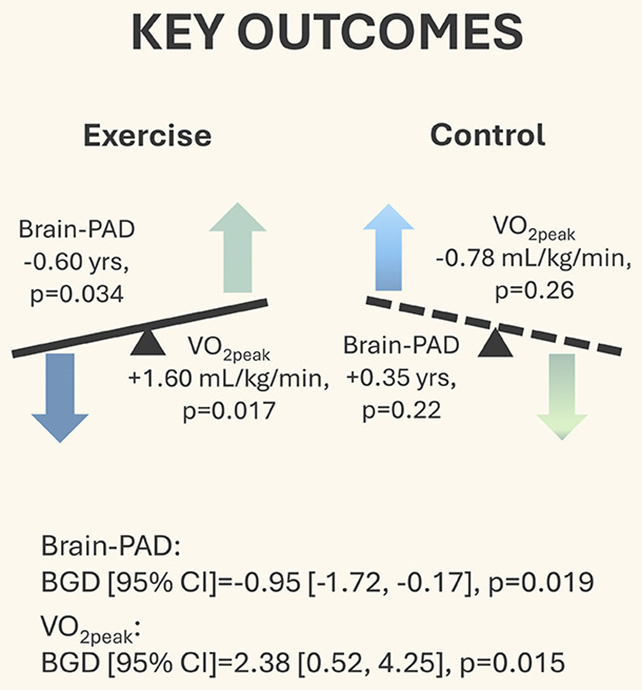

Based on a variety of biomarkers, MRI brain scans showed that those who followed the exercise regimen had brains that showed signs of being 0.6 years younger on average than their chronological age.

The participants who followed their usual routine, however, had brains that looked roughly 0.35 years older than their calendar age. This figure itself doesn't meet the threshold for statistical significance, the team says, but it means the difference between the groups is close to a year.

The next question is why exercise might keep the brain younger. Past studies have linked exercise to boosted brain function, but despite looking at several potential pathways – including cardiovascular fitness, blood pressure, and beneficial proteins – the researchers in the new study couldn't pin down the link in the chain between exercise and brain aging.

"That was a surprise," says Wan. "We expected improvements in fitness or blood pressure to account for the effect, but they didn't."

"Exercise may be acting through additional mechanisms we haven't captured yet, such as subtle changes in brain structure, inflammation, vascular health, or other molecular factors."

Those pathways can be investigated further in future studies, and the team is also keen to broaden the research out into larger and more diverse groups of people – perhaps those who are already considered at risk for cognitive decline.

Research has shown that problems with brain health later in life can be traced back to multiple factors that have an influence many years earlier, and it seems that exercise in middle age can have noticeable positive effects.

A youthful brain is more likely to ward off decline and disease, and has been linked to a longer life too. This adds to a growing pile of research into the key factors in the brain aging process.

"People often ask, 'is there anything I can do now to protect my brain later?'" says neuroscientist Kirk Erickson, from the AdventHealth Research Institute.

"Our findings support the idea that following current exercise guidelines – 150 minutes per week of moderate-to-vigorous aerobic activity – may help keep the brain biologically younger, even in midlife."

The research has been published in the Journal of Sport and Health Science.