Elemental carbon is extremely versatile, and scientists have long been able to create new carbon allotropes that make for super durable and multi-functioning materials - such as everyone's favourite material, graphene.

The 'carbon family' is one very resourceful family. But even with all these developments, carbyne remained elusive. In fact, it is the only form of carbon that has not been synthesised, even though researchers have been studying its properties for over 50 years.

The reason for this is that carbyne is extremely unstable. This one-dimensional carbon chain was first discovered in 1885 by Adolf von Baeyer, who even stated that carbyne would remain elusive, as its high reactivity would always lead to its immediate destruction.

Carbyne's mechanical properties are hypothesised to exceed all known materials. It's assumed to be twice as stiff as graphene, 40 times stiffer than diamond, and have greater tensile strength than any other carbon material. With these kinds of properties, no wonder we've been trying to find ways to stabilise it.

And now, an international team of researchers have now found a way to mass-produce carbyne.

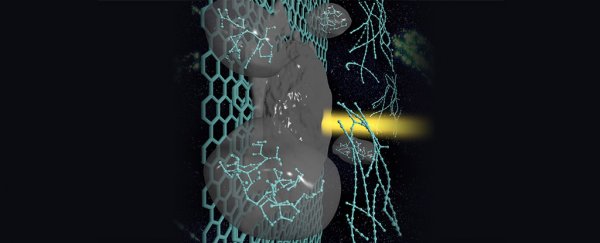

The team took two layers of graphene, pressed them together, and rolled them into thin, double-walled carbon nanotubes. The tubes were then wrapped around the atoms. These nanotubes protect the carbyne chains from meeting imminent doom.

Their research is published in the journal Nature Materials.

Before their discovery, the record-holding number of carbon atoms in one continuous chain was 100. Now, the record has been broken with an astounding 6,400 atoms utilizing this novel method – and the chain continues to be stable.

Also, carbyne's electrical properties increase with its chain length. This means that researchers will be able to experiment with the material more effectively with success from the nanotubes.

There is a huge wealth of possible applications using carbyne, and we're excited to see what kinds of devices will arise with the delivery of this 'miracle' material.

Image: Lei Shi/Faculty of Physics, University of Vienna

Image: Lei Shi/Faculty of Physics, University of ViennaThis article was originally published by Futurism. Read the original article.