New research shows that 'hacking' the communication channels between microbes in the mouth could boost levels of beneficial bacteria – a strategy that could potentially reduce the risk of tooth decay and improve oral hygiene.

Bacteria use a chemical-based messaging system called quorum sensing, which affects which types survive, thrive, and spread in different parts of the body – by altering gene expression.

A team from the University of Minnesota in the US has demonstrated how these signals operate and can be interrupted in the mouth, based on an analysis of lab-grown bacterial communities that form human dental plaque.

Related: Losing Your Teeth Could Be a Deadly Warning, Study Finds

"By disrupting the chemical signals bacteria use to communicate, one could manipulate the plaque community to remain or return to its health-associated stage," says biochemist Mikael Elias.

While we're still in the early stages of disrupting this bacterial 'chatter', the researchers found a way to 'turn off' the signals that usually encourage the growth of bacteria linked to gum disease (also known as periodontal disease).

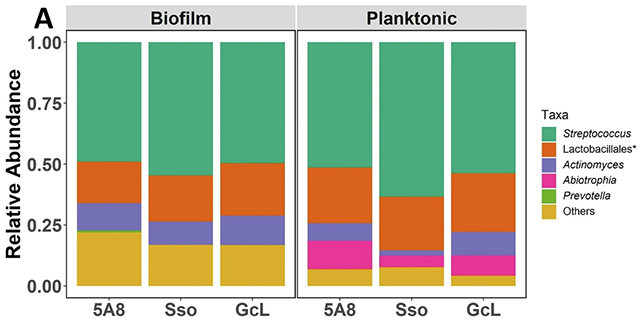

"Dental plaque develops in a sequence, much like a forest ecosystem," says Elias. "Pioneer species like Streptococcus and Actinomyces are the initial settlers in simple communities – they're generally harmless and associated with good oral health."

"Increasingly diverse late colonizers include the 'red complex' bacteria like Porphyromonas gingivalis, which are strongly linked to periodontal disease."

The researchers looked at N-Acyl homoserine lactones (AHLs), molecules used by some bacteria in the mouth for quorum sensing. They found that certain enzymes could block quorum sensing by inhibiting AHLs.

Crucially, this blocking process promoted the growth of healthier bacteria, rather than bacteria that contribute to dental plaque. While there's still a long way to go to fully understand how bacterial communication can be hijacked for our benefit, this study shows how it might be possible.

Another key finding was that meddling with AHL signaling had different effects on bacterial colonies grown under standard conditions (like those on the surfaces of teeth and gums) and under low-oxygen conditions (such as those in plaques and in the nooks and crevices of the mouth that don't receive much air).

Bacteria growing as biofilms were more sensitive to treatment than free-floating communities, which didn't change much.

While bacteria in oxygen-poor (anaerobic) environments don't produce AHL signals themselves, the researchers found, they can still sense signals from elsewhere. This further improves our understanding of how this bacterial communication system works.

"Quorum sensing may play very different roles above and below the gumline, which has major implications for how we approach treatment of periodontal diseases," says biochemist Rakesh Sikdar.

More research will be needed to confirm that the processes seen under these simplified lab conditions actually occur in the mouth, and the study didn't go as far as measuring the impact on gum disease or tooth cavities.

However, the new information is encouraging. We also know that the health of our teeth and gums is linked to brain, heart, and general health, and the researchers are hopeful that the approaches used here may help combat bacterial infections in other parts of the body.

"Understanding how bacterial communities communicate and organize themselves may ultimately give us new tools to prevent periodontal disease – not by waging war on all oral bacteria, but by strategically maintaining a healthy microbial balance," says Elias.

The research has been published in NPJ Biofilms and Microbiomes.