Symptoms of depression in middle age could point towards the likelihood of dementia later in life, a new study shows, which could perhaps enable precautions and treatments to be put in place earlier.

Depression and dementia have been linked before, which is part of the reason for the new research, led by a team from University College London (UCL). In this study though, the researchers identified six specific symptoms that may act as warning flags.

"Our findings show that dementia risk is linked to a handful of depressive symptoms rather than depression as a whole," says epidemiological psychologist Philipp Frank.

"This symptom-level approach gives us a much clearer picture of who may be more vulnerable decades before dementia develops."

Related: The Cause of Alzheimer's May Be Coming From Within Your Mouth

The researchers analyzed data for 5,811 individuals taking part in a longitudinal study in the UK. Information on patients' mental health was collected between 1997 and 1999, when the participants were aged between 45 and 69 and all dementia free.

The health of these volunteers was then tracked for around two decades afterwards, on average. Dementia diagnoses recorded in UK health records and registries up to 2023 were used in the final results.

Over that time, 10.1 percent of the participants developed dementia – and those who reported five or more symptoms of depression in middle age were found to have a 27 percent higher risk.

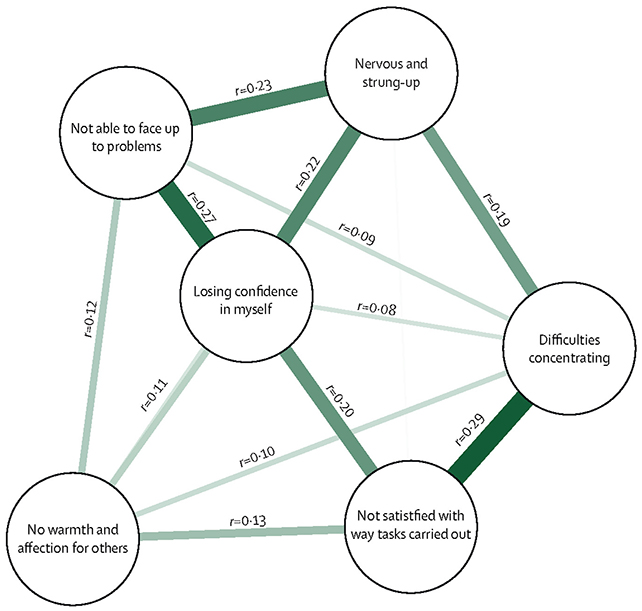

However, this risk increase was driven by six specific depressive symptoms, out of 30 assessed in total. Those six were losing confidence, difficulty coping with problems, not feeling affection for others, being nervous all the time, having difficulty concentrating, and not being satisfied with the way tasks are carried out.

The loss of self-confidence and not being able to deal with problems were particularly significant, with each increasing dementia risk by around 50 percent. Some symptoms, such as sleep problems and suicidal ideation, showed no long-term correlation with dementia diagnosis.

While the structure of the study doesn't show direct cause and effect, it suggests that certain elements of depression are associated with a higher chance of developing dementia – which may in turn inform research into why dementia takes hold of some brains but not others.

"Everyday symptoms that many people experience in midlife appear to carry important information about long-term brain health," says Frank. "Paying attention to these patterns could open new opportunities for early prevention."

We know that both depression and dementia are complex and multi-faceted, and different between individuals. That makes trying to establish connections between them challenging – but not impossible, as this study shows.

That said, there's no guarantee that these results apply universally. The team acknowledges that the research was conducted only in the UK, using relatively healthy civil servants. Dementia was found to be less common in participants in the longitudinal study, compared to the general UK population.

Related: Laughing Gas Can Offer Immediate Relief From Depression, Study Finds

More research is needed in more diverse cohorts, especially with dementia expected to become more prevalent as the growing global population gets older. But it could give scientists a place to start at least, and if a proportion of those cases can be prevented, it could make a huge difference.

"Depression doesn't have a single shape – symptoms vary widely and often overlap with anxiety," says epidemiologist Mika Kivimäki. "We found that these nuanced patterns can reveal who is at higher risk of developing neurological disorders."

"This brings us closer to more personalized and effective mental health treatments."

The research has been published in The Lancet Psychiatry.