Offering incredibly high temperatures, crushing pressure, and a thick mix of carbon dioxide and sulfuric acid, the atmosphere on Venus is deadly to human beings, several times over – but China has plans to penetrate this hostile environment and bring samples back.

The ambitious plans have been put together as a joint effort by the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), the China National Space Administration (CNSA), and the China Manned Space Engineering Office (CMSEO).

They were announced last year, with a tentative launch window of 2028 to 2035 mentioned. However, few details have been given about how the mission is going to work, or what it's designed to look for.

With a slide from the mission program recently shared on social media, the plans are back in the news. The slide shows some of the aims of the mission, which include looking for signs of life, determining how the planet evolved, and analyzing atmospheric cycles.

As inhospitable as Venus and its atmosphere are, recent research has suggested that microbial life could exist on the planet in some form. Being able to take samples straight from the source should be able to help us settle the debate that's been raging since that controversial paper.

The new slide also mentions taking a close look at another of the big mysteries of Venus: how its clouds can apparently absorb ultraviolet radiation, even though they shouldn't be able to. Several hypotheses have already been published exploring this question.

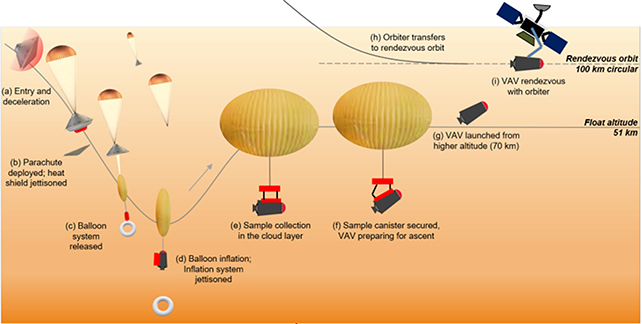

A minimum of two spacecraft will likely be needed too. One will stay in orbit around Venus, while another will dive down into the intensely stormy conditions in the atmosphere, picking up gases and particles.

We do have some clues about how this might work, as a mission into the atmosphere of Venus was previously proposed by a team from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) back in 2022, though ultimately not picked up by NASA.

In the MIT proposal, a Teflon-coated, corrosion-resistant balloon would've been given the job of carrying a collection canister through the clouds, before that canister was sent back up to orbit and returned to Earth.

The benefit of getting samples back to Earth is that we can carry out far more sophisticated tests in scientific labs than we're able to on Venus itself – but the gap of tens of millions of kilometers between the planets presents something of an issue.

We have actually landed on Venus before: probes sent by Russia spent a couple of hours taking photographs before disintegrating, back in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. However, those spacecraft never made it back.

Several successful flybys have also taken place, and data taken from these trips is going to be invaluable in figuring out what a Venus sample collection mission is going to have to cope with once it gets there.

Even if just a small sample of material could be returned, it would transform our understanding of Earth's sister planet.