Scientists have discovered evidence of the largest known undersea landslide along the Great Barrier Reef, finding the remnants of an ancient, massive slip measuring about 30 times the volume of Australia's famous rock formation, Uluru.

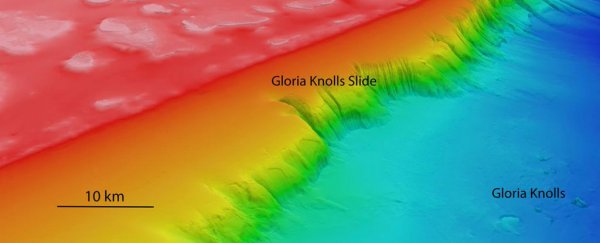

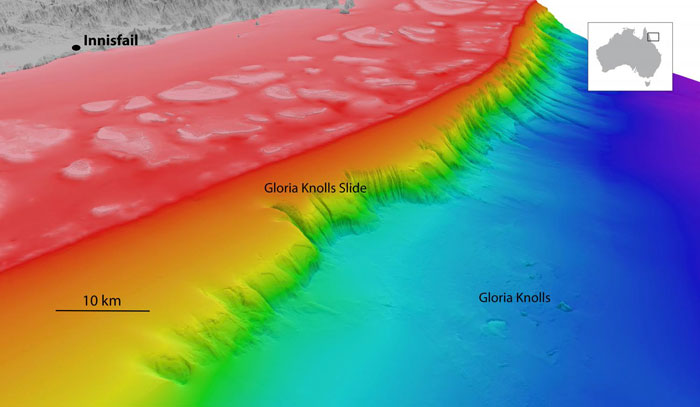

This ancient landslide complex – called the Gloria Knolls Slide – is what remains after a huge amount of sediment that once made up Australia's continental shelf broke off in a violent undersea collapse that took place more than 300,000 years ago.

A 'slide' like the Gloria Knolls Slide is the landmass that remains after a mass movement of material from a hill or cliff. While we tend to think of landslides as occuring on dry ground, they also happen in the sea.

Researchers led by Angel Puga-Bernabéu from the University of Granada in Spain found the landslide after discovering a debris field of large blocks on the ocean floor that had scattered up to 30 kilometres (18.6 miles) from the site of the collapse, coming to rest in an area called the Queensland Trough.

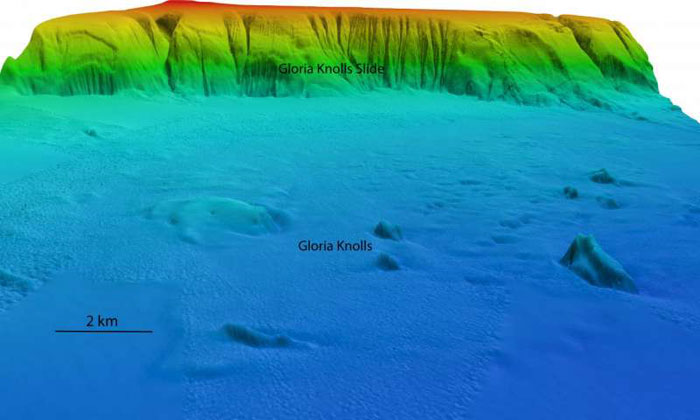

"We were amazed to discover this cluster of knolls while 3D multibeam mapping the deep Great Barrier Reef seafloor," says researcher Robin Beaman from James Cook University.

"In an area of the Queensland Trough that was supposed to be relatively flat were eight knolls, appearing like hills with some over 100 metres (328 feet) high and 3 kilometres (1.9 miles) long."

These knolls – along with more than 70 other smaller blocks – rest at depths as far down as 1,350 metres (4,429 feet), and were first discovered during ocean surveys in 2007. In the time since, the researchers have been busy trying to figure out where these massive rocks originated.

"It's taken quite a number of cruises since to actually find the smoking gun [that shows] where these blocks came from," Beaman told ABC News.

Subsequent mapping eventually led them to the Gloria Knolls Slide, which runs for 20 kilometres (12.4 miles) along the border of the Great Barrier Reef. While researchers had previously discovered other landslides in the area, this event was by far the largest.

When the shelf gave way, some 32 cubic kilometres (7.7 cubic miles) of sediment and rock tumbled down the slide and onto the ocean floor – and the effects of this massive displacement under the waves wouldn't have gone unnoticed on the water's surface.

According to the researchers' calculations, when the undersea collapse happened 300,000 years ago, it would have triggered a giant tsunami, yielding waves as high as 27 metres (88.6 feet).

Given that the Gloria Knolls Slide lies just 75 kilometres (46.6 miles) off the eastern coast of Australia, it's likely this event would have had a devastating impact on the Australian shoreline.

Fortunately, if a similar collapse were to happen today, the team says the effect might be not prove quite as dangerous for coastal communities – thanks to the existence of the coral reef itself.

"The impact of any resultant wave would likely be dampened significantly by the presence of the relatively modern, 9,000-year-old formation we call the Great Barrier Reef, but this remains to be assessed systematically," says one of the team, Jody Webster from the University of Sydney.

A sediment sample taken from one of the scattered knolls identified both living and fossil cold-water coral species on the block, which came as a shock to the researchers, given the extreme, inhospitable depth of 1,170 metres (3,838.6 feet).

"It's completely dark, it's quite cold, about 4 degrees Celsius (39.2 degrees Fahrenheit), and yet we have a habitat for cold water corals that are attached to rocks buried in the mud," Beaman told ABC News.

"When we brought a sample up there was a lot more marine life there than we ever anticipated, so that was a real surprise."

Dating of the oldest fossils in the sample indicated coral that was 302,000 years old, which indicates that the landslide occurred at least that long ago, but finding out more about this ancient event – and the marine life that existed in its aftermath – will require more research.

"We'd like to know more about the deep animals of the Great Barrier Reef because, yes, the shallow water corals are all very important, but we want to understand about the deep marine life too," Beaman said.

"This is an area that's really emerging."

The findings are reported in Marine Geology.