Diamond isn't the first material that springs to mind when it comes to bending and stretching, but scientists have found a way to manipulate one of the hardest minerals on Earth - and it could lead to a slew of technological advances.

Not only is diamond hard, it's also very brittle. But the new study shows that on the very small scale, when diamond is in nano-needle form, the material can be bent and stretched by as much as 9 percent.

That's way above the standard 1 percent flexibility of the substance in bulk form.

Knowing that diamond nano-needles have this extra malleability could help in all kinds of fields, from delivering drugs into cancer cells to improving the design of data storage devices, according to the researchers.

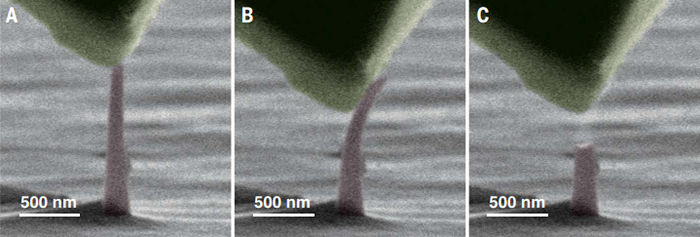

(MIT)

(MIT)

"It was very surprising to see the amount of elastic deformation the nanoscale diamond could sustain," says one of the team, Ming Dao from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

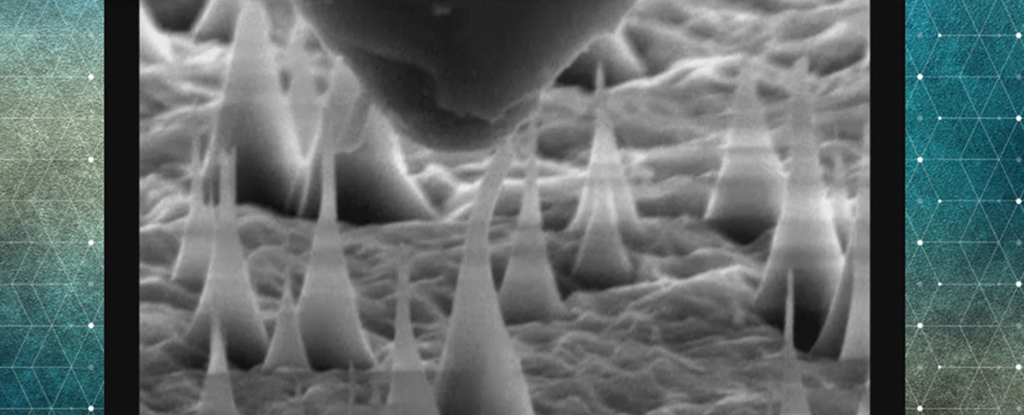

To achieve the feat, the scientists used a chemical vapour deposition process – essentially using chemical reactions to produce material coatings at very small scales, something which is used to make a lot of the components inside today's electronics.

The process produced tiny diamond needles a little over two micrometres in size, which were then pushed by a diamond tip and examined under an electron microscope.

You can think of them a little bit like the rubber tips on the underside of some toothbrushes, according to the team behind the study.

Using both experimental tests and a detailed computer model, the researchers were able to work out the exact breaking points of the diamond needles. And it was higher than expected.

Up to a tensile strain of 9 percent, the deformation completely reversed itself once the pressure was removed – if the needle was made of a single diamond crystal.

Nano-needles bending and fracturing. (MIT)

Nano-needles bending and fracturing. (MIT)

"We developed a unique nanomechanical approach to precisely control and quantify the ultralarge elastic strain distributed in the nano-diamond samples," says one of the team, Yang Lu from City University in Hong Kong.

Part of the reason the diamond nano-needles could flex like this was down to the lack of defects and relatively smooth surfaces at such a small size, noted the researchers.

Nano-needles bending and fracturing. (MIT)

Nano-needles bending and fracturing. (MIT)

The next step is to study in more detail how the properties of diamond start to change in this smaller form – why these nano-needles are more resistant to snapping, and how added pressure affects these properties. That should give us some clues about how best to use them in the future.

Uses for diamonds go way beyond expensive jewellery, and cover applications in biosensing and bioimaging equipment, drug delivery, next-generation hard drives, optomechanical devices and super-strong nanostructures.

For example: only last month scientists worked out how to create a diamond maser that could work at room temperature – a microwave version of a laser that could come in handy for medical scanners and security scans at airports.

Having a new type of diamond with extra flexibility, and different kinds of thermal, optical, magnetic, and electrical properties, could make the stuff even more useful.

"When elastic strains exceed 1 percent, significant material property changes are expected through quantum mechanical calculations," says Yonggang Huang from Northwestern University in Illinois, who wasn't involved in the study.

"With controlled elastic strains between 0 to 9 percent in diamond, we expect to see some surprising property changes."

The research has been published in Science.