When we think about memory storage, we often think about the way we used to do it, by etching data onto a disc. But that's pretty outdated - these days, we use flash storage, which can be electrically erased and reprogrammed - just like the kind on your USB drive.

Although we've made great progress in shrinking these devices down, scientists are still struggling to get them below 10 nanometres per data cell.

But now an international team of researchers has taken things one step further and managed to store data on a single molecule.

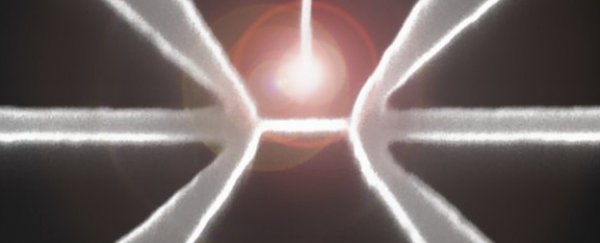

The entire flash storage device is actually three molecules big, and is made up of two molecules holding the electrons that store the data, and then a third that acts as a tiny cage. To put it into perspective - each side of the cage is only around one nanometre in length.

In this proof-of-concept experiment, the team used a tungsten molecule as the cage and selenium trioxide molecules to hold the electrons. Impressively, their set-up was stable at temperatures up to 600 degrees Celsius and managed to store the electrons for up to 336 hours (the longest amount of time they tested for) reliably. The results are published in Nature.

Of course, this research is still in the very early stages and it's going to be a long time before you're storing all your iPhone contacts onto caged molecules. The scientists, who are led by a team at the University of Glasgow in Scotland, now need to work on speeding the process up, and also making it more efficient - right now it requires large amounts of voltage compared to current devices.

As Adam Clark Estes writes for Gizmodo:

"Setting the device and writing data took tenths of seconds and milliseconds. To compete with existing flash storage devices, this molecular monster would need to get much faster."

However, based on their model, the researchers believe that they could get writing the memory onto the device down to picoseconds speeds.

"But the authors note that, by this point, the actual path the electrons take into the molecule will dictate performance, so they don't expect to see that sort of speed," John Timmer writes for ArsTechnica.

In the past, scientists have managed to make flash devices from single-atom-thick layers of graphene, but these sheets need to be stacked in order to work. This is the first time that a stand-alone, molecule-sized device has been used to create flash storage.

And although it's early days, it's a pretty exciting development in the constant race for smaller and faster technology.

Source: Gizmodo, ArsTechnica